Intersex people have been challenging ‘gender-normalizing surgery.’ Doctors are starting to listen.

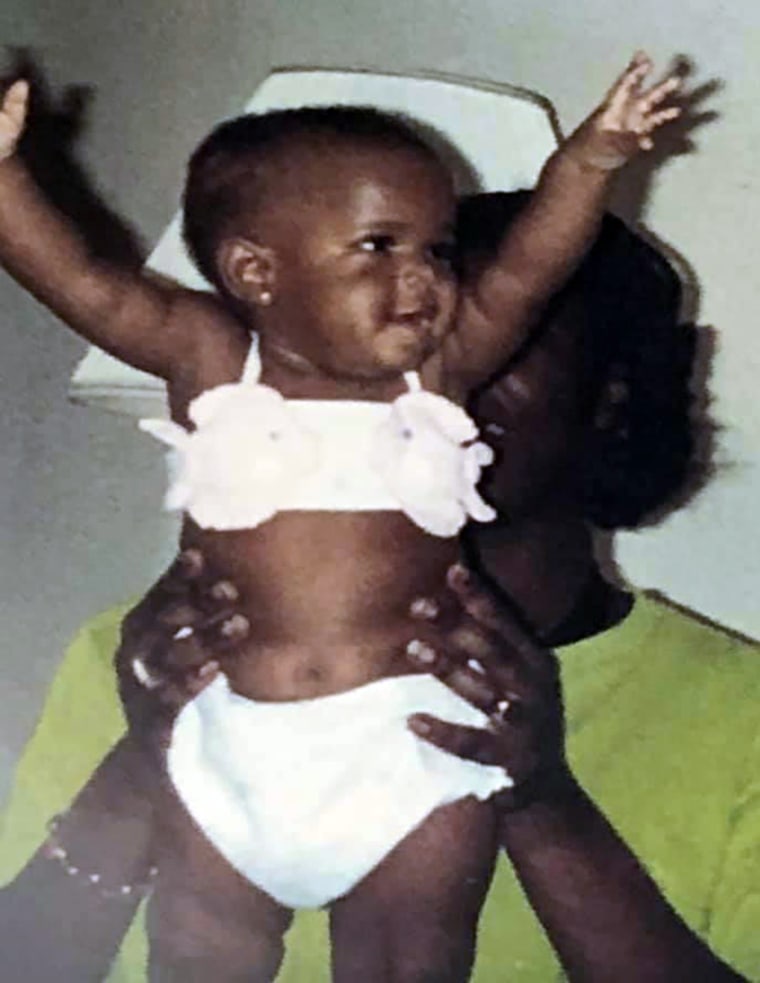

Bria Brown-King, 29, a Pennsylvania native, was raised as a girl. As Brown-King got older, however, they realized they were developing differently.

“I didn’t have the feminizing puberty that the other girls in my class had,” said Brown-King, who was born with an enlarged clitoris and started to develop masculine traits during puberty, including facial hair and larger muscles.

Brown-King, who has since come out as nonbinary and uses gender-neutral pronouns, was born with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, or CAH, a rare condition in which the body produces high levels of androgens — hormones that influence masculine characteristics. Those with CAH are considered intersex, an umbrella term used to describe individuals whose sex characteristics do not match strictly binary definitions of male or female. While rare, at least 1 in 2,000people are born with a genital difference caused by an intersex trait, according to Human Rights Watch, an international research and advocacy group.

Though many children with CAH undergo “gender-normalizing surgery” to make the genitals look more typically female in infancy, Brown-King’s parents decided to wait until Brown-King was old enough to choose. But Brown-King said severe bullying over their appearance drove them to get the surgery at 13. Looking back, Brown-King, who now works for InterAct, an intersex advocacy group, said they would have made a different choice “had I known that it was OK to have the body that I had.”

These so-called gender-normalizing surgeries have been performed on intersex babies and toddlers since at least the 1950s — usually in secrecy, without ever telling the children when they get older. Until recently, doctors saw a genital difference as a “psychosocial emergency” and rushed to assign a gender and perform surgery, believing children would be psychologically harmed otherwise, according to Dr. Sue Stred, a retired pediatric endocrinologist who has worked with intersex youth for nearly three decades. Emergency surgery, however, is only necessary in rare cases — if a child can’t urinate properly, for example, according to medical experts who work with these children.

The exact number of hospitals that currently perform these surgeries is unknown, and only a handful specialize in such procedures. Adults who underwent these surgeries as children report mixed feelings, with many saying they have had no problems, while others say they are “just wrought with devastation” over complications, according to Kyle Knight, a senior researcher who interviewed dozens of intersex people for Human Rights Watch. Complications can include sexual dysfunction, loss of sensation, infertility and gender dysphoria, according to the report.

