What does ‘Sapphic’ mean? An ancient term is having a modern moment

When people look at images captured by Ty Busey, the photographer says she wants them to know that the pictures and films were captured by a queer woman. Drawing on Renaissance paintings as inspiration, Busey poses her subjects, who are LGBTQ women and nonbinary people, with halos and textured backgrounds in lounging postures. She describes her artistic eye in one word: “Sapphic.”

The term derives from Sappho, a lyrical poet who lived in ancient Greece and created verses about pursuing women lovers that were rich in sensuality and nostalgia — and even libertine at times.

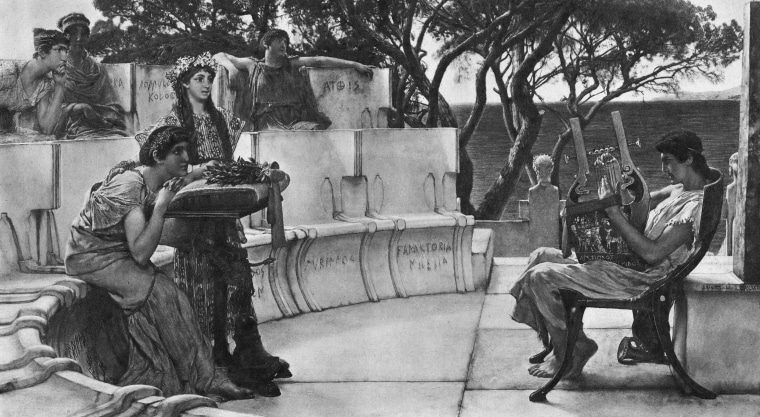

The style of Busey’s work is a fitting way to rectify its namesake’s historical legacy. In the hundreds of years after her death around 570 B.C.E., Sappho was often portrayed in art as heterosexual when her own poetry said otherwise.

When asked what she hopes viewers take away from her visuals, Busey said, “I want the person watching the video to be like, ‘Yes, this is what it feels like to be with a woman.’”

Busey, a Maryland resident who has identified as a lesbian since she was a teenager, first learned about the label “Sapphic” on TikTok in 2021. In the years since she’s embraced the term, it has abounded, appearing on social media meme pages, as a literary genre, as a descriptor for events in brick and mortar spaces and even as a noun for self-identification.

Over two-and-a-half millennia removed from its namesake, the term Sapphic does not have a precise definition that’s agreed upon by all of those who currently embrace it. However, its current use is generally as an umbrella term for lesbians, bisexuals, pansexuals and other women-loving women, and for transgender and nonbinary people who may not identify as women themselves but align with this spectrum of attraction and community.

While Sapphic may evoke ancient images of romance, it has a lesser-known political undercurrent: The poet Sappho resisted tyranny in her own era by the military general Pittacus, making her a potent queer symbol during a tenuous time for LGBTQ rights.

A rebirth on the internet

Describing herself as “chronically online,” Tyler Mead, 28, said she learned about the term Sapphic “funnily enough, actually, on the internet.”

As a singer, songwriter and producer under the moniker STORYBOARDS, she came across queer artists like Fletcher using the term.

“It got me intrigued, and I was like, ‘What does this term mean? What does this mean to them? And, what could it also mean for me?’ Because it’s been a bit of a journey for me of coming out in multiple layers,” Mead said.

In 2018, Mead came out as pansexual, then in 2020 as a trans woman. For the past year, she’s identified as a lesbian and as Sapphic, which she said captures a philosophy of “softness” in her approach to romance and dating.

“An interesting part of being a trans woman who is Sapphic is that, even before I started transitioning, I always knew that I was attracted to women … but not in a straight way,” Mead, who lives in Los Angeles, said.

The expansiveness of the term, she explained, is a strong draw, adding that she knows people who are trans masculine that use it.

A songwriter since middle school, Mead not only considers her music Sapphic but sums up her entire “energy” on the bio section of her TikTok profile as: “Sapphic fairy.”

The word “Sappho” appears to have first emerged digitally in 1987 on an early iteration of an email list, according to Avery Dame-Griff, curator of the Queer Digital History Project.

The Greek poet, it seems, was the namesake of an English language mailing list for LGBTQ women during a time when email would have only been accessible to those in academic or computer-related fields, according to Dame-Griff.

A name like Sappho, he explained, would have signaled that the mailing list was for queer women without using a term like “gay” or “lesbian,” which would have drawn unwanted attention.

Since 2004, the first year for which Google Trends provides search data, the term “Sapphic” peaked in December 2005 before steadily declining for the next 15 years. Since 2020, however, it has been on a steady upward trajectory.

