LGBTQ+ people are facing a mental health crisis. Sharice Davids is ready to fight for them.

Davids is currently fighting to win her fourth term this November — a tough battle, as her district’s demographics have changed to become less Democratic-leaning, and Republican opponents are lining up to challenge her. But she has also been fighting another very important battle: the fight for increased access to mental health care.

Davids has co-sponsored bipartisan legislation to fund mental health programs in local clinics, schools, and law enforcement centers, as well as a bipartisan bill to help people recovering from substance abuse reenter the workforce. She has also supported dozens of bills to bring down the costs of health care and prescription drugs and introduced the Pride in Mental Health Act — legislation that would improve data collection and resources for at-risk queer youth.

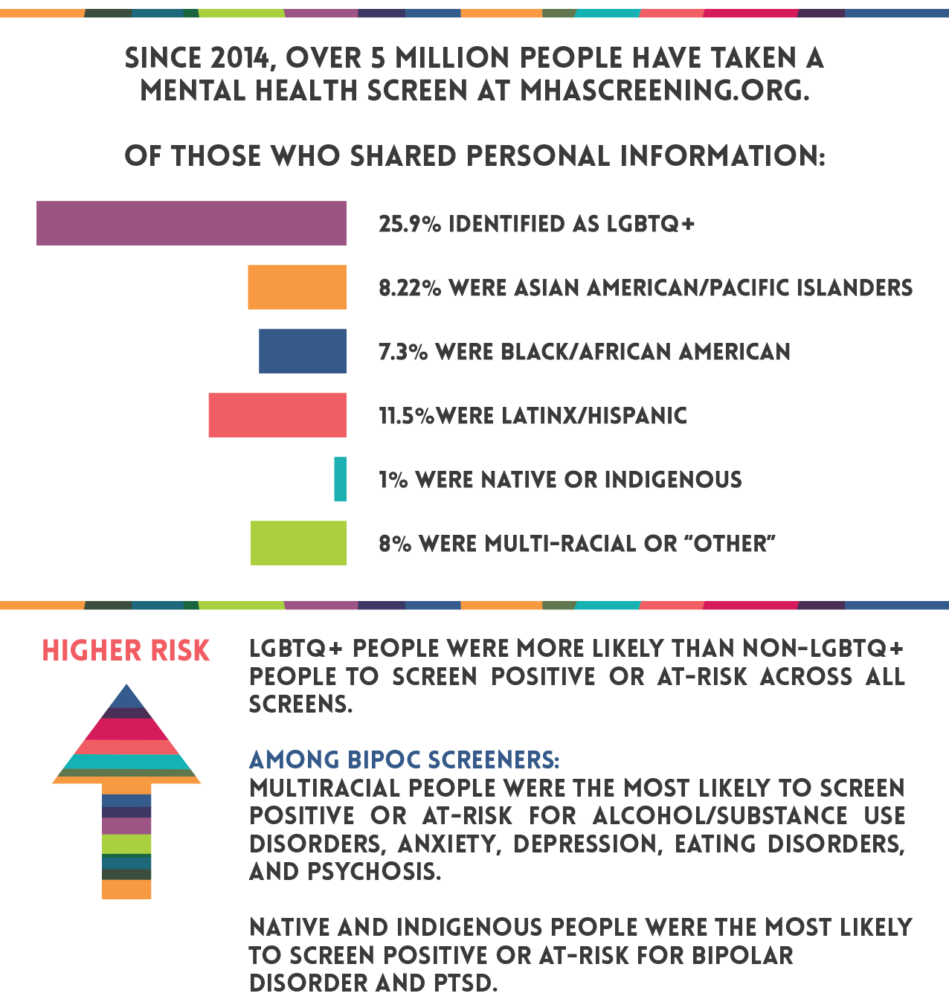

For Davids, mental health strikes an especially personal chord since she’s part of two distinct groups with disproportionately high rates of suicide: Native Americans and young LGBTQ+ people. Native Americans die from suicide at higher rates than any other racial or ethnic group, according to a 2022 reportfrom the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Another recent CDC study found that LGBTQ+ young people are over four times more likely to attempt suicide than their cisgender and heterosexual peers.

But this issue cuts across political, geographic, and generational lines, she says. If anything, Americans’ mental health worsened during the isolation, fear, and uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic — over half of adults with a mental illnesscan neither access nor afford mental health care.

