From book bans to ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill, LGBTQ kids feel ‘erased’ in the classroom

Students have repeatedly vandalized Pride posters at Spencer Lyst’s high school in Williamson County, Tennessee. Teachers have skipped over LGBTQ issues in class textbooks. Trans kids in his state have been legally barred from competing on school sports teams that align with their gender identity. Parents have called on school officials to remove books about sexual orientation and gender identity from the county’s elementary curriculum. And while leading his school’s Pride club at a September homecoming parade, Lyst and other LGBTQ students were booed by a group of parents.

“I’m so used to it, but it shouldn’t be something I have to think about,” Lyst, 16, said of the near-constant feeling of being attacked at school because of his identity.

He even said it’s “difficult” to walk into the school bathroom for fear of what or who “might be in there.”

“Like, can I go to the bathroom or am I going to get hate for just existing?” he said.

Lyst’s school experience is a far cry from an isolated case.

Since the start of the school year, school officials in states across the country have banned books about gay and trans experiences, removed LGBTQ-affirming posters and flags and disbanded gay-straight alliance clubs. In school districts throughout the nation, students have attacked their queer classmates, while state lawmakers have filed hundreds of anti-LGBTQ bills with many seeking to redefine lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer students’ places in U.S. schools.

“There is no separating any of these things,” Mary Emily O’Hara, the rapid response manager at LGBTQ advocacy group GLAAD, said at a media briefing on Monday. “What we’re seeing here is anti-LGBTQ groups, on a national level, making schools the new battleground across the board, across various kinds of school policies and various forms of legislation. Schools are the target right now for the anti-LGBTQ movement.”

In the majority of cases, conservative school officials, lawmakers and parents say LGBTQ issues do not belong in school because they are “political” and “not age-appropriate” for students. Conversely, queer youth and their families, along with LGBTQ and ally teachers, say they feel they are being “erased” from the U.S. education system.

‘I’m not going back in the closet’

South Florida mom Jennifer Solomon, 50, has four children. Her eldest child, Nicolette, 28, is a lesbian who teaches fourth grade in Miami-Dade County. Her youngest, Cooper, 11, identifies as male, but Solomon said his “expression is female.” Cooper “never wanted to be a girl,” his mom explained, but he prefers to wear his school’s girls uniform and enjoys dressing up like a fairy-tale princess for fun.

“An easy way to describe it is that he’s the opposite of a tomboy,” she told NBC News.

Despite how hard she works to protect her children, Solomon — who leads her local chapter of PFLAG, an LGBTQ family advocacy group — said the slew of anti-LGBTQ school policies “keeps me up at night.”

On Monday, Solomon’s governor, Republican Ron DeSantis, signaledthat he would support a new piece of state legislation — titled the Parental Rights in Education bill, but dubbed the “Don’t Say Gay” bill — that would prohibit the discussion of sexuality and gender identity in schools.

Speaking at a news event in Miami, DeSantis said it is “entirely inappropriate” for teachers to be having conversations with students about gender identity, citing alleged instances of them telling children, “Don’t worry, don’t pick your gender yet,” and “hiding” classroom lessons from parents.

“Parental rights? Whose parental rights? Only parental rights if you’re raising a child according to DeSantis?” Solomon, who is a nurse manager at a health care company, said of DeSantis’ concerns. “DeSantis tries to paint this picture that every family is this 1950s mom and dad with two kids and a cat and dog. That is not what Florida looks like; that is not what the country looks like.”

“DeSantis has found a weak spot, and that weak spot is children,” she added, suggesting that DeSantis is supporting the measure for political gain.

Nicolette Solomon said she is already hesitant to mention her wife — and by default her sexuality — at school, but she said passage of the “Don’t Say Gay” bill would be “the straw that breaks the camel’s back” and vowed to quit if it becomes law.

“If I can’t be myself, seven hours a day, five days a week, then I’m going back in the closet, and I can’t do that. It’s not good for my own mental health,” she said. “And I don’t think I can bear to see the students struggle and want to ask me about these things and then have to deny them that knowledge. That’s not who I am as a teacher.”

