Judith Katz and Hilary Zaid on Inheritance, Influence, and the State of the 21st Century Lesbian Novel

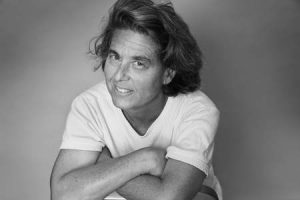

Judith Katz is the author of two published novels, The Escape Artist and Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound, which won the 1992 Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Fiction and has been reissued in its 25th anniversary edition by Bywater Books.

A 2017 Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, Hilary Zaid is the author of numerous works of short fiction, including “My Triple X Valentine’s at the Far Point Senior Villas” (Day One) and the Pushcart-nominated “For Non-Speakers of the Mother Tongue” (The Tahoma Review). Her debut novel, Paper is White, was released in March from Bywater Books.

Hilary Zaid: Judith, your novel first arrived on the literary scene 25 years ago. Can you say something about what your literary influences were at that time, and how you wrote your way into that literary landscape?

Judith Katz: In the 80s when I was deep into Running Fiercely, I was writing to make a place for lesbian characters who were Jewish daughters who didn’t stay home—in other words, I was writing to make images of Jewish women who were like me and people I knew, but also (I hoped) against stereotypes. At the same time, one of the most vilified characters in Jewish American literature in the late 1960s was Sophie Portnoy, Philip Roth’s stereotype to end all stereotypes of Jewish mothers in Portnoy’s Complaint. A whole genre of feminist literary criticism began with the vilification of this character and the man who created her, and halfway through the first solid draft of Running Fiercely… here I was creating Fay Morningstar, Nadine and Jane’s monstrous mother—not nurturing and overbearing as Sophie Portnoy, but overbearing and enraged. Ellen’s mother, Marilyn, on the other hand, is (to my reading) more subtly enraged but withholding. Both mothers are entirely self-involved and yet, look at the amazing lesbian daughters they have produced—because of or in spite of themselves. I am very interested in how Marilyn wants her daughters to be Jewish but not too Jewish. Fay, on the other hand, acts out her Jewishness ferociously and unconsciously, and while a climax of Running Fiercely… takes place in the middle of a Jewish wedding, it’s never spoken of as such.

Nadine and her sister Jane live in a mythical town where both Jewishness and lesbianism are part of the fabric of their everyday lives. [In your lastest novel] Ellen Margolis, on the other hand, is copiously and consciously planning a Jewish wedding. She and her partner work for Jewish organizations set in a secular world. What has shifted there?

Hilary Zaid: Ellen and Francine, living in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1990s come to their lives out of a tradition of queer activism rooted in Queer Nation and leading to the marriage equality fight that will come in their wake.

In Paper Is White, Ellen is also seeking a connection to her cultural inheritance, planning a Jewish wedding at a time when neither Judaism nor the larger culture recognizes her place in that tradition. And she seeks her blessings from the past, reaching back to the generation of her grandparents to find a way that she can belong.

In Far From the Tree, Andrew Solomon writes about the difference between vertical and horizontal identities, which is the difference between identities we share with our parents and those we don’t. LGBTQ+ identities are perfect examples of horizontal identities, because we typically come from straight families, and they have the potential to put us into conflict with our other, vertical identity. That’s one thing both of our characters are trying to identify for themselves: the point at which the vertical and horizontal axis intersect.

So Judith, how did the question of belonging shape your characters and their story? It seems that, in your two sisters—Jane and Nadine—you’re tackling this question from two different angles.

Judith Katz: Jane reacts to the worlds around her by at least trying to behave and doing what she’s asked (e.g. she wears a fancy gown and actively participates in her oldest sister’s wedding) which puts her relationship to her lesbian lover at risk. She’s the family member who is constantly juggling family duty and community responsibility. Nadine on the other hand just acts–sets her hair on fire, hides in the holy ark, disappears into some mythical Jewish history (by the way, this part of the book delights some readers and drives others to distraction), then returns to her family only to be asked to leave. I was very much influenced here by a scene in a silent Yiddish film I saw in the 1970s while this book was cooking, that was based on the Shalom Aleichem stories, Tevye and His Daughters (which evolved into the musical Fiddler on the Roof), where the daughter who marries a gentile is locked out of the family home and forced to watch her ailing mother die through a rain drenched window. That was one of the starting images I brought with me as I made this story. Nadine is that daughter but in many ways, Jane is too.

For much of 20th century gay and lesbian literature, the big plot problem was the risk of coming out of the closet. Neither of our novels is a coming out novel. But Paper Is White is a novel about secrets. Ellen has a lot of them, and the book begins with an important one–someone has phoned and she isn’t sure who it is but she doesn’t share this or her ensuing relationship with the caller with her partner and future wife. Tell me about those choices.

Hilary Zaid: Yes—just because our characters are not coming out of the closet doesn’t mean that we haven’t inherited the question of the closet as a literary trope. For Paper Is White, the entire novel really is about the quest to understand: how much should we tell each other?

Ellen is a Queer Nation dyke who came up in the great age of coming out on college campuses, the defeat of ROTC campus recruiting, into a queer world set on fire by outing, a new, loud queer generation coming into its own. That’s the framework in which she’s constructed her queer identity–very far from her childhood home.

When Ellen and her girlfriend Francine decide to get married, though, she’s suddenly faced with the prospect of having to fit her independently forget queer self into relationship with her family and its traditions. I think it’s a mark of a generational shift between our two novels that she’s not contented with being a person outside the window. But for Ellen, who learned circumspection from her grandmother and who needed to keep her cards close as a queer kid in a closeted time, bringing her two worlds together is not a simple negotiation.