Davids believes increasing access to mental health care isn’t merely “putting a Band-Aid on a broken arm.” Rather, she sees such access as an integral part of improving people’s overall emotional well-being.

“I think it’s like an all-of the-above approach, where we do need to be thinking about the most severe and sometimes acute issues happening around mental health or mental illness,” Davids says, “but we also need to be doing that long-term work that helps prevent things like bullying, helps prevent things like young people who are in the foster care system not having anyone around who understands, who has never gotten the training to understand what they’re going through as part of the LGBTQ+ community.”

“If what we’re doing over time is helping people understand how to cope, how to recognize the impacts of trauma, or help people interact with people who are experiencing those things,” she continues, “then I wouldn’t call that a Band-Aid. I would call it the necessary work for keeping people healthy and safe.”

Because many Americans have loved ones who have struggled with mental health, she’ll often watch her conservative colleagues’ committee hearings or press conferences to listen for an opening to reach across the aisle and engage them on this issue.

“There are folks who care about youth mental health and emotional well-being in a way that it probably just doesn’t cross their mind to think about the LGBTQ+ impact,” she says. Some of her conservative colleagues are “often surprised” when they find out about the aforementioned CDC statistics. These discussions can sometimes lead to larger conversations about LGBTQ+ civil rights.

Praising David’s bill to improve data collection on the mental health of queer youth, Melanie Willingham-Jaggers, executive director of the LGBTQ+ student advocacy organization GLSEN, said, “Being excluded, erased, and further stigmatized — by discriminatory policies, peers, and by adults who should protect young people — harms LGBTQI+ youth’s mental health and overall well-being.”

Related:

Davids says, “A lot of times, [my conservative colleagues] might not be aware of how often discriminatory practices [against LGBTQ+ people] are allowed under the law. It’s not right, and it’s not fair, and it doesn’t align with the values that, as Americans, we want to see and that we’re all constantly striving for,” she says.

The mental health disparities facing the LGBTQ+ community are just one part of the institutionalized discrimination experienced by queer people.

Studies suggest that when queer people have the same legal protections as their cisgender and heterosexual peers, their mental health improves, alleviating the anxiety and depression that otherwise accompany worries about discrimination. When Davids points out to colleagues that people can be rejected from a jurybased on their sexual orientation or denied housing based on their gender identity, she notes that she’s not trying to give “special rights” to people based on their unique identities — she’s just trying to make sure that all individuals are afforded the same rights, protections, and responsibilities as other citizens under the law.

Questioning the 2024 election’s long-term impact

Since arriving in Congress, Davids has noticed Republicans increasingly targeting LGBTQ+ rights amid their attacks on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Last year, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and members of the far-right Freedom Caucus demanded the removal of LGBTQ+-inclusive DEI policies from 12 appropriation bills to effectively fund all U.S. government agencies. She and other Republicans claimed that policies are “woke,” are anti-American, waste taxpayer money, and make the nation less safe.

Similar criticisms have especially accelerated now that it’s an election year.

“There’s a shift, we’ve seen it, and we’re also seeing it in state legislatures that there’s a ‘two steps forward, one step back,’ ” she says. “There’s a ‘one step back’ happening in quite a few places on a number of different types of issues.”

“We have responsibilities to the people who come after us, but also to the people who came before us.”Rep. Sharice Davids

none

Though President Joe Biden signed a law requiring government entities to recognize same-sex marriages nationwide and the Supreme Court ruled that it’s unconstitutional to fire someone just for being LGBTQ+, Republicans in other states have pursued legislation to allow religious-based discrimination against LGBTQ+ people, including by medical providers. While the Biden administration has restored protections for trans and nonbinary students to access school facilities and sports teams matching their gender identities, Republican-led state legislatures and school boards have been trying to roll back these rights.

Polls have indicated that voters aren’t enthusiastic about a rematch between President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. Davids urges voters to not only consider the immediate issues facing their communities but also the long-term impacts of the policies we support, something her Native American identity as a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation has taught her to do.

“I ask questions about the long-term impacts — not for political purposes, but because it’s just kind of how I think about things,” she says. “We have responsibilities to our family, to our community, to our tribe; we have responsibilities to our country; and we have responsibilities to the people who come after us, but also to the people who came before us.”

Editor’s note: This article mentions suicide. If you need to talk to someone now, call the Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860. It’s staffed by trans people, for trans people. The Trevor Project provides a safe, judgement-free place to talk for LGBTQ youth at 866-488-7386 or text “start” to 678-678. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988.