Migrant Caravans Spark Concern Among El Salvador LGBTI Groups

A group of men, women and children with their backpacks and other things they needed for a long trip left Plaza del Divino Salvador del Mundo in the Salvadoran capital at around 8 a.m. on Oct. 28.

They were part of a caravan that formed with the ultimate goal of reaching the U.S. The Salvadoran government has asked people not to risk their lives on such a trip, but more than 300 people decided to ignore this plea and replicate the caravan of Hondurans that left the city of San Pedro Sula on Oct. 13.

“Stand with the people who will participate in this caravan. Let people know where you are so others know,” reads a message that was published on a Facebook page on Oct. 24. “It is easier for everyone to arrive in groups.”

“There are people from across the country,” it says. “El Salvador emigrates for a better future.”

This page was created on Oct. 16, and it is administered by a person who has not identified themselves. The page encourages people who want to leave the country to create and join groups on social media to find out about groups in their areas that would travel with the caravan.

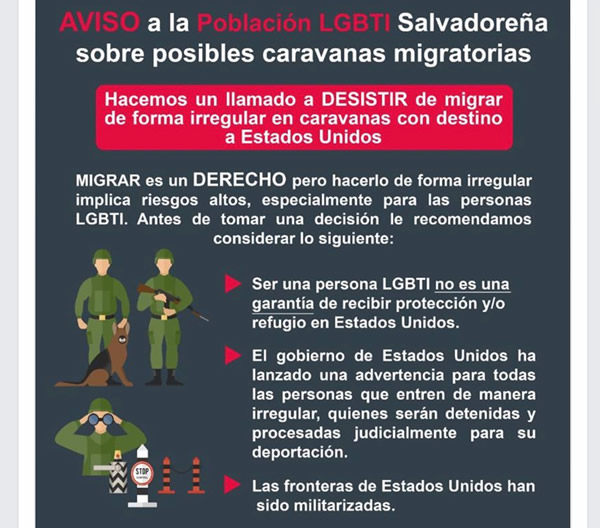

This situation has sparked concern among different activists and civil society groups, including LGBTI organizations that are part of the LGBTI Salvadoran Federation. COMCAVIS Trans, a transgender advocacy group, published an advisory that warns members of the LGBTI community not to migrate.

“TO MIGRATE is a RIGHT, but doing it in an illegal way carries high risks, especially for LGBTI people,” says the COMCAVIS Trans advisory that it posted to its Facebook page.

“Some LGBTI people migrate to improve their economic conditions, since in El Salvador many LGBTI people, especially transgender women, face clear discrimination in employment,” COMCAVIS Trans Executive Director Bianca Rodríguez told the Washington Blade. “There is a lot of concern over their personal safety, gangs who target them, cruel treatment and abuse of power on the part of police officers and soldiers.”

The advisory, among other things, mentions an LGBTI person should not expect to receive refuge in the U.S. because of their sexual orientation or gender identity. It also emphasizes the U.S. government has said anyone who enters the country illegally will be detained and be processed for deportation.

Liduvina Magarin, vice minister of El Salvador’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, declared the government would provide “escorts” to the group of Salvadoran migrants with the sole purpose of keeping families informed so they make responsible decisions and not put the lives of children at risk on the migratory route.

But another group of people gathered at Plaza del Divino Salvador del Mundo on Oct. 31 to form a second caravan with the same goal of seeking a better future for their families.

“If it is normally dangerous for us in our daily lives, this risk triples in the caravans,” Aldo Peña of Hombres Trans HT, an advocacy group for trans men, told the Blade. “Not only are they violated or will be violated at the borders by the authorities or become victims of crimes, but they will also be victimized by those who are part of the caravans.

“I would not go to possibly die on the road,” added Peña. “They (migrants) must remember that their families will continue to experience the injustices of this country if they leave.”

A Salvadoran trans advocacy group has issued this advisory that urges LGBTI Salvadorans not to join migrant caravans to the U.S.

Camila Portillo, a trans activist, for her part told the Blade that “we must not stop the dream of emigrating for a better future, if, for example, the government and the country does not guarantee socio-economic development for the LGBTI community.”

“In practice, it is not carried out in the correct way, although there are people in power who tend to support LGBTI people,” she said.

“Here there is a lot of forced internal displacement because of the issue of violence, so I don’t think it’s a trend,” Portillo added. “It’s mostly a structural issue that the government does not guarantee safety not only the LGBTI community, but the population in general, but it is an at-risk population that is more vulnerable and the government therefore must guarantee the welfare of the people.”

Portillo remains hopeful the migrants will have the help they need and be able to fulfill their objectives without many obstacles in the countries through which the caravans pass. She also urged the Salvadoran government to begin to tackle corruption within its institutions, to enforce decrees and different guidelines that have been created in support of the LGBTI community and to make sure it implements them as opposed to simply have them in writing.

“Given the high rates of violence in El Salvador, many of the people who make up that caravan will have their own reasons for migrating,” said Rodríguez. “But the Salvadoran government in this situation should at least coordinate with national institutions, international associations and bodies to provide some protection (to them) along the route and urge countries through which they travel to reach the U.S. (Guatemala, Mexico) protect their human rights.”

Articles 13 and 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights says people have the right to move freely, including seeking refuge and asylum in extreme cases where their life is in danger.

People with the first caravan had reached Mexican territory as of deadline and families provided them shelter in which they were allowed to remain together. They also received medical assistance, food and access to baths and showers.