Over 30 new LGBTQ education laws are in effect as students go back to school

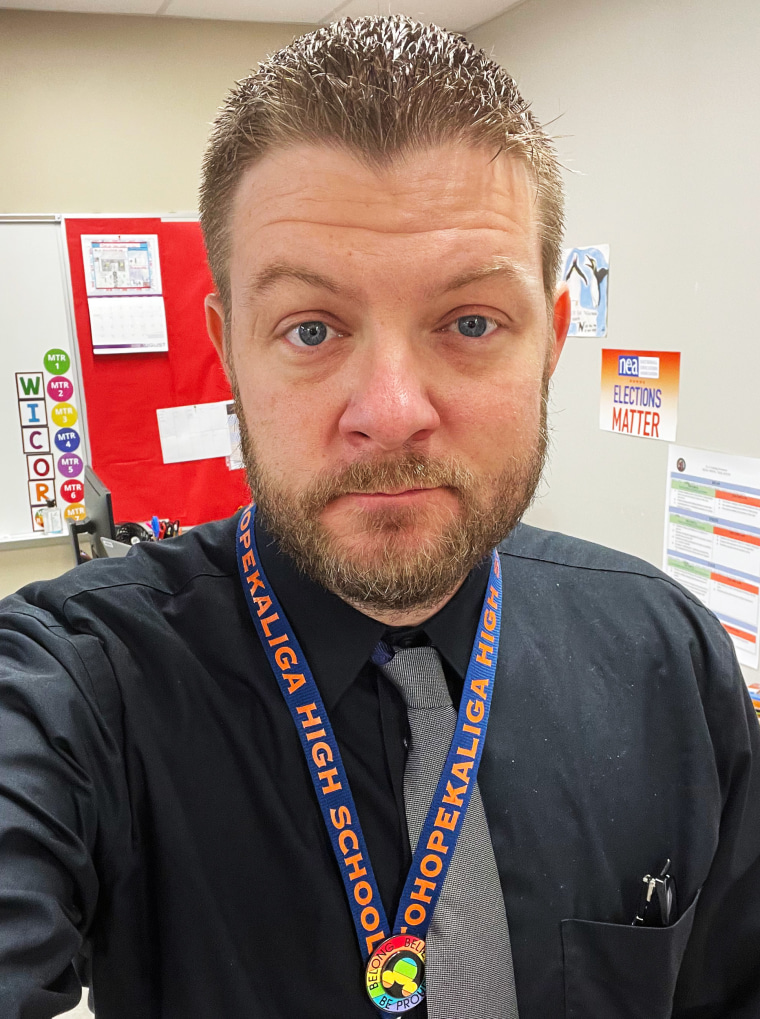

Brian Kerekes, a high school statistics teacher in Florida, said he froze like “a deer in headlights” when a student asked him a personal question at the beginning of the school year this month.

He said the student looked around the classroom, saw a small Pride flag, then asked, “Are you gay?”

Kerekes said that his identity is no secret and that he is one of a few out gay teachers in his school. But under a new state law that restricts the instruction of LGBTQ topics, he feared that his answer could somehow be illegal, he said.

“I said something to the effect of, ‘I don’t think I can tell you that,’” Kerekes said. “And she’s like, ‘Why not?’ And I said, ‘It’s kind of the state law now.’”

Kerekes said the exchange is just one example of the variety of difficult situations that he and his colleagues in Osceola County have had to navigate under Florida’s recently expanded Parental Rights in Education act, or what critics have dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” law.

Battles over what content is appropriate for children — in books, history classes, health classes and elsewhere — are dominating school board meetings and state legislatures across the country. In most of these debates, one side portrays LGBTQ-inclusive curricula and transgender-inclusive school policies as inappropriate or harmful for minors, with some conservative activists and elected officials going so far as to describe such content as “grooming,” resurfacing a decades-old moral panic about queer people.

Nowhere has that battle been more pronounced than in Florida, which made national headlines in the spring of 2022 when the state Legislature debated — and Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, ultimately signed — the so-called Don’t Say Gay bill. Initially, the measure prohibited “classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity” in kindergarten through third grade “or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” DeSantis signed an expanded version of the law in May that prohibits such instruction from prekindergarten through eighth grade and restricts health education in sixth through 12th grade.

Seventeen states enacted more than 30 new LGBTQ-related education laws in 2023, which will all be in effect for the 2023-24 school year unless they are blocked in court, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

In addition to Florida, five states — Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky and North Carolina — enacted restrictions this year on LGBTQ-related instruction in schools. Currently, 11 states have laws censoring discussions of LGBTQ people or issues in schools and several additional states have laws requiring parental notification of LGBTQ-inclusive curricula, according to the Movement Advancement Project, or MAP, an LGBTQ research think tank.

