Queer people face discrimination in health care. Here are the people changing that.

When Constance Zhou got to college, they noticed that their queer friends were struggling with mental health. But they were also struggling to find providers well-versed in sexual and gender minorities or the complicated intersection of identities that often brought both discrimination and unique therapy needs.

At the same time, Zhou was working at a national suicide hotline, where many of the callers identified as LGBTQ+.

“I was getting people in Texas, in the Midwest, and in the South who really didn’t have access to resources,” Zhou said. “I began to appreciate how important it is to have access to mental health care and that it isn’t one size fits all.”

LGBTQ+ people face unique medical challenges related to sexuality and gender diversity. From experiencing higher rates of mental health stress and substance abuse to requiring gender-affirming care and treatment and prevention of HIV, needs stem from an array of factors related to how the healthcare industry and mainstream culture define identity. The criminalization of gender-affirming care in some states, as well as sports, bathroom, and book bans, contribute to the anguish faced by many in the queer community.

Medical understanding of the needs of queer people has come a long way since 1973 when activists successfully lobbied for the American Psychiatric Association to declassify homosexuality as a mental disorder. Indeed, advancements in health care have been hard fought by the community, often in the face of neglect and hostility by the medical establishment.

The federal government’s failure to respond to the HIV/AIDS crisis in the 1980s and ’90s further galvanized the queer community to take health care into its own hands. Gay Men’s Health Crisis (founded in 1982), the American Foundation for AIDS Research (1985), and ACT UP (1987) were among the early organizations to demand research, innovation, and medical access — efforts that drastically reduced HIV infections and eventually led to effective treatments and medications to prevent the spread of the virus.

That practice of forcing the medical establishment to address the health needs of the increasingly diverse community is underscored today by efforts to improve gender-affirming care for trans and non-binary people, a movement under attack with 11 states introducing bills to restrict gender-affirming health care access.

“There’s been an enormous amount of harm done to queer people in health care environments,” said David Baker-Hargrove, co-founder and former CEO of 26Health, an LGBTQ+ health care center in Orlando, Florida. “Sometimes, it’s out of willful discrimination, but it’s also from ignorance about how our needs differ and how to interact with and provide services to members of our community.”

Many such issues are systemic, as is the lack of culturally competent care to address the needs of LGBTQ+ people. Demographic differences among queer people also play a determining role in health risks and outcomes, reflecting entrenched social inequalities.

“There are disparities in our community — notably race, ethnicity, and class — that may not be sexuality specific and that drive unequal access to care and prevention services,” Gregg Gonsalves, an early member of ACT UP and today associate professor of epidemiology at Yale School of Public Health, told LGBTQ Nation.

Sexuality and gender identity are among the many considerations included in what the World Health Organization calls social determinants of health — non-medical factors, including economic means and access to education, that impact health risks and outcomes. Such factors account for up to 50 percent of variations in health outcomes in the U.S.

“Addressing social determinants of health is as important as medical interventions,” said Gonsalves, which means addressing factors like access to care is as necessary as developing effective treatment.

That’s where advocates like Zhou come in, with hopes of changing the system for the better. They are determined to help push for care that meets the community’s complex needs by working inside and outside the system for change.

“We’re survivors,” Baker-Hargrove said. “We know how to get along outside of existing systems, and it’s made us strong.”

LGBTQ Nation spoke to a range of queer people who were inspired by their personal experiences to become healthcare advocates and providers.

Constance Zhou co-founded the Weill Cornell Medicine Wellness Qlinic. José Romero advocates for people like themselves who are living with HIV to be part of the solution to ending the epidemic. Dr. Marci Bowers is a pioneering transgender surgeon whose personal experience transitioning informs both her push for innovation and sensitivity toward patients. And Anthony Sorensen was inspired by his own sobriety journey to found Transitional Recovery in Minnesota, which provides LGBTQ+ people in recovery with a supportive living environment.

Constance Zhou: creating new spaces for mental health

Growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina, Constance Zhou, 26, thought mental health was a storm that people weathered on their own.

That changed when Zhou got to college, where they grew comfortable identifying as queer and recognized that many queer people struggle with mental health and seek care, not only for anxiety or depression but for help developing a sense of self and to combat feelings of loneliness.

