Queer Youth Negatively Affected by Anti-LGBTQ+ Laws, Debates: Trevor Project Poll

Debates over LGBTQ+ rights are having a negative effect on the lives of young people in the community, according to a new poll.

“An overwhelming majority of LGBTQ youth have been negatively impacted by recent debates and laws around anti-LGBTQ policies and that many have also experienced victimization as a result,” says a press release on the poll, conducted for the Trevor Project by Morning Consult between October 23 and November 2 and released this week.

The poll included 716 LGBTQ+ youth ages 13–24 around the U.S. It assessed emotional responses to anti-LGBTQ+ policies as well as which other social issues often give LGBTQ youth stress and anxiety. It came in a year in which more than 220 anti-LGBTQ+ bills were introduced around the nation, most of them targeting transgender youth; many more are being introduced in 2023 — 150 across 23 states in the first two weeks of the year, the Trevor Project reports.

Among the key findings: Eighty-six percent of transgender and nonbinary youth say recent debates about state laws restricting the rights of transgender people have negatively impacted their mental health. A majority of those trans youth (55 percent) said it impacted their mental health “very negatively.” Seventy-one percent of LGBTQ+ youth overall say state laws restricting the rights of LGBTQ+ young people have negatively impacted their mental health.

Seventy-one percent of LGBTQ+ youth — including 82 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth — say that threats of violence against LGBTQ+ spaces, such as community centers, Pride events, drag shows, or medical providers that serve transgender people, often give them stress or anxiety. Nearly half (48 percent) of those LGBTQ+ youth say it gives them stress or anxiety “very often.”

As a result of anti-LGBTQ+ policies and debates in the last year, trans and nonbinary youth say they have had a range of harmful experiences, including cyberbullying or online harassment (45 percent); stopping speaking to a family member (42 percent); not feeling safe going to the doctor or hospital (29 percent); having a friend stop speaking to them (29 percent); bullying at school (24 percent); their school removing Pride flags or other LGBTQ-friendly symbols (15 percent); and physical assault (10 percent).

Among all LGBTQ+ youth, one in three report cyberbullying or online harassment, one in four say they stopped speaking to a family member or relative, and one in five say they experienced bullying.

Regarding policies that will bar doctors from providing gender-affirming medical care to trans and nonbinary youth, 74 percent of these young people say they feel angry, 59 percent feel stressed, 56 percent feel sad, 48 percent feel hopeless, 47 percent feel scared, 46 percent feel helpless, and 45 percent feel nervous.

Policies that prevent trans youth from playing on the sports teams aligned with their gender identity make 64 percent of trans and nonbinary youth feel angry, 44 percent feel sad, 39 percent feel stressed, and 30 percent feel hopeless, according to the poll.

There were also bad reactions to anti-LGBTQ+ school policies, given debates around respecting students’ identities and pronouns, censoring LGBTQ-inclusive curricula, and banning books. New policies that require schools to tell a student’s parent or guardian if they request to use a different name/pronoun or if they identify as LGBTQ+ at school make 67 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth feel angry, 54 percent feel stressed, 51 percent feel scared, 46 percent feel nervous, and 43 percent feel sad.

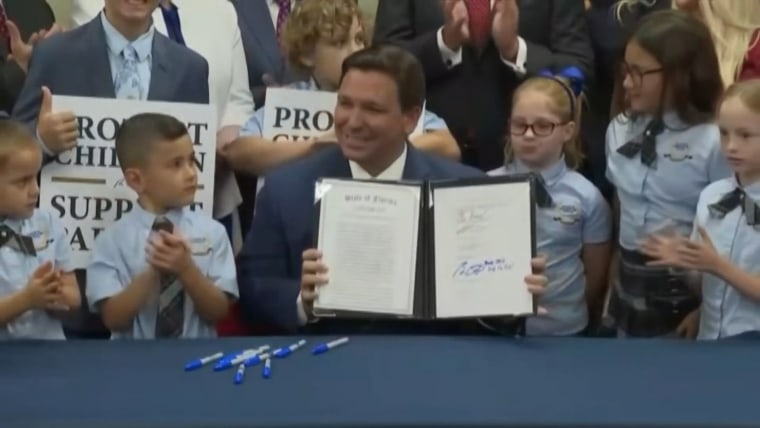

Fifty-eight percent of LGBTQ+ youth, including 71 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth, feel angry about new policies that bar teachers from discussing LGBTQ+ topics in the classroom. Among trans youth, 59 percent feel sad and 41 percent feel stressed.

Sixty-six percent of LGBTQ+ youth, including 80 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth, feel angry about policies that will ban LGBTQ-inclusive books from school libraries. Nearly half of LGBTQ+ youth, including 54 percent of trans youth, also felt sad about these book bans.

Black LGBTQ+ youth sampled reported disproportionately higher rates of racism, police brutality, doing poorly in school, and gun violence giving them stress or anxiety “very often” compared to white LGBTQ+ youth. Trans and nonbinary youth polled reported disproportionately higher rates of transphobia, losing their health care, anti-LGBTQ+ hate crimes, and threats of violence in LGBTQ+ spaces giving them stress or anxiety “very often” compared to cisgender LGBQ+ youth.

“Right now, we are witnessing the highest number on record of anti-LGBTQ bills introduced this early in any legislative session. We must consider the negative toll of these ugly public debates on youth mental health and well-being. LGBTQ young people are watching, and internalizing the anti-LGBTQ messages they see in the media and from their elected officials. And so are those that would do our community harm,” Kasey Suffredini, vice president of advocacy and government affairs at the Trevor Project, said in the release.

Suffredini added: “The Trevor Project is proud to see that more than two-thirds of LGBTQ youth, including 81 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth, have seen, read, or heard about our work to fight back against anti-LGBTQ bills. We are prepared for the fight ahead and will not stop advocating for a safer, more accepting world for all.”