Lesbian Visibility Week: 10 trailblazing queer women to celebrate

Over the centuries, lesbians and other queer women have pushed the world forward, often challenging norms and defying the expectations of their times. From 1700s England to the contemporary shores of New York’s Fire Island, these women forged new paths and made a space for others to do the same.

Some of those on this list lived at a time when there was no language for queer identity as in the present time, and often could not come out due to societal restrictions and concerns for their own safety. Like much of LGBTQ history, identifying who someone was requires squinting through the haze of the past and reading between the lines of diaries, historical records and second-hand accounts.

What is certain, though, is that queer women have always been around, even if their circumstances forced them to obscure their full selves.

Anne Lister (1791-1840)

Anne Lister, who has been described as “the first modern lesbian,” was born in northern England and lived during the height of the Industrial Revolution. Educated, wealthy and masculine in appearance, she had relationships with women beginning at an early age and by all accounts was unabashedly queer and self-assured, navigating her way around polite society while excelling as a businesswoman. Her womanizing reputation earned her the nickname “Gentleman Jack,” the latter part being a slur for lesbian at the time, but the name was reclaimed on Lister’s behalf, thanks to the BBC-HBO series “Gentleman Jack,” which ran from 2019 to 2022.

Though she did not use the word “lesbian” to describe herself, she wrote in her diary in 1821, “I love and only love the fairer sex and thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any love but theirs.” Lister married her neighbor and fellow landowner, Ann Walker, in 1834 at a church in York, England, an event considered to be the first recorded lesbian wedding in the history of Britain. Though it is unclear exactly what transpired at the church, experts are in agreement that the pair made vows to each other and exchanged rings. There was no legal recognition of the marriage at the time, but a commemorative plaque adorns the church and celebrates their union.

Dr. Margaret ‘Mom’ Chung (1889-1959)

Dr. Margaret Chung is best known as the first Chinese American woman to become a physician — and lesser known as a queer woman who attracted a clientele of lesbian couples and women seeking birth control.

Chung graduated from medical school in 1916 and was known to wear a dark suit and carry a parakeet around in a cage dangling from her wrist. During the 1930s and 1940s, she became known as “Mom Chung” for her support of U.S. troops, “adopting” hundreds of them, sending care packages and hosting soldiers for Sunday dinners at her home in San Francisco. Although Chung never came out, she did reportedly have intimate relationships with women, and rumors of her sexuality followed her throughout her life. A plaque hanging on Chicago’s Legacy Walk, which commemorates the contributions of LGBTQ people, celebrates her life.

Djuna Barnes (1892-1982)

Djuna Barnes was an avant-garde writer best known for her 1936 title “Nightwood,” one of the earliest lesbian novels to be published by an American writer. Barnes’ other well-known works include “Ladies Almanack,” published in 1928 and described as “a gentle satire of literary lesbians,” and the 1958 play “The Antiphon,” which The Paris Review described as a work that “concerns the war of wills within a family, primarily between a middle-aged woman and her mother.”

Barnes was a journalist before she was a novelist, poet and playwright. Her reporting stood out for being sensationalist and immersive, and she often tackled the political issues of her day. For an assignment published in New York World Magazine in 1914, Barnes submitted to being force-fed in prison, something that was being used on suffragists as they carried out hunger strikes.

Gluck (1895-1978)

An artist who defied the expectations of her day, Gluck was a British painter born Hannah Gluckstein in 1895. It is not clear how she would identify using the modern day’s vernacular, or if she would’ve considered herself a lesbian, but what is known is she had her short hair cut at a gentleman’s hairdresser, wore men’s suiting, kept a dagger hanging off her belt and was referred to as “Peter” among close friends, or as “Tim” by a female lover.

Gluck came from a wealthy family, and her privilege both insulated her and offered her the freedom to live a more open life. She had relationships with several women, including a playwright and society woman named Nesta Obermer. Gluck referred to Nesta as“my own darling wife,” and “my divine sweetheart, my love, my life.” She painted a portrait of them together, which later became the cover of “The Well of Loneliness,” a novel published by British author Radclyffe Hall in 1928 that is regarded as the first lesbian novel in the English language.