As a student, Zhou recognized the need for queer-affirming mental health care among their friends, as well as the LGBTQ+ people from around the country who called the suicide hotline where they worked. That led to Zhou’s decision to attend medical school to pursue psychiatry.

Zhou witnessed firsthand the disproportionate mental health stress that young queer people face and the need for more culturally sensitive and affirming providers to meet the demand.

“The issue became very personal to me, being part of the LGBTQ+ community,” Zhou told LGBTQ Nation. “I’m Asian American, queer, and trans. I also identify as nonbinary and use they/them pronouns. And within both the Asian American community and the LGBTQ+ community, there’s a lot of stigma surrounding mental health.”

Parental pressures to succeed in academics, pressure to live up to the “model minority” stereotype, and racial and cultural discrimination are some of the stressors cited in a University of Maryland School of Public Health study. Still, the stigma Zhou mentioned is often a deterrent to seeking help.

Motivated to improve the situation, Zhou decided to specialize in mental health at medical school but said that as a student, they “see that a lot of curricula in medical school really don’t focus on LGBTQ issues.”

Zhou, an M.D./Ph.D. candidate at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, co-founded with a classmate the Weill Cornell Medicine Wellness Qlinic, a student-run resource that provides mental health care to queer people while serving as a training ground for the next generation of practitioners.

“I see a lot of patients who are going through feelings and experiences that I have had before,” Zhou said. “Knowing that I can use my own background in understanding and helping them has been very rewarding.”

Co-founding the Wellness Qlinic within the first week of school was transformative. “I never really thought that the work that I did would be meaningful to my queer or trans identity,” Zhou said.

The Wellness Qlinic received immediate support from faculty and administration. “A lot of people went out of their way to make sure that we felt empowered to do what we needed to do,” Zhou said. The clinic, which opened in 2019 and has expanded to include 20 students on the board, functions as a resource for the patients it serves and those who run it.

“Part of the mission of the Wellness Qlinic is to provide free and culturally competent mental health care to queer and trans folks,” Zhou said.

Those services include patient evaluations, individual and group psychotherapy, and medication management. But the clinic also serves as an essential training ground for medical students, residents, and volunteers “to give them the skills they can use later on in their own practice.”

The Wellness Qlinic follows a pattern of similar organizations around the country offering mental health care specifically to queer people. Indeed, the number of clinics offering services specially tailored to LGBTQ+ people decreased by an average of 10 percent each year from 2014 to 2018. As of 2018, about one in five mental health clinics offer services specifically geared toward queer patients.

Nonprofit organizations like Queer LifeSpace, founded in 2011 to offer mental health services to people in the Bay Area regardless of ability to pay, have sprouted up to meet the need. Queer LifeSpace also offers a 12-month clinical training program to help foster the next generation of queer therapists. There are dozens of such clinics around the country. More are necessary to increase access to services for minority populations.

Educating providers is key to improving and expanding health care because, Baker-Hargrove noted, “most health care training programs, no matter the discipline, don’t have a lot of specific training geared towards LGBTQ+ competencies.”

Building community around HIV

José Romero has also experienced the power of community. As a public health advocate, Romero believes in building networks of mutual support in which people look out for one another. It’s a perspective rooted in personal history and informed by their experience living with HIV and pushing for greater accessibility and education around treatment and prevention.

“I’ve always been around people who have had to find ways to care for each other,” Romero, 30, said. Romero’s family emigrated from an impoverished part of Mexico to rural Washington State, where they worked as farm laborers. The nearest hospital to their small town was such a long drive that Romero’s mother nearly gave birth to them in the car. “I feel like I’ve been mobilizing for health care ever since,” Romero told LGBTQ Nation.

Romero’s first awareness he had been exposed to HIV was a phone call from a doctor.

“I had gone in feeling sick, and he asked me, ‘Do you have sex with men?’ When I said yes, he just immediately shut off to me,” recalled Romero, who identifies as non-binary. “He told me I had been diagnosed with HIV, and I should probably get a follow-up.” Romero made an appointment with another doctor, who was much more supportive.