Iowa’s prohibition on the instruction of LGBTQ-related topics in kindergarten through sixth grade includes additional provisions that require school libraries to conduct regular reviews to ensure books don’t include sexually explicit material, allow parents to opt their children out of sex education and mandate school staff to immediately inform parents if they believe a child “has expressed a gender identity that is different” than the sex on the child’s birth certificate.

Ten states enacted new laws that bar transgender student athletes from playing on the school sports teams that align with their gender identities, bringing the total to 23 states, according to MAP, with the majority of these state measures applying to both K-12 schools and colleges.

Seven states have new laws that bar schools from requiring teachers (and, in some cases, other students) from using pronouns for students that don’t align with their sex assigned at birth. Florida’s expanded Parental Rights in Education act also bars transgender teachers from sharing their pronouns with students.

Five states have enacted laws so far this year that bar trans students and school staff from using school facilities that align with their gender identities, bringing the current total to nine states with such laws, according to MAP.

Florida also enacted a law that prohibits colleges and universities from spending state and federal funds on diversity, equity and inclusion programs. The law also restricts courses that could promote “social activism,” such as race and gender studies.

‘Educated, not indoctrinated’

Supporters of restrictions on LGBTQ-related content argue that it is inappropriate for children, and that parents should be allowed to determine their children’s access to such information.

“Parents deserve the first say on when and how certain social topics are introduced to their children,” Iowa state Rep. Skyler Wheeler, the Republican who sponsored the state’s parental rights law, said in March after the bill passed the state House, according to the Des Moines Register.

He added that “parents should be able to send their children to school and trust they are being educated, not indoctrinated,” nearly quoting language used by DeSantis when he signed the original version of Florida’s parental rights law.

DeSantis defended the expansion of the law after signing it in May, saying teachers and students would “never be forced to declare pronouns in school or be forced to use pronouns not based on biological sex.”

“We never did this through all of human history until like, what, two weeks ago?” DeSantis said of people using pronouns that are different from those associated with their assigned sex. “Now this is something, they’re having third graders declare pronouns. We’re not doing the pronoun Olympics in Florida. It’s not happening here.”

Students and educators ‘are under assault’

Becky Pringle, the president of the National Education Association, the largest labor union in the country, which represents public school teachers and staff, said the laws have created a culture of fear among educators nationwide.

“We are in a moment where our students are under assault, teachers and other educators are under assault, parents are under assault,” said Pringle, who taught middle school science for 31 years. “People are afraid. They’re afraid for their livelihood. They’re afraid for their lives.”

Pringle noted that the teacher shortage is “chronic and growing” across the country because teachers are dealing with unprecedented challenges, including the effects of the pandemic, burnout and low pay.

She pointed to a 2022 NEA survey that found 55% of its members said they were planning on leaving education sooner than they intended because of the pandemic, compared to 37% in 2021. On top of that, she said teachers have told her they feel like the public doesn’t respect their expertise, and the new laws are an example of that.

“That’s at the heart of what’s happening right now, where people who haven’t spent a day in our classrooms are telling us what to teach and how to teach and who to teach,” Pringle said. “We spend our lives trying to create those culturally responsive, inclusive, caring, joyful environments for kids, because we know that’s at the heart of them being able to learn every day.”

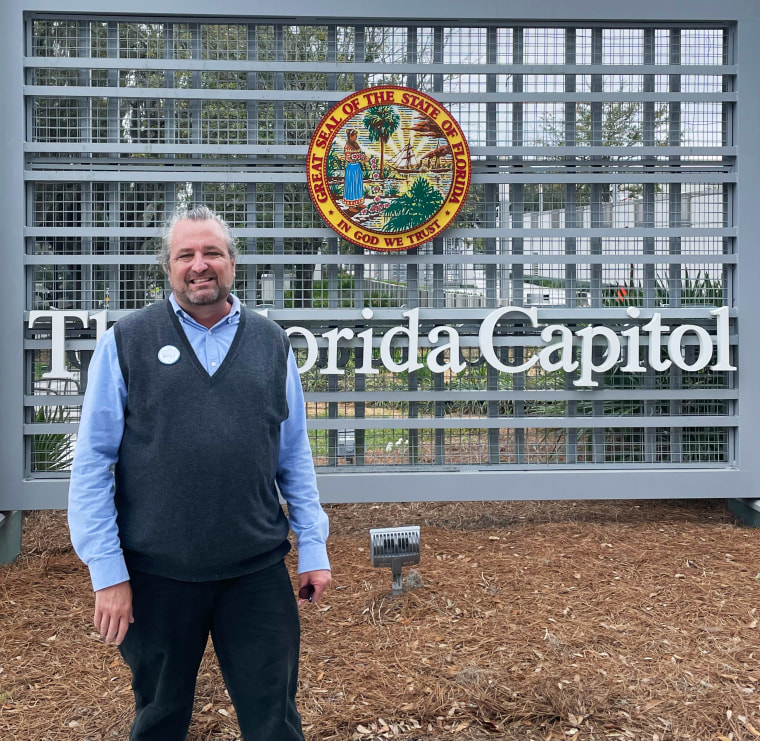

Michael Woods, a high school special education teacher in Palm Beach County, Florida, said he has encountered a number of difficult situations under the state’s new law. He has been advising a student for three years who uses a different name and pronouns than those assigned at birth. He said he’ll have to tell that student that he can no longer refer to them that way until they return a state-mandated form signed by their parents.

