6 Poetry Books That Call Us Into Community

Since the events of January 6th, I have been struggling with how to respond. What should engaged citizens and residents do when democracy is under attack, particularly amid a global pandemic? Perhaps I have been struggling since quarantine began in March and April of 2020. Maybe I have been struggling since the election in November of 2016. Perhaps even longer. It is hard to pinpoint when the struggle began. Maybe you, too, have been feeling similarly? Through these struggles, I have been reading, particularly poetry. Recent books remind of one powerful aspect of poetry by queer and lesbian women: the call to community. These are some reflections.

I.

Ellen Bass’s newest poetry collection, Indigo, arrived nearly a year ago. I have been savoring it. Bass’s work continues to deepen in its power. She expresses complex experiences in the world with beauty and joy. In Indigo, ample poems are quintessentially Bass; her poems demonstrate the power of lesbian sexuality and exuberantly celebrate life in the body, richly observed, deeply felt, joyful even—or especially—as the body ages.

Bass’s poems accumulate power because she is as willing to explore emotions with more negative valences with the same wonder and appreciation as positive. Poems in Indigo explore failure, loss, and despair with vivid clarity. For example, Bass describes her “first / entrance into the land of failure” as a “country / I would visit so often / it would begin to feel like home.” In a litany of regrets in the poem, “Pearls,” Bass beings “I’m sorry I didn’t buy my father the cashmere sweater with suede trim the summer / I went to Europe. And I’m sorry I didn’t stay longer with my mother when he died.” Each regret invites readers to understand how the speaker has disappointed people, causes, the beloved one; each regret a reminder of the vital web of shared life, finally concluding, “Forgive me, the sun will burn out. / I can’t hear your heart beating in the silence between us.” One remedy: listen more closely, more intensely, to the sound of a beating heart. Bass calls readers to the intimate and vital pulse of life. I understand it as a call to community.

The gesture is not only in Indigo; it marks Bass’s entire career. It can be easy to forget the scope of Ellen Bass’s work and linger only on the four collections of published poetry: Mules of Love, The Human Line, Like a Beggar, and now Indigo. There is so much pleasure to experience in these books, but they are only a part of her public poetic work. In 1973, with Florence Howe, the founder and publisher of The Feminist Press, Bass edited No More Masks an anthology of poetry by women; it galvanized poetry as an art form of the women’s liberation movement. In the 1980s, with Laura Davis, Bass published The Courage to Heal, another transformative book about recovery from sexual abuse. It is not too bold to assert that the #MeToo movement could not exist without Ellen Bass and Laura Davis’s work—along with the work of many thousands of feminists naming sexual violence. In The Courage to Heal, Bass and Davis named the problem and, just as importantly, provided a path for recovery. I posit that The Courage to Heal—the book itself and public engagements with it—is a poem. It is a language that transforms readers’ understanding and lives in the world. Considering these two books, The Courage to Heal and No More Masks, in combination with her own poems, Bass is one of the most influential public poets today. The break-through of inaugural poet Amanda Gorman reminds us of the power of poetry in public life. Public poets occupy spaces such as inaugural poets or city and state poet laureateships; some public poets like Mary Oliver and Rupi Kaur are best-seller authors. All of these public roles are vital. Ellen Bass is another type of public poet: a poet who is a transformative thinker and writer in the world, a poet who brings new formations into being, a poet who convenes and conjures vibrant communities.

II.

Bass’s work extends five decades, fifty years of community-making. Kelly Rose Pflug-Back’s work is just beginning. Her impressive debut collection, The Hammer of Witches, uses magic and mythology as central metaphors to conjure the communal. Pflug-Back draws on an eclectic array of mythology—in one poem alone alluding to the Vedas and the Edda—as well as the practice of witchcraft to highlight the magical and mysterious of contemporary life.

“We were witches once, you and I,” Pflug-Back asserts in the opening poem, “Malleus Maleficarum.” This artful poem blends the history of woman/witch hating with contemporary lesbian life, confiding “your love is a heathen ritual” then concluding, “the two of us lost together / still / / in this forest / of tall buildings.” Rich history combined with current imaginative practices is a defining characteristic of this collection.

In “After the Fall,” Pflug-Back writes,

every vast and ancient magic

that this world of men has killed

and pined foralive somewhere

just out of site

The conclusion is an ars poetica:

Outside the realm of clumsy words

there are no such things as endings

only new things made from the old.