In less than two months since the start of the year, conservative state lawmakers have filed more than 170 anti-LGBTQ bills — already surpassing last year’s 139 total — with at least 69 of them centered on school policies, according to Freedom for All Americans. The nonprofit group, which advocates for LGBTQ nondiscrimination protections nationwide, said in an email that it didn’t track LGBTQ school policy bills last year, as it was not as much of a “sweeping trend” as it is now.

Three states — including Lyst’s home state of Tennessee — passed bills last year that allow parents to opt students out of any lessons or coursework that mention sexual orientation or gender identity, according to GLSEN, an advocacy group that aims to end LGBTQ discrimination in education. In addition to the “Don’t Say Gay” bill advancing in Florida, there are 15 bills under consideration in eight states that would silence speech about LGBTQ identities in classrooms, according to free speech nonprofit organization PEN America.

But perhaps the biggest trend in state bills targeting LGBTQ youths are those focused on transgender students.

Last year, legislators in at least 30 states weighed legislation that would bar trans students from competing on school sports teams that align with their gender identity, according to LGBTQ advocacy group Human Rights Campaign. Nine of those states enacted the bills into law. So far this year, 27 states have proposed similar bills, with South Dakota enacting its version of the legislation into law this month.

While not school related, there has also been a slew of bills that seek to prevent transgender youths from accessing gender-affirming health care. At least 20 states have proposed such measures since early 2021, with two states — Arkansas and Tennessee — enacting these bills into law. However, a federal judge temporarily blocked the Arkansas law in July after the American Civil Liberties Union challenged it in court on behalf of trans youths and their families.

Cooper Solomon said he thinks lawmakers are pushing anti-LGBTQ legislation “because they were born in another time.”

“I guess back then, a long time ago, they didn’t accept this, and they thought it was really bad,” the fifth grader said. “I would just like them to know that it’s OK to be like this, and it’s not going to hurt anyone.”

Florida introduces bill banning schools from discussing sexual orientation

‘My community was under attack’

Legislation aside, the last straw for Jack Petocz, 17, was when his high school in Flagler County, Florida, removed a young adult memoir detailing the trials of being a Black queer boy: George M. Johnson’s “All Boys Aren’t Blue.”

In November, a school board member filed a criminal complaint against school officials for allowing copies of the book — which has been challenged in at least 19 states — to remain in two of the county’s high schools. The complaint was dismissed, but the superintendent decided to keep the book off of shelves until new policies are drafted to give parents more control over the library’s collection.

“I felt that my community was under attack, that they were trying to silence LGBTQ+ experiences and voices within our community,” Petocz, who is gay and led a student protest in response to the book’s removal, said. “We’re already a minority. Why are you trying to suppress this critical information within our libraries, you know? These books are critical to providing a sense of identity.”

Books about race, sexual orientation and gender identity have historically been challenged in schools, but over the last several months, school libraries have seen a surge of opposition.

In the fall, as book bans started to take off in counties across the country, national groups — including No Left Turn in Education and Moms for Liberty — began circulating lists of school library books that they said were “indoctrinating kids to a dangerous ideology” to rally support.

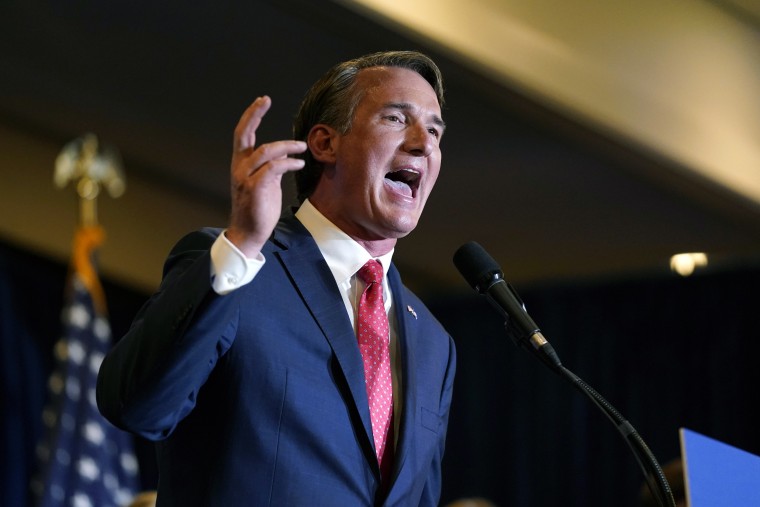

The bans then became a talking point in the contentious Virginia governor’s race, where the Republican candidate, former private equity executive and political newcomer Glenn Youngkin, made education a central issue of his campaign and swept to victory.