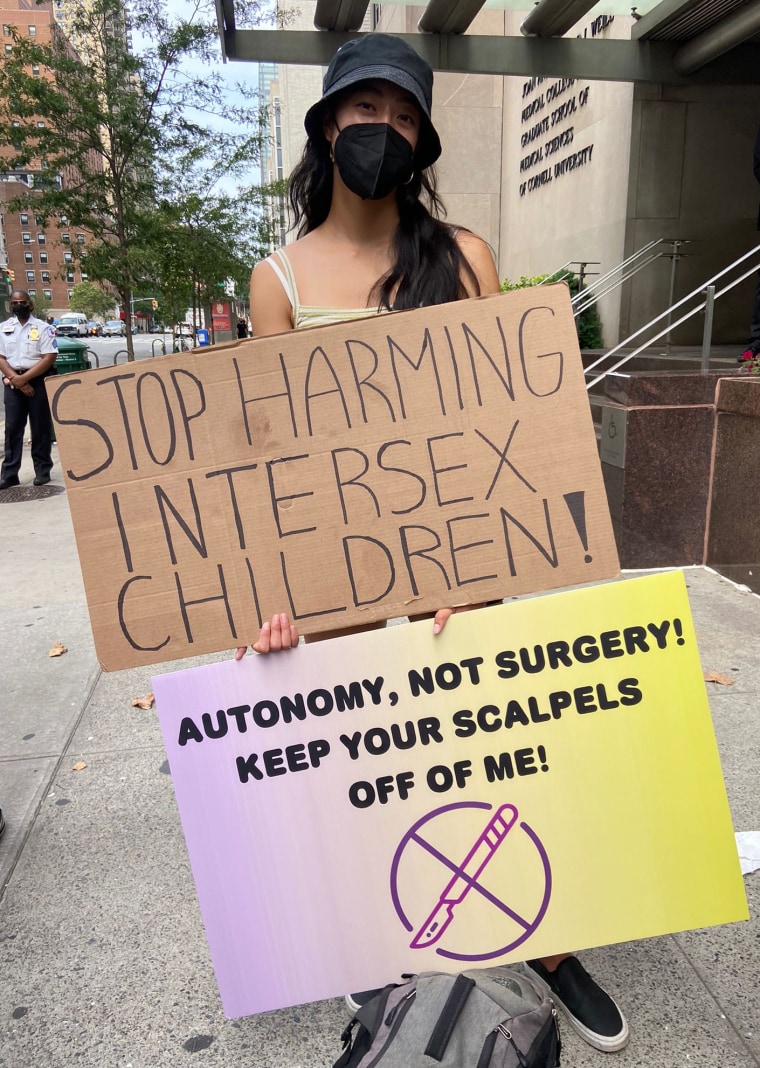

As more people tell their stories, an increasing number of organizations have condemned medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex youth, including the United Nations, the World Health Organization, Physicians for Human Rights, the American Academy of Family Physicians, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Under mounting pressure, several hospitals have recently announced they would defer certain medically unnecessary genital surgeries until children are old enough to participate in the decision, including Lurie’s Children Hospital in Chicago, Boston Children’s Hospital and New York City Health & Hospitals, the largest public health care system in the United States.

“We empathize with intersex individuals who were harmed by the treatment that they received according to the historic standard of care and we apologize and are truly sorry,” Lurie Children’s Hospital announced in a statement last year. It was the first time a hospital had ever made such an apology.

‘The right answer right now isn’t clear’

There is fierce disagreement among doctors and advocates over whether surgical delays should extend to those with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Unlike many other intersex youths whose genetics and reproductive organs make it difficult to assign a sex, those with CAH have distinctly male or female chromosomes and sex organs — and only those assigned female at birth undergo surgery because of genital and hormonal differences.

As such, some people who work with these children wonder if delaying surgery would do more harm than good. Even adults with CAH are divided over this. A recent study from Europe, which surveyed 459 intersex adults who underwent genital surgery as children, found that 66 percent of those with CAH thought infancy or childhood was an appropriate age for this surgery, while 12 percent thought they would have been better off without it.

Given these complexities, doctors and advocates have argued over whether children with CAH should be exempt from potential laws and policies that protect them from early cosmetic surgery. This was the case last year in California, when lawmakers, advocates and physician groups sparred over whether a bill, which would ban unnecessary surgeries on children with genital differences before age 6, was too broad. The bill, which was strongly opposed by the California Medical Association and Societies for Pediatric Urology, a group that represents the doctors who treat these patients, did not pass.

“The right answer right now isn’t clear,” Dr. Beth Drzewiecki, chief of pediatric urology at Tufts Children’s Hospital in Boston, said. “However, a blanket ban on surgery will not accurately support the views and voices of all of those that have variations in sex development.”

While Lurie Children’s Hospital has ended early medically unnecessary surgeries, it is considering an exemption for children with CAH, who experts say make up a majority of those who undergo feminizing surgeries. In an email, a spokeswoman for the hospital said the surgeries “will not be performed on CAH patients until we have evaluated the best practices and ethics and have released a white paper or report on the topic.”

The risks of ‘gender-normalizing surgeries’

There are no laws in the U.S. that regulate medically unnecessary gential surgeries for intersex children, Meanwhile, the current standard of care “remains an interdisciplinary team approach informed by parents’ wishes,” according to the AMA Journal of Ethics.

