The Lexington Club:

Nate Allbee stood in a room surrounded by crying women and he realized that something was terribly wrong. They were dykes and lesbians and queer women of all races, ages, and backgrounds, who had gathered to mourn the passing of the Lexington Club. A bar that had — for almost 20 years — been the beating heart of San Francisco’s lesbian community. A place where generations of queer women met, organized, and shared in the communion of the dance floor. It had been their home, their church. Now it was closing its doors for good. So they had come — from all over the San Francisco Bay Area and all over the country — to pay their respects, to celebrate its memory, this place that had been their home, as well as mourn its passing. They laughed and sobbed and told stories about how this bar had changed their lives, until the Lexington Club’s ample hall could not contain them or their stories, and they spilled out into the street and the warm summer night.

There are certain cities around the world that have been places of sanctuary for queer people, none more so than San Francisco. Perched as it is, at the edge of the world and the end of the American frontier, it’s the last refuge for trailblazers and those who think differently. Nearby gold fields and tech booms have served as convenient excuses for those who needed to escape the small towns and farmsteads of their birth in order to be their authentic selves.

When Harvey Milk ran for office, he ran at least partially on the idea that the best thing any of us can do for our community is to come out of the closet and come to the city, where we would find a place for ourselves.

“And the young gay people in the Altoona, Pennsylvanias and the Richmond, Minnesotas who are coming out,” Milk once said. “The only thing they have to look forward to is hope. And you have to give them hope. Hope for a better world, hope for a better tomorrow, hope for a better place to come to if the pressures at home are too great.”

That vision of San Francisco as a city of queer sanctuary had attracted Lila Thirkield to the city in the early ’90s. There, when just 25 years old, Thirkield had been inspired to open the Lexington Club to serve a growing lesbian community in the city’s Mission District.

Above: Lila Thirkield, who opened the Lexington Club in 1997, poses with plaque memorializing the now-closed bar.

Nate Allbee was drawn to the city a decade later. A tall and handsome man with a broad smile and a booming voice, he moved to San Francisco in his 20s to work as a nightlife promoter before falling into political organizing when City Hall began passing restrictions on his chosen industry. And though Allbee was not a lesbian, he too found a home in the Lex, and its loss in 2015 sent him reeling. It wasn’t the first establishment to close that year. Other valued S.F. gay institutions had already sunk beneath the surface of the rising tide of hyper-gentrification, but the Lexington Club was one of the most respected and celebrated queer bars in the country, if not the world. “I was stunned. I realized if the Lex can close, no gay bar is safe,” said Allbee. “People kept asking ‘What can we do?’”

But in the end there was nothing to do; the last lesbian bar in San Francisco closed. The Lex was gone.

Legacy Business Registry:

The shuttering of the Lexington and other queer bars — including Esta Noche, a bar that had served San Francisco’s LGBT Latinx community for 33 years until it too closed to make room for gentrification — represented an incalculable loss to the queer community. In many ways, these bars served the same role in the LGBT rights movement as churches did for the African-American civil rights movement, acting as a safe place for queer people to congregate and share political ideas.

They were also vital to the economic health of San Francisco. Tourism has long been a leading industry in the city, and LGBT tourism makes up a significant portion. Esta Noche and the Lexington were economic drivers, part of what drew those tourists from all over the world. So Allbee began to look for ways to bulwark these spaces, integral to queer life, against S.F.’s ever soaring rents. (The city has some of the highest housing costs in the nation.) California state law forbids rent control for commercial properties, and the current structure of historic preservation only allows for the saving of tangible features like crown molding. It doesn’t protect the idea of places or the businesses inside of them.

The first step was to find a way to identify and catalog historic businesses being threatened by gentrification. To that end, Allbee met with Mike Bueller, executive director of San Francisco Heritage, who Allbee calls a “punk rock star of preservation.” Together with Supervisor David Campos they created the Legacy Business Registry — the first registry of its kind in the nation. Businesses that have served the community for at least three decades are nominated by the mayor and city supervisors. Those establishments are asked to go before San Francisco’s Historic Preservation Commission and Small Business Commission to make a case that they are important to the culture and history of their neighborhood. If both commissions approve them, then the business itself — not the building thay houses it — is officially recognized as a historic and cultural asset of the city of San Francisco. Perhaps most importantly, in addition to formal recognition, businesses added to the directory are also able to access a rent stabilization fund to help them weather the out-of-control S.F. real estate market.

But once you identify what’s historic and worth preserving, how do you then protect these businesses from a real estate market that has little incentive to preserve queer spaces? You have to take them out of that market system. “Not to sound Marxist,” says Allbee, “but if the capital-driven market is going to — by its very nature — close down queer spaces, then we have to operate outside of that market. So I started to look at models that do that.” The very clear and obvious model in San Francisco was co-ops.