Perhaps nowhere is the term currently more prominent than social media, where Sappho-themed meme accounts — Sappho Was Here, Suffering Sappho Memesand Sapphic Sandwich, just to name a few — have amassed tens of thousands of followers on Instagram. And, on TikTok, a wildly popular social media platform among those in the 18-29 demo, the term has been hashtagged over 340,000 times.

Some of those hashtags lead to 26-year-old New Yorker Nina Haines. During the pandemic, Haines said, she was craving queer community. Unable to see LGBTQ friends in person because of Covid, she started posting about Sapphic literature on TikTok in an effort to find connection.

Then, in 2021, Haines founded Sapph-Lit, a book club that today boasts 8,200 members from over 60 countries, with members who identify as queer women and nonbinary people. Her book picks have included modern romances, like Casey McQuiston’s “I Kissed Shara Wheeler,” and classics like Audre Lorde’s “Zami: A New Spelling of My Name.”

“At the end of the day, we really want to prioritize Sapphic literature, because Sapphics have been historically rendered invisible throughout history,” she said.

For Haines, who has a tattoo of Sappho on her arm, the term Sapphic “captures the women-loving-women experience” in a way that is “rooted in history” and that signals “that we have always been here.”

A historical legacy

Hailing from the Greek island of Lesbos and living from roughly 630 B.C.E. to 570 B.C.E., what is known of Sappho’s life comes from surviving fragments of her poetry and what was written about her by other ancients, according to Page duBois, the author of 1995’s “Sappho Is Burning” and a professor of classics and comparative literature at the University of California, San Diego.

Sappho’s queer legacy, duBois added, emerges from an expression of romantic and sexual desire toward women in her poems, often with a tint of nostalgia.

“They are really lovely and project that kind of world of voluptuous, flower filled, scented eros [desire] directed toward women,” duBois said.

But a passive “pink, romantic Valentine” she was not. “An aggressive pursuer of her lover,” Sappho described intimate memories of a far away, beloved woman, according to duBois.

“She talks about anointing her with beautiful ointments and putting garlands on her, and satisfying each other on soft beds,” duBois said of Fragment 94 of Sappho’s poetry.

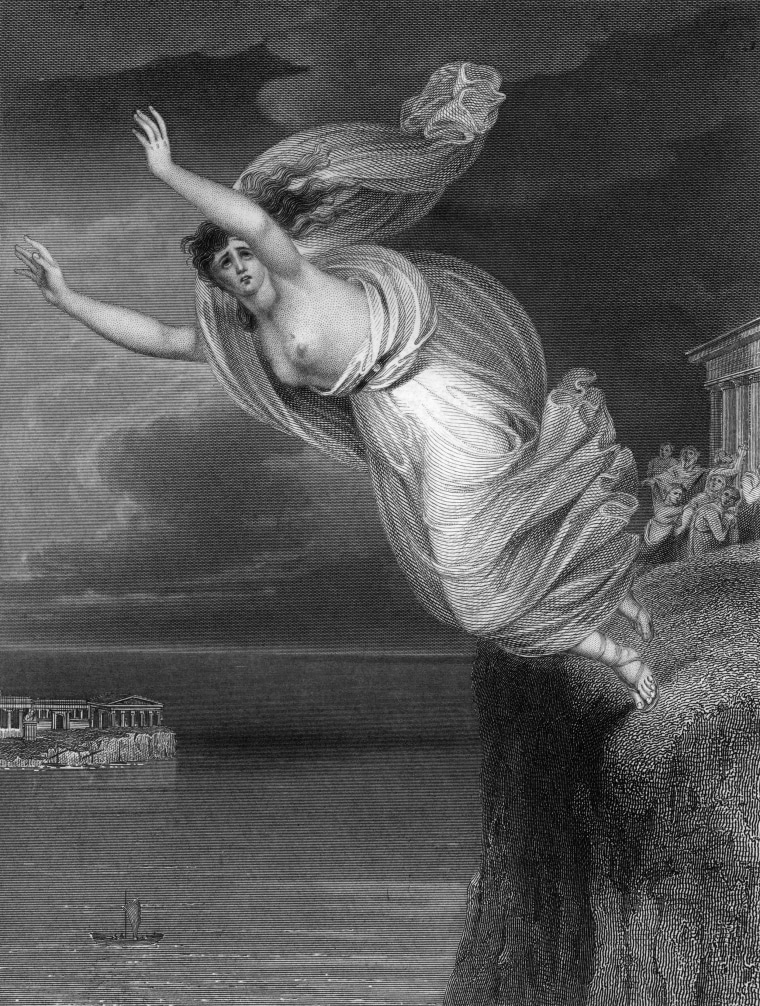

There are contradictory interpretations that Sappho was a schoolteacher, an aristocrat or a hetaira (a sex worker who operated like a courtesan or geisha), and that she was perhaps enslaved. In the Middle Ages and Victorian periods, she was presented as heterosexual in art, portrayed as a forlorn woman who threw herself off a cliff after she was rejected by a ferryman she loved.