Romero didn’t share their diagnosis for another five years when they started working as an organizer. “It’s taken other advocates and people who have lived experience supporting me to get to this point in my life where I’m using my diagnosis for good,” Romero said.

Today, they serve as director of community advocacy, research, and education at Pride Foundation, which gives scholarships to students and funds community organizations serving queer people throughout the Northwest. Pride Foundation was founded in 1985 out of a desire from people dying from HIV/AIDS to leave their money and legacies to benefit the community. Pride Foundation has distributed more than $74 million in grants to queer people and organizations advocating for equity and justice in the decades since.

Since the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the mid-1980s, annual infections in the United States have dropped by more than two-thirds, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. New HIV infections in the U.S. fell 8 percent from 2015 to 2019. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has set a goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030, and a number of city-based initiatives with similar aims are underway, including in former epicenters San Francisco and New York.

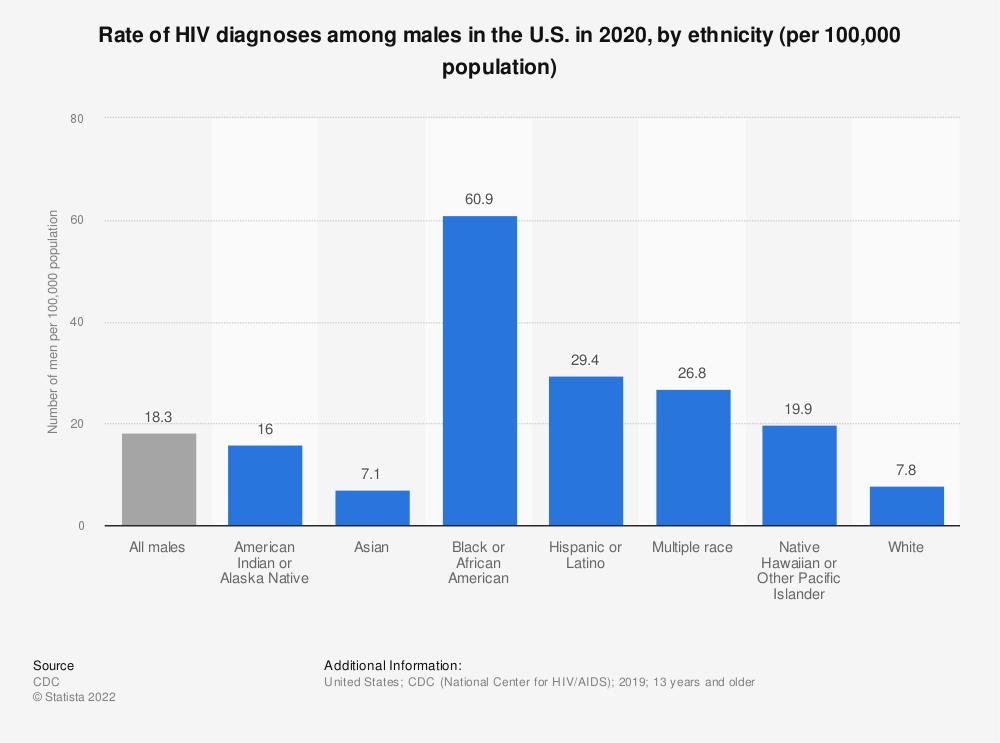

But men who have sex with men account for about 66 percent of new infections each year, despite being only 2 percent of the population, with Black and Latino MSM being affected disproportionately. Each group accounted for around a quarter of new HIV diagnoses among MSM in 2020.

Contributing factors to the high prevalence are intersectional and include racial discrimination, lack of access to resources, language barriers, and stigma. “It’s been really important for me to focus on this big issue by working in coalition and step-by-step,” Romero said. Since they grew up speaking Spanish, Romero recognized language as one of the biggest barriers to healthcare access. They have worked as a translator, interpreter, and advocate for hospitals to provide multilingual materials.

Though medical interventions for the treatment and prevention of HIV, such as antiretrovirals and PrEP, have extended lives and lowered infection rates, advocates are working to improve access for those who need it most, including racial minorities and trans people, who have been underserved by prevention efforts. “It wasn’t until recently that we’ve seen people who are not white or cisgender represented in media around HIV prevention and care,” Romero said.