Youngkin’s victory prompted other politicians to jump onto the issue, with the governors of Texas and South Carolina urging state school officials in November to ban several books, deriding them as “pornography” and “obscene” content.

Recommended

OUT POLITICS AND POLICYTexas AG says transition care for minors is child abuse under state law

OUT NEWSTrans swimmer Lia Thomas wins 4 races at Ivy championships, heads to NCAA finals

School board members in Virginia’s Spotsylvania County made national headlines after calling for LGBTQ books with “sexually explicit” material to be incinerated.

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association Office for Intellectual Freedom, said in November that while challenges to books with LGBTQ- and race-related content have historically been “constant,” the association has recently seen a “chilling” uptick.

“I’ve worked at ALA for two decades now, and I’ve never seen this volume of challenges come in,” she said. “The impact will fall to those students who desperately want and need books that reflect their lives, that answer questions about their identity, about their experiences that they always desperately need and often feel that they can’t talk to adults about.”

To counter LGBTQ book bans — and school bans on race-related texts — a group of more than 600 writers, including bestselling children’s author Judy Blume; publishers; bookstore owners; and advocacy groups signed a joint statement in December condemning the trend, arguing it “threatens the education of America’s children.”

Setting a ‘different tone’

While state bills and book bans have garnered the most media attention, advocates say there are a host of other troubling trends adding to the distress that many queer students are feeling: removals of Pride flags and other LGBTQ-affirming symbols from classrooms, disbandments of gay-straight alliance clubs and resignations of teachers in protest of anti-LGBTQ policies.

In the fall, for example, rainbow stickers were ordered to be scraped off classroom doors at MacArthur High School near Dallas.

“While we appreciate the sentiment of reaching out to students who may not previously always had such support, we want to set a different tone this year,” an email from a school official addressed to school staff read. NBC News obtained the email from a MacArthur High School teacher.

The sticker removals prompted a protest from the student body, but the pushback did not successfully encourage school officials to change their stance on the policy.

School board members in Newberg, Oregon, made national headlines in the fall for taking similar actions. In September, the school board banned educators from displaying Pride and Black Lives Matter flags and other symbols it considered “political” in school.

“We don’t pay our teachers to push their political views on our students. That’s not their place,” the school board member who authored the policy, Brian Shannon, said at a recorded board meeting.

The policy prompted town protests that attracted some members of the Proud Boys, a far-right group that has endorsed violence, who counterprotested the efforts. An attempt to recall Shannon and another school board member over the flag removals failed last month.

Some teachers have resigned in school districts over similar measures, like a Missouri teacher who resigned in September after his district mandated that he take down his Pride flag and not discuss human sexuality or “sexual preference” at school. In December, parents accused teachers at a middle school in Tennessee of trying to “indoctrinate” kids into being gay after helping students start a gay-straight alliance club.

In addition to parents, school officials and lawmakers, classmates are among those targeting LGBTQ students, according to advocacy groups and local news reports.

A national survey of LGBTQ students published in 2020 by GLSEN found that 69 percent of respondents reported experiencing verbal harassment at school based on their sexual orientation, 57 percent based on their gender expression or outward appearance, and 54 percent based on their gender identity.

Last year, more than a dozen local news articles — from California to Florida — reported on trans students being harassed or attacked by other students, some of them in bathrooms. However, advocates say it is unclear whether the attacks have increased or whether local outlets are reporting them at greater rates.

Impact of affirmation

Advocates have long been warning educators about the mental health risks plaguing LGBTQ youths and how anti-LGBTQ policies can exacerbate them.

