Reflections on Black Gay Literature

In Conversation: Gar McVey-Russell & Philip Robinson

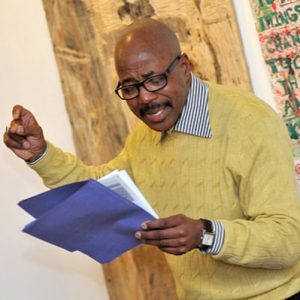

Philip Robinson is an award-winning poet, writer and activist. His writing of poetry spans forty-nine years. Robinson is anthologized in several gay/queer literature’s front-runners: In The Life, A Black Gay Anthology, The Road Before Us: 100 Gay Black Poets, The Last Closet: real lives of lesbian and gay teachers, and When The Drama Club is Not Enough.

Philip Robinson also has two of his own books of poetry, We Still Leave a Legacy and in The Trenches The Voice of A Guidance Counselor. Philip is a long-term volunteer @ AIDS Action Committee (AAC) of Massachusetts on their Bayard Rustin Community Breakfast Committee. This iconic event will celebrate its 30th year in 2019.

Gar McVey-Russell is a writer based in Oakland. His work has appeared in Sojourner: Black Gay Voices in the Ages of AIDS and Harrington’s Gay Men Fiction Quarterly. Gar also writes a blog, the gar spot: fiction and musings from a black gay writer with delusions above his station. His first novel Sin Against the Race was published in October, 2017.

Philip Robinson and Gar McVey-Russell both began writing in the 1980s, Philip poetry, Gar fiction. Their writing spans from the beginning of the AIDS epidemic and the Black Gay arts movement to the age of RuPaul’s Drag Race, and greater visibility of black queer folks from the entire spectrum of gender and sexual identity. In this discussion, both writers discuss their beginnings, influences, and where their writing stands today.

Gar: Philip, your writing dates back to the 1980s, a period of great significance for Black Gay literature. I came out in the late 80s, so your voice was among those that provided me a safe space in which to explore my sexuality. What can you tell me about that time? Who influenced you and guided you in your writing?

Philip: I had the distinct honor to have met and become close and dear friends with two extraordinary writers, the late Thomas Grimes (Milking Black Bull: 10 Gay Black Poets, Poets on the Horizon) and author of numerous plays and the late Roy Gonsalves (PERVERSION and Other Countries: Black Gay Voices). These two individuals, soul-mates as well, changed my life through their love of the written word and ammunition of love in their delivery.

My literary “girlfriend” the late Joseph Beam took twenty-nine of us black gay writers and put us into a literary first, In The Life: A Black Gay Anthology. The outgrowth of this book came about because Beam felt a frustration with gay literature that had no message for and little mention of Black gay men. “The bottom line” he wrote, “is this: We Black gay men who are proudly gay. What we offer is our lives, our love, our visions.…We are coming home with our heads held up high.”

So Gar, is there a particular audience you are trying to capture through your writing?

Gar: I write stories that I would have wanted to read in my late teens or early 20s, when I was struggling with my sexual orientation. I didn’t read any gay fiction growing up. I think I was too scared to go there. But I was hungry for it. In Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison—a book that has stayed with me for decades—he includes a brief passage about gay nurses at the teaching hospital at the protagonist’s black college, and the secret lives that they live. Honey, I must have read that passage a half-dozen times! Sadly, the gay nurses never came up again. So I hope my writing will speak to others who are dealing or have dealt with issues of race and sexuality.

At the same time, I’m still naive enough to think that everyone, regardless of background, will want to read it, should read it. Case in point, a reader who identified herself as a straight white woman wrote a very lovely review of my novel on Good Reads. She wrote that she could identify with my story easily, because it deals with belonging. I think it’s important for all of us to find each other’s humanity. Really, it’s the only way in which humanity will survive.

Philip you have written a lot about the AIDS epidemic. How challenging is it to write about all whom you’re lost to AIDS? Has time permitted you the ability to do so?

Philip: In the beginning stages of this pandemic known as HIV/AIDS, I, like many others were at a precipice. It felt like I had been taken to the end of a long deserted road with no directions as to where to turn. I couldn’t begin to grasped the magnitude of personal friends I knew who had contacted the virus. I almost felt like I was witnessing a tremendous encroachment in my space, our sacred world, known as a community. People in rapid succession were being taken to the hospital, seen by doctors who themselves were confronted with this medical uncertainty, and in so many cases, these same folks were dead within months of their diagnosis.

In the late 1980s, I took the opportunity to channel my frustration, the intense pain, unanswered questions by volunteering at the AIDS Action Committee (AAC) of Massachusetts. I had heard about this new organization founded by Larry Kessler that was attempting to find ways to help us who were thirsty for information. Somewhere in that pursuit I was hoping to hear that this sudden departure from our norm, was an aberration of sorts.

Long-time social activist, and staff member at AIDS Action Committee, Harold DuFour-Anderson, presented a great concept to the AAC staff to start an annual Breakfast honoring the principles of the legendary black gay community organizer of his time, the late Bayard Rustin. In its design, the Bayard Rustin Community Breakfast (BRCB) was created to recognize the roles of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people from communities of color in the fight against AIDS epidemic.

As a writer, I often siege the opportunity to write about the insurmountable pain that surrounds me. The AIDS epidemic became that unspeakable malaise. There was this vulnerable cloud that casted a mask over us. So, I wrote to escape the suffering. I wrote about people I had met through our monthly readings together.

So, in my need to find solace, in 1988, I wrote this poem, We Still Leave a Legacy. In this particular piece I attempted to capture the dismay, a sense of silence, but also a degree of hope and determination. I needed to believe no one’s life is in vain. I firmly understood that yes, people die, but their legacies will live on. This was one way to cope with the vast loss. It was clear to me we needed to pay homage to those who came before us. In a spiritual way, we created our sense of hope, to diminish the fear.

What influenced you to write your new book, Sin Against the Race? What are some of the themes that are pronounced in this piece of work?

Gar: I just went to a screening of Tongues Untied recently at Oakland’s new LGBTQ Center in the Lakeshore district. It’s been a while since I had seen it. But scene after scene, I saw parts of my book—it influenced and informed me that much. For instance, there’s a scene when Marlon talks about how he learned about his identity behind the epithets thrown at him (faggot, motherfucking coon). I have a scene where my protagonist Alfonso says, that it doesn’t matter if he’s called a nigger or a faggot, the pain is the same.

So one of the major themes of the work deals with homophobia in the black community. It took me a while to realize that this is where I wanted to go. I needed to time to find that voice and give it permission to speak. I felt like I had to fight some internal barriers—there’s a strong sense in the community about not airing our dirty laundry. As the story evolved, and became, I think, more nuanced, then I felt better about this theme being my center. One thing I ended up doing is tackling the issue inter-generationally. So we see instances of homophobic tendencies in Alfonso’s father and grandfather, two political icons lionized by the larger community. We also see folks Alfonso’s age, Leon and his love interest Jameel, maintain a homophobic front to “keep it real.”

Those of us who are black and queer still live behind two veils sometimes, and we encounter a lot of the problems W.E.B. DuBois discussed over a century ago to this day. I’d say the difference now is that we’re a little less invisible than we used to be. That’s cause for hope.