“We’re essentially telling kids, in my opinion, as a gay man, ‘You know what, go back in the closet,’” Woods said. “We’ve taken something as simple as a name that a student calls themselves and made it shameful.”

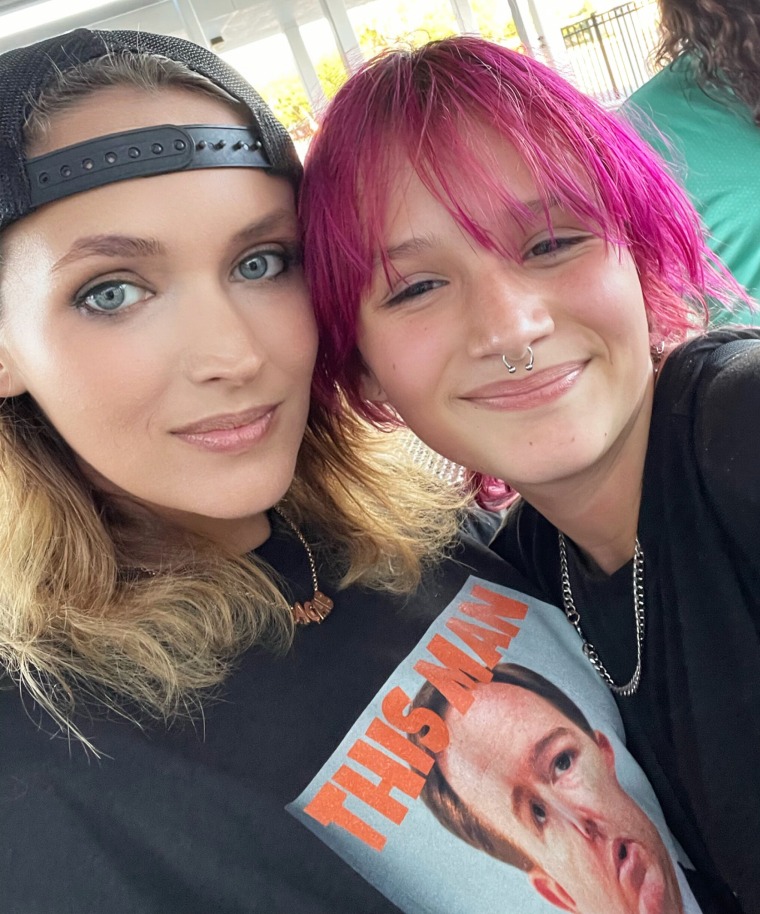

Lola, a 12-year-old seventh grader in Winter Haven, Florida, who uses gender-neutral pronouns, said the state’s new education-related laws have made kids in their school afraid to come out or talk about their identities publicly.

“A lot of students come out to me, because at school I’m openly queer and nonbinary,” Lola said.

They said students have also asked them questions about their family, because they have two moms, and in three cases, Lola said teachers told them they can’t discuss their family on school premises.

Lola’s discussion with their classmates would not break the law, which specifically mentions instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity from school staff. But Kerekes said teachers are avoiding LGBTQ subjects entirely out of fear that something they say or do could be interpreted as illegal or reported by a parent, who could sue the school district under the Parental Rights in Education act.

“I’m just talking about my parents,” Lola said. “Students shouldn’t be getting in trouble for talking about their life just because it’s different from the norm.”

Because of the part of Florida’s law that bars students from using bathrooms that don’t align with their assigned sex at birth, Lola said they have to walk to the nurse’s office, which is in a separate building, to use a unisex bathroom.

Lola said there are other trans kids at school who are too shy to ask to use a different bathroom, so they’ll avoid using the bathroom for the entire school day.

Advocates say legislation that removes LGBTQ-inclusive books and curricula or allows teachers to use the wrong pronouns for students harms their mental health, while supportive policies do the opposite.

Research released Thursday by The Trevor Project, an LGBTQ youth suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization, found that LGBTQ middle and high school students who had access to one of four school-related protective factors — gender-neutral bathrooms, LGBTQ-inclusive history lessons, a gender-sexuality alliance (GSA) club or teachers that respect their pronouns — had 26% lower odds of attempting suicide.

In Osceola County, Kerekes said he has inherited his school’s GSA club from a teacher who left last year. Some teachers in Florida, including Woods, have stopped hosting club meetings temporarily because they’re not sure how the new law affects them, but Kerekes said he will continue his school’s and hopes to have the first meeting this week.