Continuing the Dream: Reflections on 38 years of collecting SF LGBTQ history

On March 16, the GLBT Historical Society marks 38 years since our founding. To celebrate the occasion, we are thrilled to provide an interview with Greg Pennington, a founding member of the Society. To learn more about our history, visit glbthistory.org/timeline.

Was there a specific event that spurred you and the other founders to organize in 1985?

I moved to San Francisco in March 1977 as part of the wave of gay men that came here in the late 70’s. I heard about the election of Harvey Milk and George Moscone and wanted to live somewhere where I could truly be myself.

Just two months after I arrived, Anita Bryant helped overturn the gay rights ordinance in Miami and the San Francisco LGBTQ community reacted very strongly. The headline in the SF Chronicle was “5,000 angry gays march through San Francisco.” The marches went on for 5 nights and although I did not go to the first one, on the second night I heard the marchers going through my neighborhood on lower Nob Hill and I joined them for the next four nights.

This event was a catalyst for me, and I began collecting gay periodicals from all over the country. I was collecting as much information as I could about everything that was going on in the gay community. I wanted to preserve our history.

I met with Harvey Milk in his City Hall Office in July 1978, about creating an archive for our community. He was very supportive of young people like me fulfilling their dreams. He told me that he would help me make it happen. He issued a press release for a community meeting that would be held on August 28, 1978. Unfortunately, Jack Lira, Harvey’s lover at the time, hanged himself near the time of the meeting and it never happened.

In 1983 I met Bill Camilo, through a mutual friend and Bill invited me to a party at Scott Smith’s house (Harvey Milk’s lover at the time of his assassination) for a gathering with the people that wanted to form a gay library. At that meeting I met Willie Walker. Walker, Camilo, and I later met and formed the S.F. Gay and Lesbian Periodical Archives. Walker and I merged our substantial collections and kept them at his house. Camilo would later drop out of our project. We included the word lesbian in our title because Walker was beginning to amass numerous lesbian publications, such as The Ladder.

Walker and I met in my living room in the summer of 1984 and discussed his plan to create a historical society. I went with him to a meeting of the SF Lesbian & Gay History Project on September 5, 1984, to propose the idea and get their support and help to create the organization. They unanimously agreed to join us.

Walker, Eric Garber, and I were among about 10 people that met several times in the fall of 1984 to form the organization. We made some initial decisions about things until we realized we would have to start over because we needed to have future members of the organization involved in the decisions. Then we changed our focus to preparing what decisions would need to be made at a public meeting to create a Historical Society. We organized the public meeting that was held on March 16th, 1985, at the S.F. Public Library.

What was the atmosphere like at the first meeting?

There was excitement in the air as a very broad spectrum of community members answered the call to create an organization. The meeting was very well attended by over 50 people. Many of us were meeting each other for the first time. Walker’s letter to invite members of more than 160 community organizations and more than 100 individuals was wildly successful.

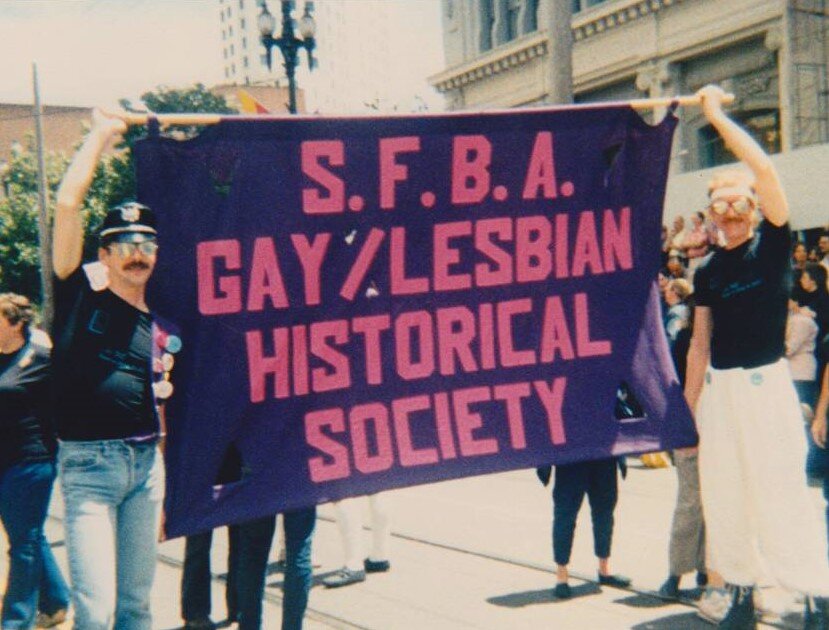

I think we did a good job of organizing the meeting presentations, topics of discussion and decision points. The issue that took the longest to resolve was the name. After at least a half hour on that subject we chose the San Francisco Bay Area Gay and Lesbian Historical Society. Fortunately, years later we made improvements to the name as it was just too long. We did fit that name on our early banner, buttons, and t-shirts though.

