Transgender people in ‘survival mode’ as violence rises, anti-trans bills become law

Last Saturday, Que Bell led a vigil for Transgender Day of Remembrance, an annual observance to honor the memory of transgender homicide victims that began in 1999.

Bell has led these vigils before. He is the executive director of the Knights and Orchids Society, a nonprofit group based in Selma, Alabama, that supports Black transgender, queer and gender-nonconforming people, and he has been an advocate for more than a decade. But this year will be different.

“This is literally the first time that I’ll have to write down my best friend’s name for a TDOR celebration,” Bell said, using the initialism for Transgender Day of Remembrance. “It’s really going to hit differently.”

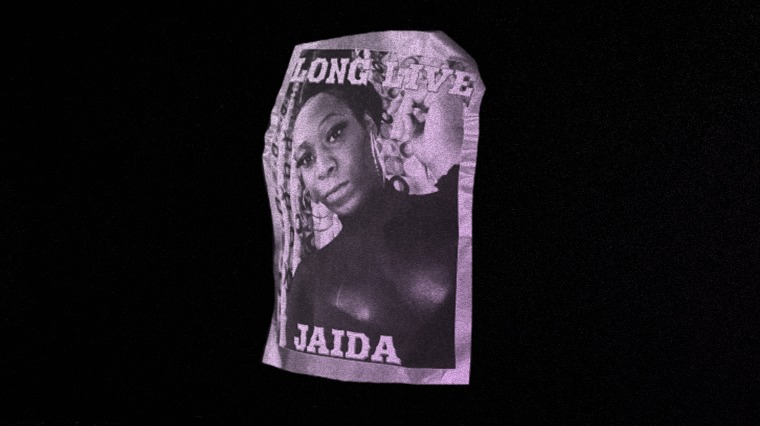

Bell’s best friend, Mel Groves, died Oct. 11 after having been shot multiple times. Groves, 25, a Black transgender man, was studying plant and soil science at Alcorn State University in Lorman, Mississippi. Just before he died, he was about to become the full-time community garden manager for the Knights and Orchids Society.

But on Saturday, Bell will light a candle in Groves’ memory.

Groves is one of at least 47 transgender or gender-nonconforming people — and one of 28 Black trans people — to have died by violence in 2021, which has surpassed 2020 to become the deadliest year on record for trans people, according to the Human Rights Campaign, which has been tracking fatal anti-trans violence since 2013. A disproportionate number of the deaths have been in the Southeast.

State legislatures across the country this year have also considered a record number of anti-transgender bills — more than 100 — many of which target trans youths, specifically trans girls. Advocates say the rhetoric coming out of legislatures is connected to the violence, because it describes transgender girls as boys and vice versa and, in many cases, characterizes trans people as “predators”on sports teams or in bathrooms.

Transgender Day of Remembrance is also known as Transgender Day of Remembrance and Resilience — the latter part an effort to remind people that while trans people face disproportionate discrimination and violence, they are also leading grassroots efforts to make things better for their communities.

Deadnaming, misgendering and clearance rates

Bell said that he and Groves’ friends and family ultimately want the person who killed Groves brought to justice but that he doesn’t have confidence in the police investigation.

When the Jackson Police Department first reported on Groves’ death, it used his legal name and misgendered him, causing local news outlets to repeat the mistakes. Groves’ loved ones had to reach out while grieving his loss to ask news outlets to update their stories to reflect who Groves actually was. Some updated their stories; others said they couldn’t change them without confirmation from law enforcement authorities or Groves’ immediate family. https://iframe.nbcnews.com/nt4ufYW?_showcaption=true&app=1

A week after Groves died, Jackson police provided the same statement to NBC News that they first issued, which used his birth name (also known as deadnaming) and misgendered him. The police department hasn’t responded to a request for comment about whether it plans to update the statement.

Bell said police officials need to be more educated about what the trans community faces; otherwise, he said, they will be unable to solve the case. He recalled one officer’s public statement that he would investigate Groves’ death just like any other.

“That is totally avoiding the issue,” Bell said. “I want you to be knowledgeable enough to know that, when something happens to trans people, how your department should be reacting to it and how you can help, versus being so defensive about acknowledging that this happened because it was a trans issue.”

Bell said police need to understand that anti-trans violence is connected to discrimination and higher rates of homelessness, among other issues that trans people face, or “we’re never going to be able to solve the problem.”

Anti-trans fatal violence cases nationwide appear to have a lower average clearance rate — the percentage of cases in which someone has been arrested, charged and turned over to a court for prosecution — than fatal violence cases in general, said Brendan Lantz, an assistant professor of criminology and criminal justice at Florida State University.