The medications themselves aren’t enough, Romero said. “We need a social and cultural approach, and that means meaningful involvement of people living with HIV.”

Many factors put people at greater risk of negative health outcomes from HIV, including substance use, mental health, and access to stable housing. Social and political solutions that address these conditions are as important as medical innovations in the fight to end the epidemic.

“Structural interventions in the context of HIV prevention and care are going to need policy-level, community-wide solutions,” Gonsalves said. “This takes us back to the old days of LGBTQ+ advocacy — working to change the sort of environment in which we live to make it easier for us to keep ourselves healthy and safe.”

Half of all new HIV infections are located in the South, where Morris A. Singletary has been working as a peer educator to connect young men of color with care. Based in Atlanta, Singletary, 45, runs the HIV prevention and education initiative PoZitive2PoSitive, offering support and mentorship informed by his lived experience with HIV.

Singletary knows the stakes firsthand. He was near death when he received his HIV diagnosis in 2006, having not understood that he was at risk. And he struggled with the emotional fallout and with adhering to treatment for the next ten years. He also knows the shame, stigma, and lack of awareness that keep men from pursuing care.

“We have to be more intentional,” Singletary said. “We tell people to go to the doctor and get tested, but we don’t say what happens next. We need to show the cycle of care,” he added, including the patient’s role in communicating openly with providers who are trained to show support. Singletary noted that everyone involved in the healthcare process, from researchers and providers to peer educators like himself, has an integral role to play.

“Storytelling is an amazing tool,” Singletary said of the connections he’s forged through sharing his lived experience and encouraging others to seek HIV treatment and prevention.

Romero agrees that people living with HIV should be integral to the path forward, and encourages outreach organizations to hire them to reach others at risk or in need of care. “We need to invest in people to be the solution to the problems that we’re facing,” Romero said. “When we are provided with the resources and opportunity to help each other, we do.”

Dr. Marci Bowers: pioneering gender-affirming healthcare

Dr. Marci Bowers has devoted much of her history-making career as a surgeon treating transgender people, whose access to essential medical care has come under attack in recent years. Bowers, 64, has performed more than 2,000 vaginoplasties, or bottom surgeries, for trans women and is one of few surgical providers to have undergone the process herself.

“Everyone deserves access to gender-affirming care,” said Bowers, whose medical practice is based in Burlingame, California.

Growing up, Bowers knew she wasn’t comfortable with the gender identity she was assigned at birth, though it was a feeling she couldn’t describe. “I didn’t really have words for what it was to be trans,” Bowers said of the era when there were fewer role models and information. She wound up pursuing medicine, getting married, and having children, playing the role she felt was expected.

“I felt like I could displace my feminine feelings by being a woman’s health care provider,” Bowers said of her decision to become an OB-GYN. It was after Bowers transitioned, at age 37, that she considered pursuing a career in gender-affirmation surgery. “I was responding to an obvious need within the community for more providers,” Bowers said.

Insights gleaned by going through surgery herself have informed her sensitivity toward patients, “not just in the technical aspects of giving them what they want, but recognizing the struggle that they’d already been through being trans.”