Finding a new generation

For the past 100 years, an ever-evolving lexicon — and a debate about the best terms to use — has been a consistent feature of LGBTQ culture.

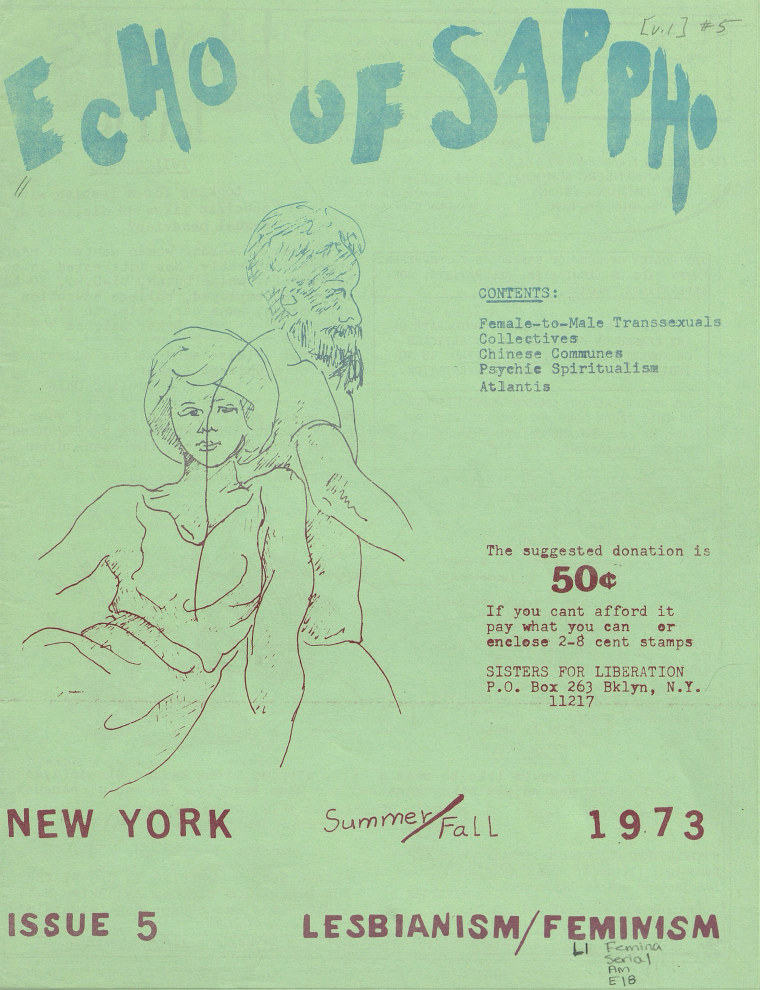

As far back as the 1920s, there are examples of “Sapphic” being used to advertise sexual entertainment, like sex shows, performed by women for a male audience. The term Sapphic can also be found in 1930s tabloid headlines, and several lesbian publications in the ‘70s and ‘80s incorporated the word Sapphoin their names.

It became more common for women to identify as a “lesbian” in the 1960s, though there were earlier exceptions, according to Cookie Woolner, author of “The Famous Lady Lovers: Black Women and Queer Desire Before Stonewall.”

Of course, butch, femme, dyke, stud and a host of other terms have been embraced by queer women, each shaped by the communities that created them and the social movements of their time.

“Maybe in some ways, the terms are changing because it’s about a break from a past generation,” said Woolner, an associate professor of history at the University of Memphis.

Though Woolner and others have noted that there are those who eschew certain terms or identifiers, for one reason or another. Some LGBTQ women, for example, don’t identify with “Sapphic” due to a perceived chasteness and the ancient aura.

For the past three years, Busey has organized a “Sapphic picnic” outside of Washington, D.C. For this year, Busey chose the theme “For the Gods,” an ode to Greek gods and goddesses and conducted a photo shoot to match.

“There’s something about those ancient photos and the way that they’re all falling on each other — I really love them so much,” she said. “I just want to recapture it specifically with women, especially if I could put a Black woman in there.”

More than 2,500 years after Sappho walked the earth, champions of the term Sapphic see the parallels between finding their own power and the erasure and subsequent embrace of the lyrical poet’s queer identity.

“I see her as this reclamation,” Haines said of Sappho. “As this statement of, ‘No, I actually mean the words that I say, and don’t twist them.’”