Lantz and his research team at the university’s Hate Crime Research and Policy Institute are creating the first database to track fatal violence against the transgender community. Although the Human Rights Campaign and other nonprofit groups track such deaths, the database Lantz’s team is creating, which will date to 2012, also tracks characteristics of the offenses, victims’ background information, perpetrators’ information, handling by police departments (including whether victims were misgendered or deadnamed) and whether cases have been solved, among other information.

TransAmerica

Preliminary data, which Lantz said are subject to change, show that the nationwide clearance rate for fatal anti-trans violence is about 44 percent, which is well below the national average of 60 percent to 70 percent.

Recommended

OUT NEWSFormula One racing star wears LGBTQ Pride helmet at Qatar Grand Prix

OUT NEWSThese 8 U.S. cities failed an LGBTQ equality evaluation

Early patterns also show that there’s “very likely a correlation between the prevalence” of deadnaming or misgendering by police and the likelihood of clearing a case, he said.

Evidence is important when police are trying to solve a homicide, he said, “and if we’re not even using the correct name, obtaining that evidence isn’t particularly easy to do, right?”

“Witnesses are less likely to come forward, and a lot of issues enter the equation,” he said.

Transgender rights groups say anti-trans sentiment, reflected in bills considered in dozens of states, affects how trans people are treated, including by police. Police initially misgendered victims and used their birth names in reporting on 30 of the 46 known deaths, an NBC News analysis found.

Since 2013, about 80 percent of trans people in deaths involving trans people with available data were initially misgendered by the media or law enforcement, according to a report released Wednesday by the Human Rights Campaign. An NBC News analysis of this year’s cases found that victims in 73 percent of investigations were misgendered or deadnamed by police, compared to 59 percent of cases in which someone was arrested and charged.

‘A sense of survival mode’

Trans advocates say some policymakers and national advocacy organizations are quick to suggest police reform as a solution.

But while many of them agree that improving police competence and investigations is important, they say the strategy addresses the issue only after the fact — when people have already died.

That leaves many in the transgender community feeling unsafe, which has led some of them to take their safety and well-being into their own hands.

“When you get tired of depending on a system to protect you that you know was not designed to protect you or to support you, you realize that you’re literally wasting time and resources putting money into a system that is not going to change,” Bell said. “So instead … we decided to start investing in the things that we could tangibly change.”

Advocates like Bell say community organizations should be given more resources and support, because they know how to best keep their people safe and help them thrive — by providing them with gender-affirming health care, as the Knights and Orchids Society does, or housing, as a number of trans-led groups across the country do.

Mariah Moore, a national trans rights activist and a co-director of the House of Tulip, a nonprofit collective creating housing solutions for trans people in Louisiana, said: “It’s so important that we support community-led initiatives, because those folks leading those initiatives are actually folks who have that lived experience and are able to speak to the needs and actually distribute those resources directly to impacted community members.”

Bell echoed that sentiment with respect to funding for nonprofit groups. He said that many people support and know of national advocacy organizations but that the groups aren’t providing emergency housing or money for trans people.

“I’m committed to this work to always keep trans folks safe,” he said, adding that he has been evicted twice in the past because he has provided a place for people experiencing homelessness to stay, some of them as young as 13.

“That comes out of a sense of survival mode,” he said. “I don’t have a lot, but what I do have I want to share with the folks who are like me who also don’t have.”

In neighboring Georgia, Toni-Michelle Williams, the executive director of the Atlanta-based Solutions Not Punishment Collaborative, a Black trans- and queer-led organization that builds community safety through organizing and leadership training, said the group has supported more than 160 people through its Taking Care of Our Own Fund, which provides funding for emergency bail, housing, health care and other needs.

The group provided the support with less than 3 percent of $15 million, Williams said, which represents this year’s budget increasefor the Atlanta Police Department.

“Just imagine what we could do for our communities — Black trans and queer folks, sex workers, formerly incarcerated people — with at least 3 percent of that funding,” she said. “I definitely just want to encourage people to continue to push and to join our side around what it means to reallocate funding from these large institutions that have so many resources. Our communities are in need of them.”

Looking ahead, Bell said he’s determined “not to lose another Mel.”

“I want to do everything I can to make sure that we don’t have any more Mel Groves — that we don’t have another person who slips through the cracks, that for whatever reason we have the resources to make sure that folks have a fighting chance,” he said.

He added that he feels as though he has done a disservice to trans people who have been killed in the past. “Because what I don’t want people to remember about Mel is that he was the 39th person murdered,” Bell said. “And that’s often what happens when we lose somebody, is that the tragedy of their death is highlighted over their legacy, their purpose and all the good things that they have contributed to the world during their time.”

He wants people to remember that Groves was a promising scientist and that his professors bragged about him and his research after his death. He loved Nat King Cole, he had a smile that made people want to talk to him, and he always offered to share food with his friends.