Like many religions, witchcraft is communal, practiced in covens. Part of its spiritual and material work is providing human explanations for the inexplicable, magical as well as painful. Pflug-Back’s poems evoke magic as in “Grimoire” or the delightful “Hepatomancy,” a practice of divination from entrails. They also recognize communal gatherings as a vital part of magic. In “Hepatomancy,” Pflug-Back writes,

I am sewn together

from the flesh of many

and we ache.

Human life is both constituted by others and sharing in the pain of others. Elsewhere, Pflug-Back mines magic in human relationships. “For Dave” begins:

The day after you died

my son asked me to draw a picture of you

holding a blue balloon.

This lamentation concludes,

And now here I am wishing

I could have found and afternoon somehowto take that trip across town

and show up at your door

with a big blue balloon

while you were still alive.

Perhaps unknown to the Pflug-Back, “For Dave” echoes Maureen Seaton’s stunning poem “White Balloon” demonstrating a generational shift but the endurance of lesbian lyrical poetry. United by the image of a balloon, white for Seaton, blue for Pflug-Back, these poems also document the material changes of queer lives. Seaton’s poem emerges from a communal memorial for people who died from AIDS; Pflug-Back’s is a domestic scene with a child. Both poems call readers into a community for mourning. Seaton laments “the ease with which we love”; Pflug-Back wishes for more time with beloved friends. Both poems call us to community.

III.

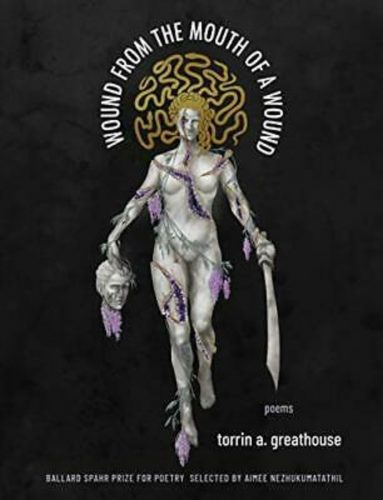

torrin a. greathouse’s new collection Wound from the Mouth of a Wound, selected by Aimee Nezhukumatathil for the Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry, is in a dynamic conversation with Pflug-Back’s collection. greathouse’s opening poem, “Medusa with the Head of Perseus” introduces many of the themes of this collection: disability, body dysmorphia, rape. It also artfully demonstrates greathouse’s proficiency with language and her energetic ability to transform images in service to her story.

Many will read Wound from the Mouth of a Wound with admiration for the way that it brings language and visibility to trans experiences and the realities of living with disabilities. greathouse and this collection join vibrant conversations in contemporary poetry communities on trans identities and living with disabilities. I appreciate both of these elements and particularly the way greathouse calls readers into a community that values trans people and people with disabilities.

“Weeds” demonstrates greathouse’s extraordinary poetic power. With short lines and stanzas between four and six lines, greathouse establishes the “shower stall” as the “body’s confessional” where she admits, “I love / most what can be / removed from me.” She builds an extended metaphor between unwanted parts of the body and weeds with a moving meditation on weed removal as “women’s work.” She writes, “Nothing’s more / femme than empty / / field, a place to bury / seed.” The poem concludes with the voice of the weeds:

We were your first teachers.

Even in the harshest season,

we survive. We bloom forever

where we are told we don’t belong.

This poem reworks communal formations in meaningful ways, echoing feminist insights from the 1970s with contemporary trans sensibilities, making vibrant connections between human bodies and nature, and calling readers into the collective first-person plural with weeds. We were your first teachers. We survive. We bloom. This vision of community is one that leaves me awed.

IV.

Theorem, Elizabeth Bradfield’s newest collaboration, is a departure from her earlier work. Created with artist Antonia Contro, Theoremcounterpoints the words of Bradfield with the art of Contro. While Bradfield’s previous books establish her as a naturalist concerned with human-created conditions on the natural world, Theorem looks to mathematics, particularly geometry, as a tool to refract her childhood experiences. Bradfield writes:

There were five of us. And a dog.

Only one dog at a time.No one else.

The results are fractal

The trajectories radiate.

The combination of Bradfield’s words with Contro’s art demonstrates the energy of collaborative enterprises; each element opens meanings for the other. In the afterword, they describe their collaboration as “words and image influencing, pushing, urging, questioning each other. Artist and writer finding new ways to articulate what is embedded in what they create.” In addition to inspiring more collaborations between artists, Theorem is a physical manifestation of community, a community of a singular poet and artist, but, by extension, in an invitation into communities of poets and artists.