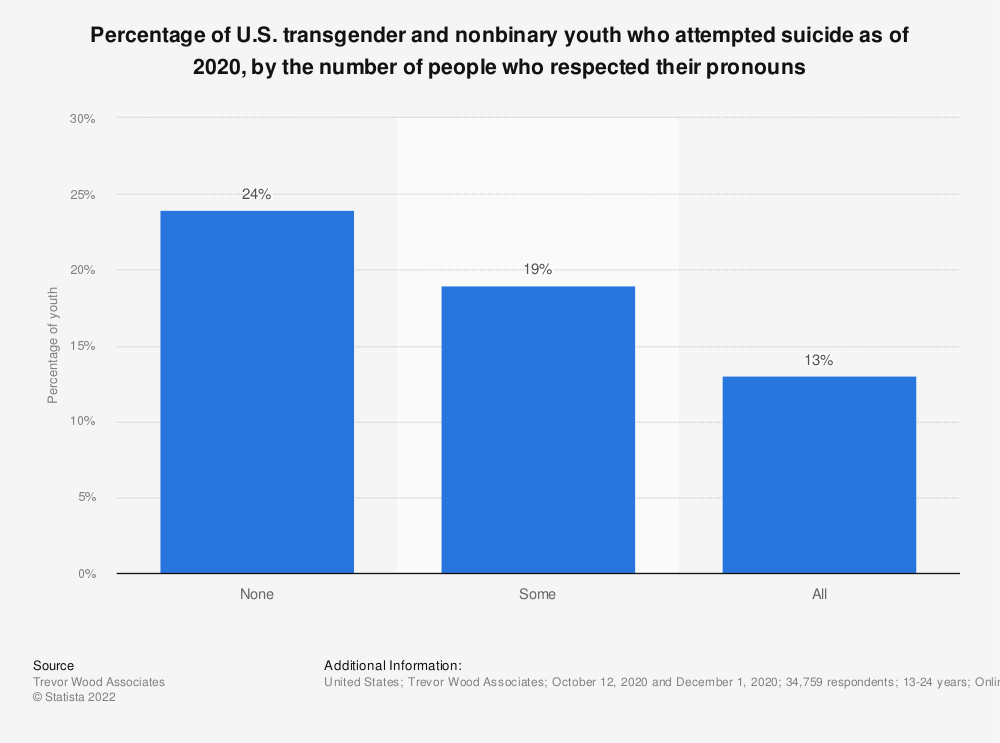

Trans people experience disproportionately high rates of anxiety and depression and are about six times as likely as the general population to be hospitalized for a suicide attempt. Recent studies have shown that gender-affirming care, including puberty blockers for trans adolescents, hormone therapy, and potential surgical interventions where necessary, significantly improve mental health and save lives. The latest guidelines from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health advised that hormone treatments can start from age 14.

“It’s an overwhelming, established fact that gender-affirming treatment is effective and greatly enhances psychosocial functioning and reduces suicidality,” Bowers said. “It’s about people improving their lives by assuming the identity that they feel most comfortable with.”

Even as the evidence of efficacy becomes ever more clear, gender-affirming care is being targeted across the country. As of March 2022, 15 states have restricted access to gender-affirming care or are considering laws that would do so. The consequences for people who need care are dire, cutting off access to treatment proven to improve well-being and reduce suicidality.

At the same time, the demand for gender-affirming care is growing, as is the corresponding need for more providers. “It’s growing because people are more comfortable being themselves,” said Bowers, who also helped establish the Transgender Surgical Fellowship Program at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City to help train more doctors to care for trans people. Under the Affordable Care Act, it’s illegal for insurance providers to deny medically necessary transition-related care, and Bowers also accepts Medicaid from her patients.

“People at every socioeconomic level should have access to this care; we’ve always felt strongly about that,” Bowers said. But even for patients who have coverage, there’s a need for more doctors to provide treatment. “We need more clinicians and mental health professionals to help with the care of this population,” she said.

“Gender identity is a very deeply held value,” Bowers said, an indelible one that requires affirmative care. “It weathers any storm.”

Providing homes for recovery

When Anthony Sorensen, 52, was growing up on Long Island, New York, his father — who struggled with alcoholism — would disappear for days at a time. When Sorensen was 16, his father left for good, and Sorensen blamed himself, thinking it was because he is gay. Sorensen had started drinking the year before, blacking out the first time he tried alcohol.

“I wanted to be the bad kid who got in trouble in order to feel cool and accepted by my peers,” Sorensen recalled. “But at the same time, to save myself from the humiliation of being called out as gay, I just wanted to disappear.

“The first time I drank, all those fears and inhibitions of being humiliated went away,” Sorensen said.

Feelings of alienation like those Sorensen described are among the reasons that LGBTQ+ people are more than twice as likely to abuse drugs and alcohol than the general population, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, a trend that’s been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. A variety of factors contribute to the increased likelihood, including concurrent mental health conditions like anxiety, depression, and suicidality, themselves often a result of marginalization, discrimination, and trauma.