Taking this approach, more hospitals are hiring teams of surgeons, psychologists, social workers and genetic experts who work together to better understand a baby’s unique specific intersex trait, a process that can take weeks or even months, according to experts who work with these children. And doctors today are less likely to rush to assign a gender, though this may not always be the case.

“We still make recommendations for what gender we think the child is best going to feel, and we work that way,” Stred said. In cases where it is difficult to assign a sex, she said some doctors may recommend giving the child a gender-neutral name in case the child later disagrees with what sex they have been assigned.

Surgical techniques have improved greatly since the 1950s, with a better understanding of how to preserve sensitive nerves and tissue, according to Drzewiecki. She also said more surgeons today are giving parents options, rather than recommending surgery as a default solution.

“It’s really, I think, important to affirm to the families that their child is going to be OK with or without surgery,” she said, adding that “the most important thing is having transparency about what the risks are, and what the long-term risk over time will be, as well.”

One risk for those with CAH is stenosis, a condition in which surgically altered vaginal openings — performed in order to separate the urethra from the vaginal canal, which are typically fused in these children — can narrow over time, according to doctors. While the procedure is done to create a more typical vagina, doctors say it may be medically necessary to prevent urinary tract infections in some children, though the need for this is debated. A contentious way to prevent stenosis has been for parents or doctors to periodically insert a dilator in the opening to maintain it, though experts say this is usually traumatizing for children and, as such, is rarely done anymore.

Stenosis can lead to issues with menstruation and sex later in life, and may require additional surgery to fix, according to Dr. Frances Grimstad, a pediatric and adolescent gynecologist at Boston Children’s Hospital, who has training in these surgical repairs. And in general, she said, any early surgery performed on a child’s genitals is “playing a guessing game” as to what they will need or want in the future. Overall success rates of early surgeries are hard to pinpoint, she added, since health and insurance databases don’t accurately track them, and medical research tends to focus only on early outcomes.

Recommended

OPINIONHow Kyrsten Sinema became the worst kind of bisexual stereotype

OUT NEWS‘Worst List’ names 180 colleges that are ‘unsafe’ for LGBTQ students

“Surgeons who are doing these surgeries typically don’t follow their patients into their early 20s,” she said.

Brown-King said they developed urinary tract infections both before and after surgery and had to get additional surgery at age 19 to fix scar tissue.

“Surgery doesn’t fix everything,” they said. “I think that that’s kind of a narrative that sometimes doctors like to paint, that once you have surgery, things will be great. But that’s not necessarily the case.”

Surgery can also lead to mental health problems later in life, especially for those whose parents kept it a secret from them, according to Dr. Katharine Dalke, a psychiatrist at Penn State Health who specializes in LGBTQ and intersex populations. For many, she said, this sent a message that there was something “fundamentally wrong” with who they are, and that they “weren’t lovable otherwise.”

Parents struggle with surgery decisions

While some medical professionals are beginning to take a more nuanced and affirming approach to intersex care, the decision to perform early surgery remains in the hands of parents, who vary widely in their attitudes toward sex and gender. And many struggle to cope with the challenges of raising a child with a gential difference in a world that wants to know, “Is your baby a boy or a girl?” Under this pressure, parents may feel that “doing nothing equals doing harm,” according to Stred.

However, doctors say more parents are deciding to delay surgery, though it’s unclear how common this is. Those who make this choice often navigate a difficult journey alone, with few support groups or resources to guide them.

NBC News spoke to the father of a 6-year-old girl with CAH, who requested that his name not be published to protect his daughter’s privacy. So far, she identifies as a girl, though she is gender-nonconforming, and has had no issues with urinary tract infections, he said.

While he wants her to have “autonomy in determining her own identity,” he also said he worries she will resent him for not getting the surgery. He said he would let her get the surgery when she is old enough to decide.

“My fear is that she will want to do the surgery because of social pressure or peer pressure, and doing something simply to conform or avoid being different, I would have a harder time supporting,” he explained.

Dalke said that helping kids with genital differences begins with understanding “there’s nothing inherently pathological about” them, and that with help from parents and mental health providers, they can learn how to cope with bullying and even thrive.

For this reason, intersex advocates have fought for better education and psychological support for parents, and some lawmakers have begun to listen. That was the case this year when the New York City Council passed a bill that requires the city’s health department to provide intersex-inclusive education to parents and doctors.

There are hospitals that already provide psychological counseling for parents of intersex children, and some parents still struggle in spite of it. Recalling one mother who body-shamed her child during visits, Drzewiecki said children raised in nonaffirming environments are susceptible to psychological harm. And while it’s ideal to raise these children in an affirming way, she said, it’s “unrealistic” to expect that of “everybody in our society right now.”

As for Brown-King, they said surgery did not spare them from bullying, nor are they “worried about finding love” over the way they look. When asked whether those with CAH should be excluded from surgical delays, they posed a different question: “Why aren’t we having conversations with our children about the different ways to have a body?”

“There’s no such thing as having a clitoris that’s too large,” Brown-King said. “In the same way that penises come in all different shapes and sizes, so do clitorises. Why can’t we start to push that narrative instead?”