A survey last year by The Trevor Project, an LGBTQ youth suicide prevention and crisis intervention organization, found that 42 percent of the nearly 35,000 LGBTQ youths who were surveyed — and over half of trans and nonbinary youths — seriously considered suicide within the prior year. Separately, two-thirds of LGBTQ youths said debates about anti-trans legislation have impacted their mental health negatively, according to a small survey The Trevor Project conducted in the fall.

However, researchers at The Trevor Project have also found that LGBTQ youths who reported having at least one LGBTQ-affirming space — such as a school, home or workplace — were significantly less likely to attempt suicide.

With that in mind, Lizette Trujillo drives three hours a day back and forth to her 14-year-old transgender son’s school in Tucson, Arizona. From the time when he socially transitioned in 2015, Daniel’s school was open to the idea of letting him use the bathroom that corresponded with his gender identity — which Trujillo said was not a given in Arizona — and already had experience teaching trans youth.

Trujillo said while the commute “is not without its challenges,” sending Daniel to a school where he is “not ‘othered’” has made him happier.

“The biggest difference at my school is that I’m supported by all my teachers and the principal and staff; I have access to sports and the bathrooms,” Daniel said. “It makes learning easier.”

It also freed up space for his mother to focus on securing her son gender-affirming health care, filing for new identification documents and working through emotional hardships.

“What people don’t realize is that you’re not just worried about school when your child socially transitions,” Trujillo said. “As you start this gender journey, you start to hit walls, and you’re like, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize I needed that,’ or, ‘I didn’t realize that was going to be a problem. I didn’t realize we were going to lose family.’”

In response to the slew of challenges plaguing LGBTQ students and teachers, President Joe Biden has vowed to lend his support. Earlier this month, the White House issued a rebuke of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” bill, while connecting the legislation to the disputes happening nationally.

“Make no mistake — this is not an isolated action. Across the country, we’re seeing Republican leaders take actions to regulate what students can or cannot read, what they can or cannot learn, and most troubling, who they can or cannot be,” a White House spokesperson said in a statement to NBC News. “This is politics at its worse, cynically using our students as pawns in political warfare.”

Students ‘fighting for their basic rights’

There are a number of examples across the U.S. of students getting proactive and successfully turning around anti-LGBTQ policies.

Aaryan Rawal, 17, was one of more than 400 students in Fairfax County, Virginia, who successfully urged their school officials to reinstate two LGBTQ books in November. Rawal, who is gay, said he was relieved when school board members heeded students’ demands, but he lamented that the organizing efforts forced him to miss class and lose sleep.

“No student in any county in this country wants to go to school fighting for their basic rights,” Rawal said. “Instead of doing statistics homework or hanging out with friends, we were expected to go to school board meetings and lobby school board members for stuff that really shouldn’t be up for debate.”

Last month, a group of students in Palm Beach, Florida, met with their newly hired superintendent to describe their experience being LGBTQ in their county’s schools. They went around, one by one, and relayed stories of harassment and assault from students and bullying from teachers, according to two students who attended the meeting.

“Students have just gotten a collective consciousness that, ‘School sucks and because I’m LGBT this is to be expected,’ and that’s not normal,” Marcel Whyne, a nonbinary high school student who attended the meeting, said. “That shouldn’t be the level of standard that we have for LGBT kids. You’re entitled to be treated like your peers and go to school and, you know, just be bored at school like a normal student, not terrified that you’re going to be harassed and have photos taken of you and be embarrassed and assaulted just because you’re trying to be who you are.”

As for Spencer Lyst, in Tennessee, he set out to start his high school’s Pride club, Indy Pride, last fall with the goal of spreading awareness about the school’s LGBTQ community and providing “a place for people who may feel like they don’t have one.” While being booed by adults at his school’s homecoming was a “difficult” experience, he said he remains undeterred.

“People should know that no matter what bill they try to pass or book they try to ban or thing they try to ban teachers or students from talking about in schools, it doesn’t change who people are, and it doesn’t change who we’re going to continue to be,” Lyst said. “So trying to take a legal route to ‘protect your kids’ doesn’t work. They are who they are, and if you can’t accept that, maybe it’s you who has some work to do.”