Drugs and alcohol have also occupied a historically central role in how queer people relate to each other and form social bonds. “Our community was formed in bars,” Baker-Hargrove said. “It can be hard to think about a life within the community that’s not anchored to alcohol or partying.” That’s one reason substance abuse is sometimes normalized within the community, and it may be easier to overlook when someone is struggling.

Sorensen’s heavy drinking and drug use accelerated when he moved to New York City shortly after coming out at age 19. He was 23 when he attended his first Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, but it wasn’t until he discovered AA meetings that were mainly attended by queer people that he was able to work the program and stay sober for two years.

Sorensen’s first experience with Pride Institute, a treatment and recovery center especially focused on the needs of LGBTQ+ people, was in 1999, at a facility in Belle Mead, New Jersey, that has since closed. He stayed sober for 11 years before he began drinking again, when his career as a hairstylist took precedence over his recovery, Sorensen said.

Sorensen later completed two 30-day courses of inpatient treatment at Pride Institute’s main campus in Eden Prairie, Minnesota.

“Pride 100 percent saved my life,” Sorensen said. “Pride for me was the place where I knew I could authentically be myself without many of the fears that I had carried since I was a kid,” he recalled, noting that he was fortunate to have private insurance and a choice of where to seek treatment. Pride is in-network for most major insurers and works with uninsured patients on lending options to reduce financial barriers to care.

Pride Institute has pioneered a model of treatment specifically tailored to LGBTQ+ people. Since many patients like Sorensen can trace their struggles with addiction back to aspects of their queer identity, centering and affirming those aspects of their lives is essential to effective treatment. “If you can’t totally be yourself, you’re not going to move forward in your recovery,” Sorensen said.

Pride Institute’s affirming environment includes gender-neutral bathrooms and room assignments not based on gender identity assigned at birth, as well as peers and staff with lived experience who embrace and celebrate everyone for who they are. “The counselors are educated in LGBTQ+ issues and addiction and mental illness,” Sorensen said. “They made me sit with my feelings and work through them, rather than escape them” — a process Sorensen called life-changing.

Sorensen also credits the success of his recovery to transitional housing specifically designed for LGBTQ+ people, where those who have completed inpatient programs can live with others in a shared house and offer mutual support. “I saw the success that I had with transitional housing, and I want to be able to reach as many people as possible and give them that same opportunity,” said Sorensen, who ultimately decided to relocate to Minneapolis and dedicate himself to offering queer people in recovery a place to support each other.

A few years into his own recovery, in 2015, Sorensen founded Transitional Recovery in Minnesota (TRIM), which now runs two houses catering to queer people working through addiction. Sorensen works with local outpatient programs, including Pride Institute, which helps subsidize housing costs for patients so that 90 percent of TRIM’s residents have financial support to make the rent accessible.

“When someone comes into the house, they are 100 percent made to feel like they’re at home,” Sorensen said of TRIM, a model of affirmative support that Sorensen experienced at Pride Institute. “Whether a gay man or a transgender woman who walks through those doors, we all have a very unique set of experiences, but we go through similar things being a minority within our society.”

Though LGBTQ+ people face a variety of challenges based on other aspects of identity and social determinants of health, a sense of solidarity continues to be important in pushing for better health outcomes across the board. “We want everybody to survive, thrive, and prosper,” Gonsalves said, “and LGBTQ+ people need to think of activism as a component of fighting for their health and safety.”

Early activism during the AIDS epidemic continues to be the prime example. Gonsalves pointed to the recent Mpox outbreak and the queer community’s response as proof of how effective collective action continues to be, often in the face of a flawed institutional response.

“LGBTQ+ communities were essential over the past year in slowing down and putting the brakes on the epidemic,” Gonsalves said, noting the pressure placed on government leaders for accelerated vaccine access and the spontaneous reduction of sexual activity that slowed the spread. Unequal risk and access, based on factors like race and class, persisted, and policy-level change is necessary to protect the well-being of the queer community.

In the meantime, LGBTQ+ people continue to lead the charge, taking on disparities the community faces in the medical system and revolutionizing how we care for ourselves and each other.