More than 1,600 books banned during 2021-22 school year, report finds

More than 1,600 books were banned in over 5,000 schools during the last school year, with most of the bans targeting titles related to the LGBTQ community or race and racism, according to a new report.

PEN America, a nonprofit group that advocates for free expression in literature, released a report Monday, the start of Banned Books Week, that shows the sweeping scope of efforts to ban certain books during the 2021-22 school year.

It found that there were 2,532 instances of individual books’ being banned, which affected 1,648 titles — meaning the same titles were targeted multiple times in different districts and states.

Books were banned in 5,049 schools with a combined enrollment of nearly 4 million students in 32 states, the report found.

Because PEN America stuck to documented cases of bans, which included reports to the group from parents and school staff members and news reports about book bans, the report says its data most likely undercounts the true number of bans.

Suzanne Nossel, the CEO of PEN America, said the recent efforts to ban books are a new phenomenon that has been led primarily by a small number of conservative advocacy groups that believe parents don’t have enough control over what their children are learning.

“We all can agree that parents deserve to and are entitled to a say over their kids’ education,” Nossel said at a news conference PEN America hosted Monday. “That’s absolutely essential. But fundamentally, that is not what this is about when parents are mobilized in an orchestrated campaign to intimidate teachers and librarians to dictate that certain books be pulled off shelves even before they’ve been read or reviewed. That goes beyond the reasonable, legitimate entitlement of a parent to have a give-and-take with the school — things that are enshrined in parent-teacher conferences and PTAs.”

Preliminary data released Friday by the American Library Association, or ALA, found that the number of attempts to ban or restrict library resources in schools, universities and public libraries is on track to exceed the record counts of 2021.

From Jan. 1 to Aug. 31, the ALA documented 681 attempts to ban or restrict library resources, with 1,651 library titles being targeted, compared to 729 attempts for all of last year, with 1,597 books targeted.

The PEN America report said nearly all of the book bans — 96% — were enacted without schools or districts following the best practice guidelines for book challenges outlined by the ALA and the National Coalition Against Censorship.

Before the wave of book bans, parents would sometimes raise concerns to their children’s schools or teachers about books their children brought home, said Jonathan Friedman, PEN America’s director of free expression and education programs.

But now, conservative groups and parents are Googling to find books that have any LGBTQ content, and then a conservative group adds it to a list of inappropriate books, Friedman said.

“They complain about the books online, the books go on a list, the list takes on a sense of legitimacy, and then it being on the list leads a school district to react to that list and take it seriously,” Friedman said, adding that in nearly all of the cases, the cycle happens without respect for process or policy.

Friedman pointed to a case in Walton County, Florida, where a popular children’s book called “Everywhere Babies” landed on a banned books list last spring. A few of the illustrations include what could be interpreted as same-sex couples, but they are never identified as such in the text. The Florida Citizens Alliance, a conservative nonprofit group focused on education, included it in its 2021 “Porn in Schools Report.”

Of the 1,648 titles that were banned last year, the report found, 41% explicitly address LGBTQ themes or have protagonists or prominent secondary characters who are LGBTQ, and 40% include protagonists or secondary characters of color.

More than one-fifth (21%) directly address issues of race and racism, and 22% include sexual content of varying kinds, including novels with some level of description of sexual experiences of teenagers; stories about teen pregnancy, sexual assault and abortion; and informational books about puberty, sex or relationships.

Recommended

OUT POP CULTURESecurity appears to mistake drag queen for Lady Gaga at singer’s Miami concert

CULTURE MATTERSNew book spotlights experiences of gay sons of immigrants in Los Angeles

The report estimates that at least 40% of the bans listed on PEN America’s Index of School Book Bans are connected to proposed or enacted legislation or to political pressure from elected officials to restrict the teaching of certain concepts.

PEN America also found at least 50 groups involved in pushing for book bans, 73% of which have formed since last year. One of the largest is Moms for Liberty, a group advocating for parental rights, which lists more than 200 local chapters on its website.

Tiffany Justice, a co-founder of Moms for Liberty, said teachers should value parents’ input.

“I mean, there’s not two sides to this issue,” Justice said in an interview on “CBS Saturday Morning.” “There are moms who love their kids, who don’t want pornography in school, and then there are people who do want pornography in school. I think that the book issue has been used to try to marginalize and vilify parents. And the truth is there is no place for pornography in public schools.”

The 50 groups identified by the report have been involved in at least half of the book bans enacted last year, and at least 20% of the bans can be directly linked to the actions of the groups, the report found.

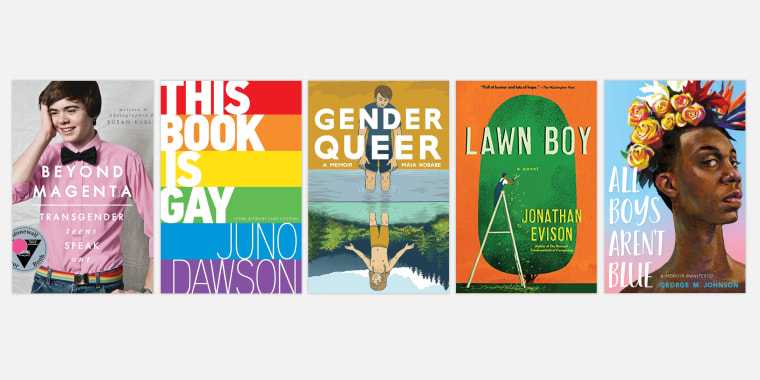

The most frequently banned books were “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” by Maia Kobabe, followed by “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” by George M. Johnson, and “Out of Darkness,” by Ashley Hope Pérez, the report found.

Pérez said what’s striking about her book’s being banned in 24 school districts is that it was published in 2015 and wasn’t challenged until last year. She said that some right-wing groups have used words like “pornographic,” “inappropriate,” “controversial” and “divisive” to describe the banned books and that the books they describe are most often by or about nonwhite people and other minorities.

“The books are a pretext. It is a proxy war on students who share the marginalized identities of the authors and characters in the books under attack,” she said at Monday’s news conference. “It is a political strategy. The goal is to stir up right-wing political engagement by drawing still brighter lines around targeted identities.”

She said banning books harms students in a few ways. When a student shares a gender or sexual identity with a character in a book and that book is banned, it “sends the message that stories about people like them are not fit for school.”

By giving into their demands, schools give conservative groups an unearned legitimacy, she said.

“When school leaders cave to these pressures, they elevate the questionable judgment of a handful of parents over the professional discretion and training of librarians and educators and, above all, above the needs of students,” she said.