Why are gays so terrible at intergenerational friendships?

Let me just start with a question. How many friends outside of your generation do you have? I mean honest-to-god friends. In my friend group, as large and fungible as that can be in the District and in the age of social media, it’s sort of me and a few other Gen Xers, and then just loads of Millennials. They do look to me to pass down some knowledge, but it’s mainly to do with the ins and outs of mortgages and things like that.

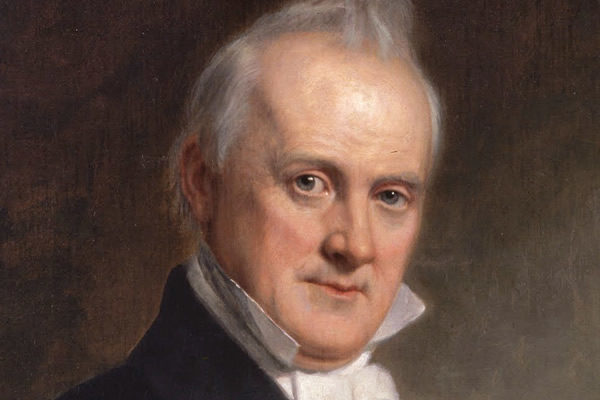

But is it me? Or are gays just really, really terrible at having intergenerational friends? It’s striking. I’ve recently developed a friendship with — let’s call him — Bill. He’s almost 80. Maybe it’s the historian in me, but I just love the stories. But more on that later. For now, to ask another question, just why are gays bad at having friends removed from their respective generations?

On social media this week I posted an obituary from a Houston paper dating from 1978. It was obviously from a gay man. You can tell from the coded language, “long time resident of this city despite stays on the West Coast.” And if that didn’t give it away, it ended with this rather heartbreaking language, “his parents requested that his friends not attend the memorial services!” Bill told me these sorts of obituaries — terribly vague but also cruelly pointed — were quite common in the dark days of AIDS. And this is succinctly why I think gays are so bad at having intergenerational friends, we’ve simply lost an entire generation of elders. And what was exactly lost with that generation is far more than can be enumerated in this column.

Back to Bill’s stories for a second. There is a real value in oral histories, the telling and passing down of shared experiences make our culture certainly more valuable and rich, at the very least far more interesting. And again, this is nothing new, as cultures across the globe seek to capture personal stories and first-hand viewpoints of history unfolding. But it’s not just the story itself that’s important. It’s also the perspective and opinions. These remain nuanced between generations. Again, that’s really not saying anything new. But these varied opinions and outlooks, if not shared and debated risk isolating gay men into rigid and unchanging views crafted in echo chambers.

Also, gays place a large premium on youth. And this, again, is nothing new, nor particularly gay. We just like what we like. But as Bill told me, he’s rather annoyed that any interest he expresses in a younger man is automatically filed under lecherous behavior. Let me just deal with this right here: We all, no matter the age, display to varying degrees lecherous behavior. Just get us a little dehydrated, a little tipsy, and throw us on the sand of Poodle Beach and watch the unwanted flirting unfold. So. But still we have to do better than mistaking anyone displaying interested in us as a simple sexual advance. That seems rather juvenile.

With contact between our generations low, we are in danger of passing down a culture to future queer Americans that might seem a little lopsided and even a bit, well, shallow. But what’s to be done? I’ve commented in past columns on how we’re failing older LGBTQ Americans, especially in the District. To remedy this, we should use what I call the Chicago model and what is being done at the Center on Halsted, the city’s LGBTQ community center. The Center offers numerous programs geared to the city’s LGBTQ senior population. But one that sticks out is a sort of a buddy program, pairing seniors, even those in care facilities, with younger friends. This would certainly help us here in the District better care for our LGBTQ seniors, and would also of course help with the bridging of our considerable generational divide. So perhaps we could reproduce this here in the District.

For now, I’ll continue to buddy up and enjoy my time with Bill.