Gladys Bentley (1907-1960)

Gladys Bentley was a singer, piano player and entertainer who performed in the 1920s and 1930s, in the era that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Bentley was a powerful performer, and she was known for her top hat, tailored white tuxedos and risque lyrics. She did not conceal her sexuality but celebrated it, flirting with women in the crowd and incorporating a more masculine identity into her performances. She became one of the best-known Black entertainers of the time, and at the height of her fame she moved from Harlem to Park Avenue and had a team of servants. Bentley left New York in the late 1930s and performed throughout California, most notably Mona’s 440 Club, the first lesbian bar in San Francisco.

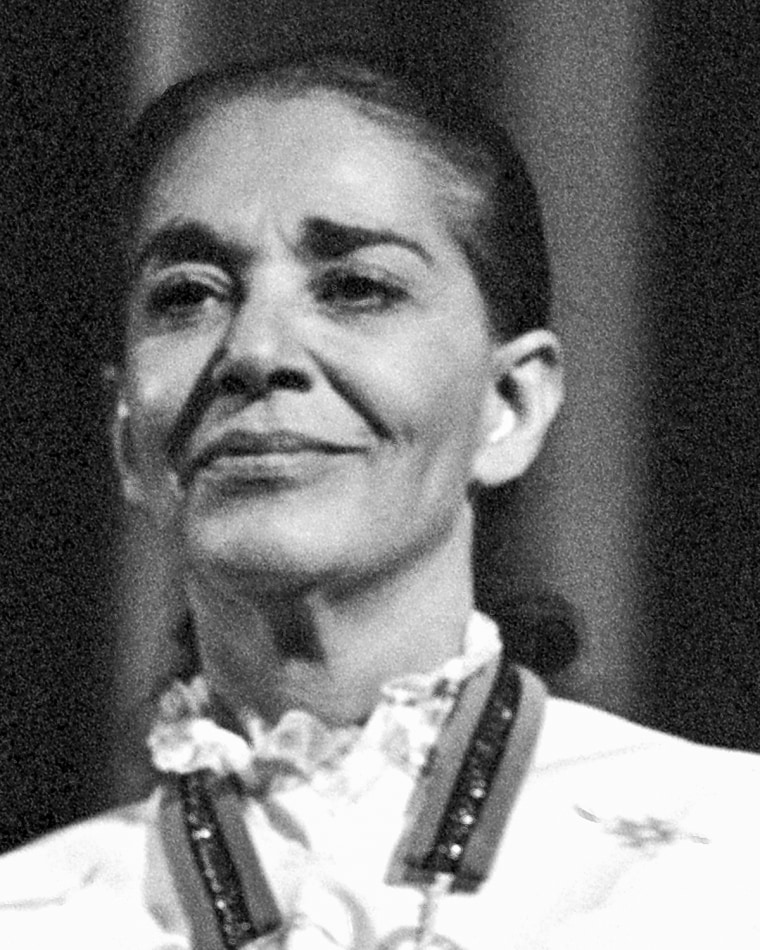

Chavela Vargas (1919-2012)

Born in Costa Rica in 1919, Chavela Vargas was 14 years old when she fled to Mexico with dreams of becoming a singer. She became one of Mexico’s best-known female singers, achieving dominance in the world of canción ranchera, a style that often includes broken hearts and unrequited love, mournful ballads traditionally told from a man’s perspective.

Recommended

U.S. NEWSKoko Da Doll, star in documentary about transgender sex workers, is killed in Atlanta

OUT HEALTH AND WELLNESSTennessee blocked $8 million for HIV, now ends up with $13 million, stunning advocates

Vargas rose to fame in the 1960s and 1970s, and had a reputation for being macho and drinking hard. While rumors long swirled about her being a lesbian, she didn’t come out until she was 81 years old, in an interview from the 1990s included in the 2017 film “Chavela.”

“When you’re true to yourself, you win in the end,” Vargas said.

Rosalie ‘Rose’ Bamberger (1921-1990)

In the 1950s, Rosalie “Rose” Bamberger had the idea to form a secret society for lesbians. The bars were constantly being raided, and Bamberger was looking to give women a space to meet one another that would be safe and private. She also wanted to dance without being arrested.

The first meeting was at Bamberger’s house in 1955, which she shared with her partner Rosemary Sliepen. The private club became The Daughters of Bilitis and morphed into the first lesbian rights group in the United States — and one that would eventually be surveilled by the CIA and the FBI. Though the club was Bamberger’s idea, she only lasted as a member for about six months, after a disagreement on the direction of the organization concerning her own safety as a working class woman of color.

Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965)

Lorraine Hansberry is best known for her 1959 play “A Raisin in the Sun,” about racial segregation in Chicago. It became the first play written by an African American woman to be produced on Broadway, and Hansberry, at 29 years old, became the first Black playwright and youngest American to win a New York Critics’ Circle Award. Activism was central to her life, and issues of racial equality, feminism and queer identity were all themes in her work.

She lived in New York’s Greenwich Village, which enabled her to have a more expansive life than was typically possible for women in the 1960s. Hansberry did not publicly come out during her lifetime, and most of what we know about her sexuality comes from her diary entries and other personal writings.

In a journal entry in 1962, she wrote, “The thing that makes you exceptional, if you are at all, is inevitably that which must also make you lonely.”

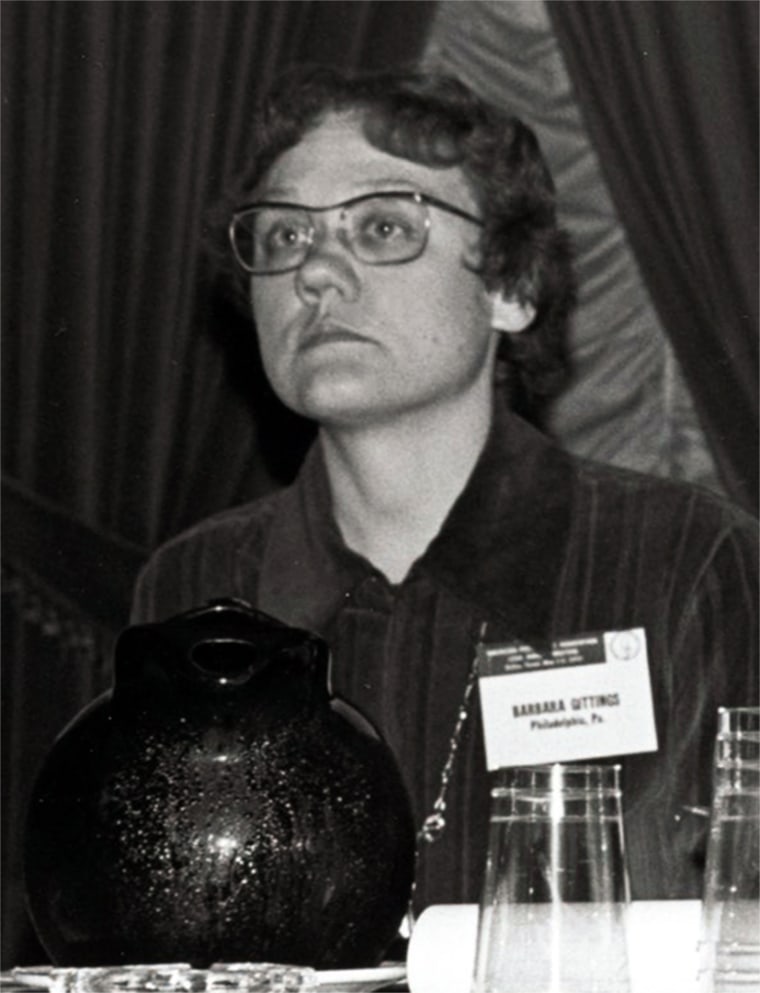

Barbara Gittings (1932-2007)

Barbara Gittings, often referred to as the “mother of the LGBTQ civil rights movement,” began her activism in the late 1950s — about a decade before the first brick was thrown during the 1969 Stonewall uprising.

She founded the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis and edited The Ladder, the first nationally distributed lesbian publication in America.

In the 1960s, she marched in picket lines at the White House, the State Department and Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Later, she was key in the 1973 decision by the American Psychiatric Association to end its classification of homosexuality as a mental illness. An advocate of education and books as a necessity for freedom and representation, she joined the gay caucus of the American Library Association in the 1970s. An LGBTQ library collection is named in her honor at the Independence Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Esther Newton (Born 1940)

Esther Newton is an anthropologist whose 1968 dissertation was titled “The Drag Queens: A Study in Urban Anthropology,” a work that foreshadowed her career as a trailblazer questioning and challenging societal expectations of gender, sexuality and anthropological methods. Newton’s dissertation became her first book, “Mother Camp: Female Impersonators in America,” which examined the world of drag bars in the Midwest in the 1960s. It was the first anthropological study of a queer community in the U.S., and that study would lead to a lifetime of work that provided a foundation for countless LGBTQ activists and scholars.