Jewishly, the act of concealment has been a reflex of self-protection, earned over centuries of ghettoization, expulsion, pogrom, genocide. For hundreds of years, the best thing we could do was lay low. Put that together with mid-century American Jewish assimilation and the impulse of so many Holocaust survivors who came to this country to keep silent about their experiences as a means of survival and you’ve got a very powerful cloak of silence to contend with.

Paper Is White is all about facing the legacy of that silence. The title comes from a traditional Jewish lullaby, and when I encountered it several years into writing the book, I knew instantly that it was the novel’s title: the color of paper on which no words are written. That’s not an absence. It’s a palpable omission, and that’s what Ellen is trying to apprehend.

Judith, I wonder if a paper on which no words are written is not in some ways like a “high, thin sound.” Can you tell me more about your title?

Judith Katz: I had a number of working titles for Running Fiercely… over the years it took me to make this book: The Monster in My Mother’s House; The 41 Laments; and my personal favorite, The Vildachia Of New Chelm (which my publisher, Nancy K. Bereano rejected immediately). On my original contract with Firebrand it was known as Untitled Novel by Judith Katz. Then, one day, a few days after I returned from my first Escape Artist research trip to Buenos Aires, I was sitting alone in my favorite Chinese restaurant when it just appeared to me: Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound… because that is what Nadine is doing. The high thin sound is God I think… isn’t that how God spoke to Moses, via the burning bush? So even though Nadine is seen running away, she is also running toward–maybe not God as we understand or don’t understand God (or believe in God) but something like God? A Jewish God? Not sure. The characters in my book live in an entirely Jewish world but remember, Jane, Rose and Nadine live in a spiritual world guided by Tarot cards, dreams, and magic–God back in those lesbian olden days was a Goddess or Goddesses. Nadine finds her Jewish life through ritual and genetic memory, which she likely inherited (much like the violin) from her mother’s side of the family. Ellen and her bride to be in your book are re-appropriating the Jewish wedding ritual to reflect their own values and community as lesbians. Nadine is literally swimming through her past in order to understand where she belongs.

Hilary Zaid: “Swimming through the past to find out where she belongs”–that’s a good description of queer literature’s relationship to the canon, where it has always lived, but often in the closet—especially literature about women.

To be a queer writer is to stand in relation to two sometimes overlapping, sometimes diverging traditions, and stake out ground, to say with Adrienne Rich, “I choose to walk here. And to draw this circle.”

I think you and I both know that the places in the canon in which a lesbian literature can be said to exist are fewer and farther between than they are for gay men, and it’s a lot harder, still, for lesbian voices writing lesbian lives to find their way into the mainstream. In the 90s, when your novel came out, we were still living in the heyday of the independent, lesbian feminist presses. We’ve lost something in losing so many of them. I hope we’ll see an efflorescence of women’s presses of all types, as we’ve been seeing the small press in general come back. But I hope we’ll continue to push the envelope on what is possible for us within the mainstream. Based on some informal statistics gathered from anecdotal observation and from Lambda Literary, the number of books published between 2011 and 2016 in the mainstream presses that feature significant lesbian characters is fewer than 12. That’s within a five-year span. And two of those were written by straight men. I think the numbers tell us we have a problem here.

Greater representation in our own voices–that’s the high, thin sound toward which I’m running! What about you? What’s next for you? What are you working on now?

Judith Katz: Well, for a number of years I was working on a more realistic somewhat contemporary novel which has been in a drawer for about five years…and I have begun in earnest continuations of both Nadine’s story and the stories of Hankus and Sofia from The Escape Artist. And then I got sick with non-Hodgkins lymphoma–two different kinds within the span of three years and while I am recovered (for now) I’m still trying to get my reading and writing chops back. I’ve been doing these short little pieces which my publicist. Michele Karlsberg, has been placing in on-line journals, and those are like going to the gym–my writing muscles are coming back. But they aren’t fiction, they are a whole other kind of writing, and while I enjoy the exercise of being a smarty pants lesbian elder, I really am looking forward to diving back into characters and mythos–ie, I want to continue writing us (Jewish dykes) into literary history. I am particularly interested in the community of Jewish women composers in Holland who were resistors during World War II. Some of them had women lovers. A perfect crowd for Hankus and Sofia to fall in with, don’t you think?

What’s on the boards for you?

Hilary Zaid: I was at work for quite a long time on a project that updated Patience & Sarah, a classic of lesbian literature that was very avante garde when it was published in 1969 and which I was absolutely taken with when I first discovered it in the children’s section of my local library a few years ago. I was soldiering away at a revision of my Patience project this fall and then the election happened and brought with it this sense of tremendous futility; I couldn’t move forward with the project, which felt meaningless in the face of historical realities, and I really thought it was Trump. Finally, though, I realized that the novel was missing a key plot mechanism and it just didn’t have enough momentum to move forward. It turns out that it’s really hard to “update” some of the old, queer classics because being queer–and the dangers associated with coming out–used to be a plot and now it mostly isn’t. (Some of our most interesting lesbian writing these days is coming from writers like Chinelo Okparanta and Nicole Dennis-Benn and Lesley Nneka Arimah, who are setting stories in countries where homophobia can still work as a major plot element–which is to say that the locus of that plot has had to shift.)

Ultimately, I put that novel in the proverbial drawer for the sake of something completely different: a novel about the power of the written letter in a digital age and the problems of anonymity and privacy in the world of surveillance capitalism. Writing about the present, I’ve discovered with Paper Is White, is always fraught, because the present is always becoming the past and–as it turns out–the future can start looking a lot like the past, too!

Judith Katz: Yes, especially in this fraught political time

Hilary Zaid: But it’s a place to start.