Literary Lesbian Desire

When author and editor Lise Weil wrote about lesbian desire for the first time, it was in response to Sex and Other Sacred Games, a novel by Kim Chernin and Renate Stendhal. Weil reviewed the book for Trivia: A Journal of Ideas, of which she was then editor. The year was 1991. Now some 28 years later, both Weil and Stendhal have published memoirs centered on lesbian desire: Weil’s In Search of Pure Lust recalls the 70s and 80s in the U.S., a time when lesbian desire was the throbbing center of an entire culture and a movement. Stendhal’s memoir Kiss Me Again, Paris evokes the same women’s culture at its height in Paris, when the entire city was suffused with lesbian eros. Their memoirs are “sister books” from across the Atlantic, both celebrating, albeit with different cultural inflections, a historical era Stendhal considers the lost “Golden Age” for women.

Lise Weil: The most obvious affinity between our books is that they’re centered in the same culture/movement but in different countries. And for both of us there was a poignancy in writing about that culture/movement because it has all but disappeared, is on its way to becoming a forgotten piece of our history.

Renate Stendhal: I had been looking for years for a book that would recapture that first discovery of women’s condition as the “second sex” (Beauvoir) and as “colonized people” (as French feminists put it). That awakening to everything: a new world vision, a new language, desire and agency, in short, that golden age of women in the late 60s and 70s to the mid-80s. I found only one book that remembered, step-by-step, women’s new thinking and it was a French book: Cathy Bernheim’s Perturbation, My Soeur. And now there is your memoir, In Search of Pure Lust, which does just that for American feminism, focusing both on politics and the very personal aspects of desire and the way each informed the other.

Weil: It was a time of profound awakening on so many levels–and above all it was our bodies waking up, our bodies wanting pleasure and wholeness. It was an eroticawakening of the first order. Your book is full of erotic awakenings!

Stendhal: No kidding. For me, desire had always been there in the form of unfulfilled yearning and pining and crushes for women (and girls when I was a girl). Those sweet grapes, always just out of reach. But then suddenly overnight everything was within reach. The old concepts exploded–that’s what you describe so well: the new words and concepts giving permission to rebel against all the rules, restrictions, gender barriers and limitations that corseted women. I focused my memoir on the high point of these freedoms in Paris, when women’s empowerment seemed to be a given. We had successfully invaded Freud’s “unknown continent.” We had discovered, entered, and occupied this territory body and soul–or, as you might say, body and thought.

Weil: Well yes, because one of the things we began to understand was that our bodies needed to enter thought; Adrienne Rich at the end of Of Woman Born wrote about “learning to think through the body.” This gave rise to vision. What we were able to see we saw because we were women inhabiting our bodies in a way that had not done since possibly Sappho’s time.

Stendhal: What extraordinary daring it took to overcome our “feminine” conditioning! I was a girly-girl, all smiles (when there was nothing to smile about) and unable to say no. The famous “sisterhood is powerful,” which seems all but forgotten now, made me bold and free. I came to envision and experience my body as a boy-girl’s, as androgynous–which was everyone’s ideal in Paris at that time. We were all crossing gender boundaries.

Can you talk more about your vision in terms of love and sex and body?

Weil: Well that’s not where my vision went. It was loving women and being in bed with women that gave rise to the vision, but then the vision went out—to, well, everything that is looming over us with such menace now, the poisoning of the earth, militarism, racism, nuclearism, hatred of and violence against women, separation from nature. We saw it back then and we saw that it was all connected. We were the original intersectional thinkers, the original deconstructionists.

Stendhal: Yes, that’s what we were all doing, day and night: deconstructing the history of men and the herstory of women. The endless destruction of a male-dominated world. This was political and philosophical work and it was also, and for me majorly, cultural work.

Weil: That’s why it felt so important for me, in my memoir, to document our lives, our culture: the bookstores, the conferences, the study groups, the concerts, the book fairs, the bars. To document it in as much detail as possible–and not to leave out the bitter squabbles and conflicts, both personal and collective. It felt especially important to do this because young lesbians and queer women today generally have no idea about our lives, and the tremendously rich–if flawed–culture that emerged from them.

