New research helps explain why lesbians report more orgasms than straight women

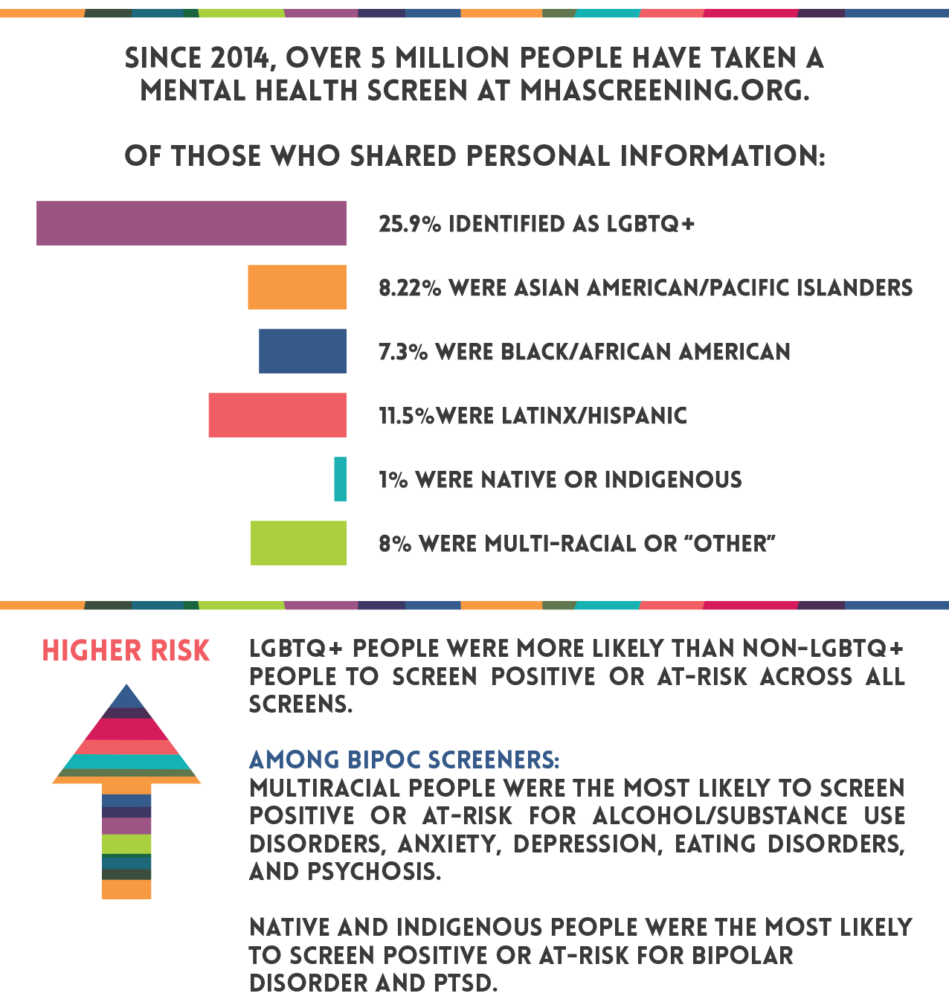

Research over the last decade has found that lesbians have more orgasms than straight women, but questions remained as to why.

A new study published this month in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science found that these differences when it comes to pleasure could be in part due to sexual scripts — or what people expect to happen during sex based on what they’ve seen in movies, television or even pornography. Cisgender women’s expectations for those sexual scripts and for orgasms can vary based on the gender of their partner, the study found.

Past research has found that men have more orgasms than women, creating what researchers call the orgasm gap. Previous studies have also found that lesbians have orgasms at rates similar to men, which shows that there’s “nothing inherently biological” about the orgasm gap, according to Grace Wetzel, one of the study’s authors and a psychology doctoral candidate at Rutgers University. Wetzel said she wanted to look into the “sexual context” missing from that research, or the other psychological and social factors affecting differences in orgasm rates.

“We wanted to look into why that disparity between lesbian and heterosexual women exists so that we could get a better understanding of why the orgasm gap exists in general,” she said.

Wetzel and two other researchers designed two online studies — one of heterosexual women and lesbians and another of bisexual women. The first study asked a mixed group of 476 heterosexual women and lesbians about the importance of orgasms and their expectations about climaxing during sex. It found that lesbians reported more clitoral stimulation in their sexual encounters, higher orgasm expectations, greater orgasm pursuit and having more orgasms than heterosexual women. However, orgasms were equally important to heterosexual women as they were to lesbians.

In the second study of 482 bisexual participants, the researchers asked the women similar questions about their expectations of orgasms and how strongly they would pursue them in a hypothetical sexual encounter with either a man or a woman.

That study found that bisexual women had the same orgasm pursuit and importance regardless of partner gender in the hypothetical scenario, but those partnered with women in those cases had higher expectations for clitoral stimulation and orgasms than those hypothetically partnered with men. This means that partner gender, through varying sexual scripts, is indirectly associated with greater orgasm pursuit, the study found.

The average sexual script, or what people expect to happen during sex based on TV, culture and more, between a man and a woman, according to the study, includes foreplay, then vaginal intercourse, from which the man orgasms, and then sex ends.

“This heterosexual script prioritizes the man’s orgasm, as intercourse alone is associated with the lowest orgasm frequency for women,” the study said. Women who have sex with women are more likely to engage in nonpenetrative acts and don’t adhere as much to any sexual script based on gender, researchers added.

“What we should take away from this research is that when women are having sex with men, in general, they’re typically not experiencing enough clitoral stimulation to facilitate an equal opportunity for orgasm,” Wetzel said, adding that the findings should encourage heterosexual couples to improve communication during sex.

Wetzel noted that the study shouldn’t lead couples to feel pressure, because other research has shown that such pressure will make orgasms less likely and less enjoyable. Rather, couples, regardless of sexuality and gender, could “work to make their sexual encounters more pleasurable in general by including those sex acts that are most likely to result in orgasm for their partner.”

The study is limited in part by its correlational design, Wetzel said. As a result, the researchers don’t know all of the factors that affect the difference in orgasm frequency between lesbians and heterosexual women. Some of the other factors behind that difference could be that women feel more comfortable communicating with other women versus men about what they need to experience orgasm. That’s where the second study is helpful, she said, because the only variation between the hypothetical sexual encounters bisexual women were asked about was the gender of their partner.

“That doesn’t mean there still can’t be other factors at play as well, but because of that experiment in the second study, we feel more confident saying that these sexual scripts are differing based on partner gender,” she said.

Incia Rashid-Dawdy, a counselor with the Expansive Group, a therapy practice based in New York City and Chicago, said the study shows how people in heteronormative relationships have been socially conditioned to see orgasm through vaginal penetration as a “goal,” while people in queer relationships aren’t going into sex with the same gendered expectations.

“When we’re talking about queer relationships, lesbian relationships, we’re talking about how, in order for them to be able to understand how to make each other feel good, they need to talk about it,” she said. “This is a reminder that there’s no one way to have sex.”