V.

Amid this reading of new work by lesbian and queer women poets, I returned to the work of Chrystos and spent weeks marveling at the corpus of her work. If I had more time and could really stretch out to tell you everything, I would write a detailed, sustained meditation on the poetry of Chrystos. Maybe it will come. Right now, I want to note that echoes of Chrystos’s work are in all of these collections. Chrystos’s work is filled with gorgeous, vexing, challenging, inspiring images of bodies and nature. She breaks conventions of contemporary poetry just because she can, because she has so much control over language, images, and the line, that she wants to flaunt her power. It is heady. It is exciting. It is worth your consideration as a reader, as a human, longing, hungering for some meaning, for connections in our troubled world. Chrystos knows about community and connection, and she wants them. She wants us to have them.

VI.

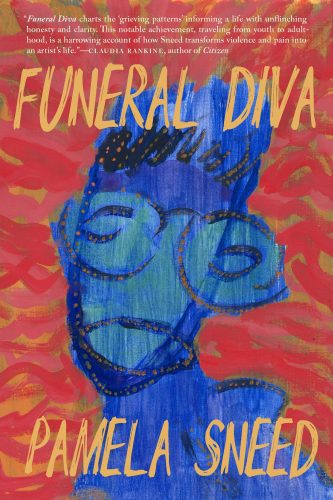

Funeral Diva, the new collection by Pamela Sneed, joins this gathering of new poetry that powerfully calls readers into community. While Sneed fashions herself as a diva in the title, in fact, these poems demonstrate rich community engagements that belie the temperament diva implies. The work in this collection—a hybrid of poetry and prose—calls a range of people, living and dead, into a community invoking a history of queer Black writers and insisting on a powerful present and future for Black queer writing.

Like the hybrid work that characterized lesbian-feminist writing in the 1980s and 1990s, Funeral Diva is a mix of poetry and essay braided together to illuminate how the two genres intersect, co-exist, merge, hybridize. Reading Funeral Diva amid COVID-19 as it harkens back to another, different epidemic, AIDS, is a powerful reminder of the responses of queer communities during the 1980s and 1990s. Sneed writes,

when I saw the poster silence equals death in the windows

of the Leslie Lohman Museum

That pink triangle on black paper

from blocks away

It called to me like a beacon

Amidst societal madness/personal struggles and the Trump presidency

to never give up

It reminded me too of a generation of gay and lesbian warriors who are no

longer here with us

felled to AIDS and cancer

But on their deathbeds used the mantra to inspire

Silence=Death

I think about when Black gay and Latinx poets Essex Hemphill

Donald Woods

Don Reid

Roy Gonsalves

Rory Buchanan

David Frechette

Craig Harris

Alan Williams and Assotto Saint and so many more were still here

How their black hair began to sprout twists and knots go wild and kinky

to signify early Black gay consciousness

I think about when I first met Donald Woods outside of a bookstore

in the West Village called A Different Light and we fell in love

We were all so young Black awkward and gangly but fierce and

determined.

Funeral Diva fueled my desire to return not only to the poems of Chrystos, but also the poems of Dorothy Allison, Minnie Bruce Pratt, and many other writers that I read thirty, thirty-five years ago when I was coming out. Sneed is an inheritor to the vibrant poetic traditions of lesbian-feminism and the Black gay and lesbian renaissance of the 1980s. Funeral Diva is her love letter to the people and work who created her. Sneed, like the other poets here, calls us into community with all of its challenges, its foibles its uncertainties. As she tells us in her conclusion to Funeral Diva,

And then I understand what it all means

If we can survive

have equipment means money

support conditions

There are also other possibilities

We can heal.

Indigo by Ellen Bass Copper Canyon Press Paperback, 9781556595752, 64 pp. April 2020 The Hammer of Witches by Kelly Rose Pflug-Back Caitlin Press Paperback, 9781773860299, 72 pp. March 2021 Wound From the Mouth of a Wound by torrin a. greathouse Milkweed Editions Paperback, 9781571315274, 88 pp. December 2020 Theorem by Elizabeth Bradfield Potry Northwest Editions Paperback, 9781949166026, 96 pp. November 2020 Fire Power by Chrystos Press Gang Publishers Paperback, 9780889740471, 131 pp. October 1995 Funeral Diva by Pamela Sneed City Lights Books Paperback, 9780872868113, 160 pp. October 2020