San Francisco has a rich history of worker-owned cooperatives: from grocery stores to bakeries to the Lusty Lady (the first worker-owned and unionized strip club in the U.S., pictured above). Allbee started meeting with people from these co-ops to learn everything he could about how co-ops function. “If we had been ready we might have been able to save the Lexington. The next time one of these gay bars was going down, I was going to make sure that we were there to save it.” The opportunity to try was right around the corner.

The Stud:

More than a year after the closing of the Lexington Club, Allbee found himself in another room, in another bar in San Francisco, but this time there were no tears. He was at San Francisco’s oldest gay club, the Stud, a space every bit as sacred to the Bay Area’s queer performance and drag community as the Lex had been to queer women. All around him, many of the leading members of that community — drag queens, DJs, bartenders, party promoters, writers, musicians, burlesque dancers, and other practitioners of the “nightlife arts” — sat stone-faced as they listened to a story that was by now all too familiar. The building housing the Stud had been sold, the new owners were raising the rent significantly, and the Stud’s owner, Michael McElhaney, preferred to retire after 20 years of bar ownership rather than fight. He told those assembled that if anyone was interested in saving the Stud he would support them. If not the bar would be closing its doors.

Allbee looked around the room and saw “some of the smartest people that I’ve ever had the pleasure to know or work with. The real artistic core of the S.F. LGBT nightlife community was in that room.” Among them, VivvyAnne ForeverMore, hostess of Club Some Thing, the Stud’s long-running and beloved Friday night drag show. Upon hearing the news, she was devastated.

“Not only has it been my nightlife home for the last seven years, but a lot of the people I work with came up at the Stud. It has a lot of history for me personally. And culturally, the history of The Stud is very rich, and I can’t imagine it not being there, not just for what it is, but what it represents.”

Immediately after the meeting, Allbee grabbed her and said, “Vivvy, I’ve been preparing for this. I think we can save The Stud.” Between the two of them they pulled together a group of 15 people (which later expanded to 18) from across the queer community, and they then spent the next six months in an intensive co-op boot camp: learning what they are, how they work, and tailoring co-op structures for a bar. If the team pulled it off, The Stud would be the first worker-owned nightclub in the United States.

The newly formed Stud Collective reached out to the community for support and was able to raise the equity to purchase the bar. The collective negotiated with the landlord to both decrease the rent and extend the lease two years. And it has breathed new life into one of San Francisco’s most beloved LGBT institutions. New parties, new promotions and the workers — everyone behind the bar, security, the person checking IDs at the door, and many of the drag queens on stage are now the proud owners of one of the most storied gay bars in the country.

At the stroke of midnight on December 31, 2016, it became official. The collective had been notified the day before, and as Vivvy and fellow co-op member Honey Mahogany (of RuPaul’s Drag Race season 5 fame) took the stage to ring in the New Year there was an air of disbelief. Many of those assembled had been at the Lex on her final night a year and a half earlier, and when the clock struck 12 a similar scene played out — with drinking and tears and stories about how a bar had changed their lives — but this time was different. This time they had won.

Above: San Francisco’s Queer Land-Use Activists (from left): Honey Mahogany, Compton’s District Coalition; Oscar Pineda, the Stud Collective; Aria Sa’id, The Compton’s District Coalition; Mica Sigourney, the Stud Collective; Rachel Ryan, the Leather District Coalition; Nate Allbee, the Legacy Business Foundation

Legacy Business Foundation:

To build on that success and help queer communities beyond San Francisco preserve their culture and history, Allbee has started a nonprofit, the Legacy Business Foundation. “What we are trying to do right now is get ready to spring into action when the next bars are closing and the bars after that, and take what we’ve learned about how to start these worker-owned co-ops — how to negotiate with landlords, how to make sure that the city is providing the support that these legacy businesses deserve—and start saving these bars and restaurants on a citywide scale.”

LGBT culture and history, Allbee believes, is under assault. Not from blind economic forces, but from the machinations of an industry that often sees LGBT spaces as a barrier to their bottom line — realtors associations and for-profit developers. “In some ways there is a concerted and orchestrated effort to work against minority neighborhoods and business districts,” says Allbee. “To realtors and developers minority businesses are often seen as blight. A gay bar or a Latino venue where Latin music is being played or a bar that’s a historic place for African-Americans to congregate: They think they bring down the value of a neighborhood, just by their existence.”

“We’re really in a war with developers and realtors on how to define our historic neighborhoods. We want to keep them queer and realtors want to turn them into whatever will make the most money.” Allbee points to the realtors’ maps used to sell property in San Francisco. “They’ve completely removed the Castro and even Chinatown from their maps. It’s like they’re hoping that people will just forget we were ever there.”