Tell us about the other founders: what were their specific interests?

Willie Walker was a labor archivist in Butte, Montana before he moved to San Francisco in 1981. He was a nurse and served on the AIDS ward at San Francisco General Hospital. Walker, like me was a collector of periodicals and ephemera. He would go through community businesses collecting every free piece of paper he could get his hands on. His apartment, like mine was full of ephemera and printed matter. His apartment served as the first archives for the organization after we were founded.

Walker was always focused on doing things the right way to create a professional organization. He was our first archivist, and he got his master’s degree in library science in 1988 from U.C. Berkeley. Walker passed away from liver cancer in 2004 at age 55. It is very sad to me that he never got to see what the organization has become.

Eric Garber was one of our founding members, first Board members and served as our first newsletter editor. Eric was involved, like Walker, in the S.F. Lesbian and Gay History Project. Eric was interested in gay sci-fi and co-authored Uranian Worlds. Eric did research on all the gay bars, names, and locations in San Francisco. His research is in the collection of the archives. Unfortunately, AIDS took Eric before he could publish his bar research. Eric was once a roommate of Cleve Jones and a friend of Harvey Milk.

Were there any specific initiatives or areas of focus that the founders felt that the organization should prioritize in its infancy?

Walker and I both wanted to create an archive, but we realized that we would need a broadly focused organization to create interest and bring in the people and support we would need. The Society would create an archive but would also do historical programming, publish a newsletter, create a museum, and other activities to promote LGBTQ history. We had monthly programs in our first few years on a broad variety of topics of interest to the diverse elements of our community. We published the first issue of our newsletter very quickly after our formation.

The organization formed at the height of the AIDS holocaust in San Francisco when more than 20,000 LGBTQ people died. Walker and I were very concerned when families came to San Francisco for their gay sons that had passed away and threw away all of their stuff. We felt an urgent need to get as much of it as possible. We were losing a great number of people and a lot of our history.

We were also very keenly aware of what had happened under the Nazis in Berlin to the Magnus Hirschfield collection. At the time it was one of the finest collections of gay manuscripts and materials in the world. The Nazis destroyed all of it. Because of that we decided our collections must be under community control and not controlled by any government agency. We did not ever want to lose our collections because of a shift of political winds. We also did not want the government to censor, suppress, ban, or destroy our sexually explicit materials. Our sexuality is an important part of our history.

As the society approaches its 40th anniversary and we reflect on its impact, what are one or two things you are particularly proud of from this legacy?

I am very proud to have been part of the creation of this successful organization for the protection, preservation, and promotion of LGBTQ history. Any creator wants to be able to step out of the way and allow his idea and creation to flourish. I greatly appreciate the incredible volunteers, Board Members and staff that have continued our dream.

I am proud that we achieved our original goal of creating an archive that is a major research center for movie makers, authors, researchers, and community members. It is so important for younger generations to be able to learn about the history of our communities.

I am most proud of the diversity we have achieved in the organization. We still have further to go as there is always room for improvement. In the beginning we were mostly white cis men and we later had good parity of men and women but our consistent long-term focus on the importance of diversity paid off in the long run. Over time we reflected more of the racial and ethnic diversity and fortunately, we also expanded to include the transgender community. The LGBTQ community is the most diverse community on Earth, and we must reflect that.

What are your hopes for the society in the future?

I want to see a vibrant internationally acclaimed LGBTQ history museum in San Francisco that is a model for the world, and a tourist attraction that keeps LGBTQ people visiting San Francisco. It needs to be big enough to have space for us to reflect the vast diversity of the LGBTQ communities. I hope that our world-renowned archive collections can be co-located with the museum. I hope that younger generations will be excited to learn about our history and about all of the diverse elements of our communities.

Greg Pennington was a founder of the GLBT Historical Society. Originally from Wichita, KS, Greg moved to San Francisco from Los Angeles in 1977 at age 20. Greg retired after a 30 year career with the United States Environmental Protection Agency in 2014. Greg served as the first LGBT Program Manager in the nation in the EPA San Francisco regional office starting in 1998. Greg spent 20% of his work time on issues of concern to the LGBT employees. LGBTQ history has always been one of Greg’s most important hobbies.

To celebrate the Pride season, the GLBT Historical Society has four free museum days scheduled for June! These free days are made possible by the generosity of the following sponsors: the Bob Ross Foundation, Castro LGBTQ Cultural District and Big Run Studios, Inc., as part of Doors Open California. Online tickets are not available; just come to the museum during normal business hours and you will be welcome.

To celebrate the Pride season, the GLBT Historical Society has four free museum days scheduled for June! These free days are made possible by the generosity of the following sponsors: the Bob Ross Foundation, Castro LGBTQ Cultural District and Big Run Studios, Inc., as part of Doors Open California. Online tickets are not available; just come to the museum during normal business hours and you will be welcome.