An Egyptian tomb contains the first gay love story recorded in history

The visual of men embracing has sparked outrage throughout history, across land and sea. Wherever evidence of homosexuality has been found in any culture, controversy—and often fatal danger—soon followed. Despite this, gay men worldwide have continually chosen to risk their lives for each other.

But there’s evidence to suggest that gayness might once have been revered, at least enough to inspire a tomb fit for Ancient Egyptian royalty.

On November 12, 1964, Chief Inspector of Lower Egypt Mounir Basta led an expedition into the depths of a recently excavated burial shaft within the necropolis. Accompanied by diligent workmen, he descended into history, relying solely on the flickering glow of a kerosene lamp to illuminate their path.

Pack your bags, we’re going on an adventure

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for the best LGBTQ+ travel guides, stories, and more.

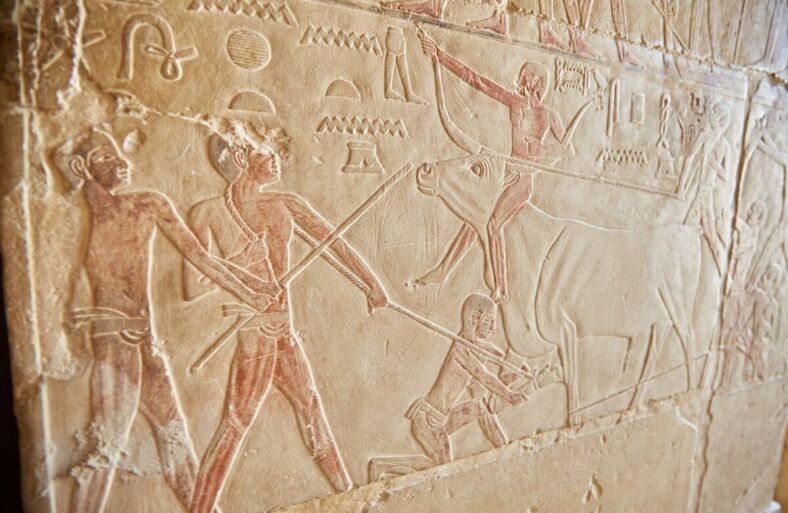

Many scholars, epistemologists, and archeologists believe they discovered the first documented depiction of a gay couple inside the 5th Dynasty tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep.

The entrance to the tomb is inscribed with the words: “JOINED IN LIFE AND JOINED IN DEATH.” Inside rest the royal manicurists Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, described in hieroglyphics as “royal confidants” to King Nyuserre Ini, a relationship reminiscent of the bonds many people share with their manicurists today. As personal groomers to the pharaoh, they were highly respected and among the fortunate few privileged to touch and cultivate a close relationship with him.

But what shocked the archeological world is the question mark hovering over their connection. Why were they sharing a tomb in such a romantic way?

The Legacy Project reported one thing as certain: “Two men of equal social standing being buried together in the same tomb – in spite of the fact that they were undoubtedly married to women – was unique.”

Award-winning scholar Raven Todd Da Silva vlogged about the discovery, urging the importance of independent thinking when looking for clues about the past.

“We’re all too aware of queer erasure in history,” said Da Silva. “There were so many gay couples in history that all these older historians described as ‘close friends’ or ‘roommates,’ especially for women.”

There were panels portraying their families, but their respective wives and children figures were featured almost as extras and never in an intimate manner. Regardless, some scholars argued their presence refuted any potential notion that Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep could be lovers. They speculated they could’ve been twins.

A queer Egyptology student at the University of Liverpool, Tamar Atkinson, argued that the “overall issue with these arguments is that they are set too heavily within the contemporary ideas of today. To dismiss the possibility entirely of same-sex desire being the case here may give in to the heteronormativity of many modern social attitudes.”

Egyptian culture heavily emphasized kinship and procreation for the next lineage. As part of the pharaoh’s inner circle, it was most likely expected – if not demanded – of them to follow suit in tradition.

French archaeologist Nadine Sherpion studied intimate portraits of heterosexual husbands and wives in tombs in Egypt’s fourth, fifth, and sixth dynasties to determine the iconographic trends and rules followed to portray a conjugal relationship.

In other words, she became an expert in discerning who was boning and concluded that the intimate poses shared between Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep could have been used in a hieroglyphic Grindr.

Most famously, the image of the men touching noses was the most intimate pose allowed by canonical Egyptian art. Beyond affection, Khnumhotep is uniquely depicted in activities reserved for women in Old Kingdom art, such as smelling a lotus.

If they were indeed lovers, perhaps the most telling aspect of their culture would be the tomb’s significance—it is considered one of the largest and most beautiful in the necropolis. This suggests that the pharaoh accepted them and held them and their relationship in high esteem despite the rarity of their iconography.

The gay tomb would make King Nyuserre Ini the first recorded LGBTQ+ ally.

Still, the tug-of-war between whether they were lovers or brothers continues to be debated decades later, of course, the queer community championing the historical visibility.

A professor of ancient Egyptian art at NYU recently suggested they could’ve been conjoined twins.

Da Silva added that this theory could be supported by the fact ancient Egyptians “seem to celebrate people who were different and viewed them as auspicious…and attested to the creator God’s ability to create things in whichever form He pleased.”

It is an ideology that sounds like gay rights from whichever angle, but the professor’s conjoined theory still doesn’t explain the romantic vibes.

Everyone’s free to come to their own interpretations. But the possibility of gayness being put on a royal pedestal could be a glimmer of hope that love and acceptance happened before judgment and hatred.

Through that lens, society could undoubtedly benefit by revisiting the old ways.