“We need to be legislatively protecting our historic neighborhoods — and that’s dense, complicated work. We want to be a resource to help other queer communities in other cities do that work. And as a national and worldwide community, we need to be investing our money into helping queer non-profits acquire land in our neighborhoods.”

That work is essential, Albee argues, because “queer people don’t just want community, we need community. If you stay in the suburbs, if you stay in cities that are predominantly straight, sure you’ll find tolerance — maybe acceptance — but you’ll always be that gay sidekick who dies first in the horror movie. If you find your community, you can actually be the star.”

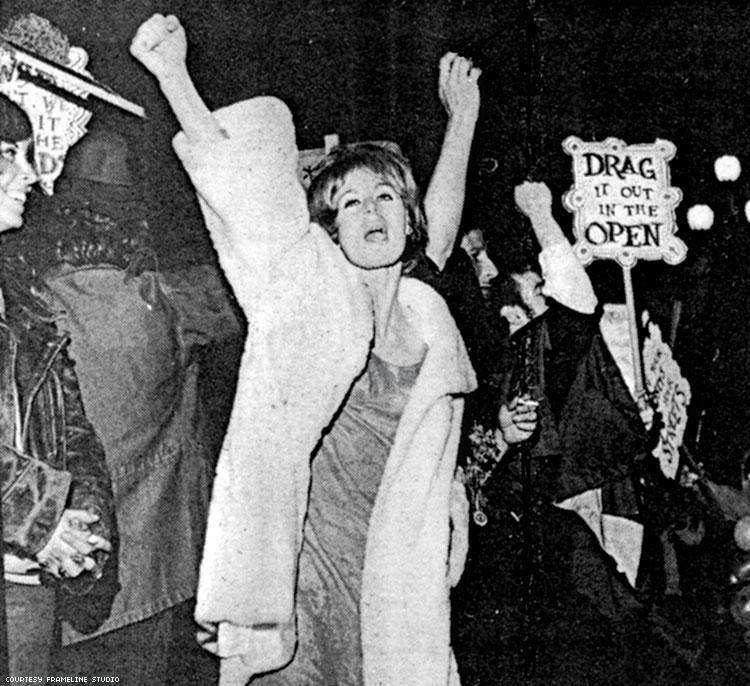

Above: Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria, an Emmy Award-winning documentary of the collective resistance by queer and trans people in San Francisco (especially trans women of color), which occurred three years before Stonewall.

Compton’s:

As the Stud Collective was making history as the first worker-owned bar in America, the Obama administration was making some history of its own. LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History, a publication of the National Park Foundation, argues that LGBT historical spaces need to be preserved and lists some of the prime real estate in need of protection. Penned by leading representatives of the LGBT community, the study includes a chapter by renown transgender historian Susan Stryker, who co-directed the 2005 documentary Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria. The number 1 site on that list of historic LGBT places was the Stonewall Inn, which President Obama later designated a national monument. Number 2? Compton’s.

Compton’s Cafeteria was an all-night diner at the corner of Turk and Taylor in S.F.’s Tenderloin. It was one of the few places where trans women, and particularly trans women of color, could gather publicly. In the summer of ’66 a hostile staff member called the police, and an ensuing riot poured into the street and lasted two days. This was one of the very first LGBT civil rights uprisings in the U.S. — though the queer history of the Tenderloin neighborhood goes all the way back to the Gold Rush.

With the release of the report, the federal government had — for the first time — recognized the importance of preserving LGBT history. Reading the expansive 1,000-page document, Mahogany and Allbee realized that a number of these spaces significant to the birth of the trans rights movement were in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, and they were almost all being threatened by development.

Mahogany and Allbee approached Janetta Johnson, head of the Transgender Gender Variant and Intersex Justice Project, Aria Sa’id of the St. James Infirmary, and Brian Basinger from Q Foundation, Inc., with a unique idea: Using San Francisco’s arcane land use laws to create the first legally recognized transgender neighborhood in the country.

With the support of San Francisco Supervisor Jane Kim the group created the Compton’s Transgender, Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual District, centered on the old cafeteria. The area making up Compton’s TLGB District has the densest number of historical resources for the trans community anywhere in the country. The legislation creating it officially recognizes this history as an asset to the city and makes protecting it a priority. But Allbee says it doesn’t go far enough.

“It’s all about land. We need to make sure that transgender women in the Compton’s District are gaining control of that land,” says Allbee. “The businesses need to belong to them, the buildings that house the businesses need to belong to them, the apartments where they live need to belong to them, empty lots to build future housing need to belong to them. We need to make sure the trans district is a space run for trans people by trans people. That’s the only way this community will ever be truly protected.”