Page-Turning Thrillers, Bath Haus and Yes, Daddy, Expose Power Dynamics Between Gay Men

With their suggestive titles and gorgeous, pink-suffused covers, P. J. Vernon’s Bath Haus and Jonathan Parks-Ramage’s Yes, Daddy seem like frothy beach reads—and, to a certain degree, they are. But woven into twisting plots, shocking scenarios, and lush settings lies a deeper, more disturbing concern: how trauma experienced by young gay men can propel them into unhealthy, even dangerous, adult romantic relationships.

In Bath Haus, recovering addict Oliver Park from rural Indiana has everything that should make him happy: his partner, Nathan, a handsome, attentive, and wealthy trauma surgeon; a sprawling townhouse in Washington, DC; and, most importantly, his sobriety. Why, then, in the opening pages, is he going to a local gay bathhouse for anonymous sex? When he follows a stranger into a private room, everything goes horribly wrong, and he barely escapes with his life. He has crossed a forbidden line and cheated on Nathan. His choices have nightmarish consequences, and his desire to keep his transgression from his partner leads him deeper into dangers both from outside and, due to his slowly crumbling sobriety, from within. The questions linger: Why risk destroying a good thing? Is it a good thing after all?

What makes Bath Haus so engaging is that Vernon gives Oliver many layers. He’s not superficial or hedonistic or merely foolish. You can’t write him off. Trauma clouds his past, including a “bad boy” ex-boyfriend and an abusive father, and confusion fills his present—does Nathan love him or want to control him? Does he need that stability, or is it suffocating? As the screws continue to turn in the story, Oliver journeys through hell, navigating a vicious psychopath, Nathan’s manipulative mother, rampant snobbery from family and friends, and his own self-destructive impulses. Vernon knows how to grab you from the first line and not let go; he also knows that plot means nothing without a character we can root for, even when he’s making terrifyingly dangerous choices.

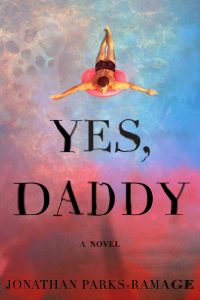

Like Bath Haus, Yes, Daddy is the story of another twenty-something gay man seeking financial security and, in this case, career advancement. Jonah Keller moved to New York City to ignite his playwriting career but has ended up waiting tables at a dead-end job. In the mode of Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, Jonah ingratiates himself with an older Pulitzer-prize winning playwright, Richard Shriver, and manipulates himself into the older man’s bedroom, but the power dynamic quickly turns. When Richard takes Jonah out to his vast and austere compound in the Hamptons, Jonah is confronted with Richard’s staff of zombie-like young men—all buff and beautiful, like something from a gay Stepford Wives. In addition, Richard’s high-toned social group smirk and leer at Jonah, reminding him of his place, testing him, and gradually hinting at their much darker intentions.

Parks-Ramage suffuses his narrative with a rich atmosphere, somewhere between the Gothic and The Great Gatsby, all while horrors await Jonah just under the surface of his lover’s lavish estate. Early on, you sense that this book may be a morality tale, a Faustian bargain about trading freedom (artistic and otherwise) for wealth. But what it becomes is more disturbing and difficult to parse. It takes its main character through a nightmare of controlling personalities, drugs, and sexual violence. Unlike Tom Ripley, whose cleverness causes us to align with him despite his amorality, we sympathize with Jonah because horrible things happen to him far beyond anything he may deserve for his earlier manipulations. Also, unlike with Ripley, we are given a layered backstory about Jonah’s homophobic religious parents and brutal experience with conversion therapy, eventually helping us to understand why he was drawn into danger and what he must do to heal from his experience.

The glossy “summer-read” marketing for these books tells only part of the story. As you read, the pages fly by—the writing is very good—but these writers have more on their minds than sheer entertainment. In each, we have an indictment of the wealth and status-obsessed circles of some urbanite gay men. This culture’s drug-infused superficiality belies a darker truth that gay men can—and do—prey on each other as a means of establishing and maintaining control; this particularly applies to the young men in these novels whose traumas have made them vulnerable. Gay culture isn’t immune from the damaging patriarchal systems that all too often govern straight culture.