Stendhal: … And the incredible writing! The discovery of Virginia Woolf and Gertrude Stein as our woman-loving ancestresses; the discovery of all the silenced, conveniently forgotten artists–from Artemisia Gentileschi to Meret Oppenheim and the women of Surrealism. From matriarchal temple art in Asia to Louise Bourgeois’s gender-defying contemporary sculptures. From African dance to Pina Bausch’s radical dance theater. This was the exuberant new world I lived and breathed in in Paris.

Weil: We had similar ideas about what would bring down the system. Yes to activism yes to cultural upheaval—but more profoundly what we believed could change everything from the bottom up (it could be I’m just speaking for myself here) was loving women… In a world in which woman hatred was endemic and foundational this was the most subversive the most life-affirming response.

Stendhal: I talk about the huge erotic wave that had every woman in Paris in its grip. The euphoria is what I wanted to remember most of all in my memoir–this wild hope of woman-loving.

Weil: The irony in this, and it’s an irony that deeply informs my book, is that when it came to loving women I didn’t have a clue. Oh I knew how to make love to women, to want want want women… but when it came to loving in a way that was sustainable…to “loving with deep recognition” (which is what I decided early on feminism had to be about) I had everything to learn and in fact had a lot of things stacked against me. My search for love was riddled with relationship errors.

I believe your book traces a similar arc, no? Not the novice part so much but a growing understanding that the culture of seduction you were part of was getting in the way of that kind of love, which requires that the masks come off…

Stendhal: Yes. Adventures, affairs, being outrageous, daring to play: this part of liberation began to reveal its limitations. And of course it became my personal dilemma. There still was my romantic yearning for the soulmate, or twin-soul, for deep love and recognition. I would say and you might agree, longing for a kind of love that was essentially anti-patriarchal.

Weil: Yes, even if we weren’t entirely able to embody it.

Stendhal: On the other hand, the culture of seduction, as you put it, seemed a necessary part of liberating our repressed women’s sexuality. Something important was achieved in taking this freedom, even taking it too far. We were the avant-garde of what today is the polyamorous and transgender edge.

And… the patriarchs went after us for it with a vengeance. Everywhere in Europe, the money faucets were turned off for women. The whole formidable backlash was launched. I was frankly shocked to see the sexual liberation of my generation become the next generation’s raunch culture, Girls Gone Wild. Lesbian love degraded into girls tongue-kissing for their boyfriends’ cell phones. From the moment the backlash started and the term “feminist” was turned into a hostile, “lesbian manhating” label, our revolution has been silenced, denied, bought, co-opted, and perverted. It has become the biggest taboo of our new millennium to name the direct connection we drew–or the first time ever–between woman-hatred and destruction of nature and the world. But the enormity of the backlash is a measure of the enormity of our achievements.

Weil: There you go, Renate! Connect that with good old lesbian rage. But honestly, it’s something all of us need to connect to now, because it’s not just women’s lives or lesbian lives—it’s all life on earth that’s being held hostage. The vision we had in those decades was alas incredibly prescient. It’s as if we had a direct window into now; what we feared and raged against back then has come to fruition in bone-chilling ways. That’s one of the reasons why the worlds we are writing about in these books matter so much, why it feels so important that they not be forgotten.

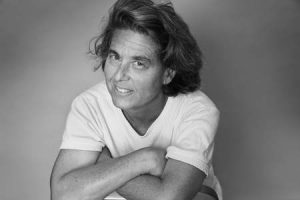

Lise Weil was editor of Trivia: A Journal of Ideas and its online relaunch Trivia: Voices of Feminism. Her memoir In Search of Pure Lust was published in June with She Writes Press (U.S.) and Inanna Press (Canada). She is founding editor of Dark Matter: Women Witnessing and teaches in the Goddard Graduate Institute. Born in Chicago, she has lived in Montreal since 1990.

Renate Stendhal, Ph.D. is a German-born, Paris-educated writer, writing coach, and critic. Among her publications is the award-winning photo-biography Gertrude Stein: In Words and Pictures. Her memoir Kiss Me Again, Parisreceived two awards and was a Lambda Literary finalist in 2018. She has translated major American feminists into German. Her cultural reviews are here.